Confessions Of A Colombian Extrajudicial Killer Commander

During Colombia's interminable battle against left-wing guerrillas, extrajudicial killings by the armed forces became the norm, according to former colonel Gabriel de Jesus Rincon.

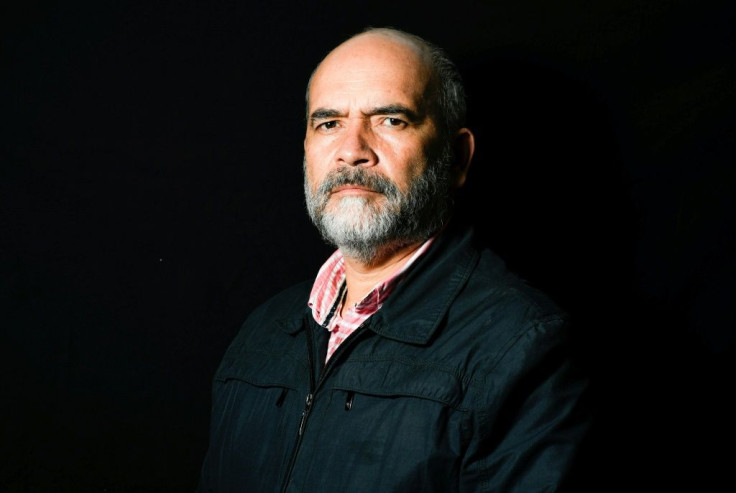

"I didn't kill them but I contributed to allowing it to happen," Rincon, 53, told AFP in an exclusive interview.

Revelations about these illicit murders caused a huge scandal in Colombia, a country scarred by six decades of violent conflict that left eight million people either dead, disappeared or displaced.

After 22 years of military service, the steely-eyed Rincon was forced into retirement, convicted of forced disappearances and murder.

Between 2006 and 2008, Rincon commanded the 15th mobile brigade in the country's east.

The offensive against rebels was so intense that the morgue in the little village of Ocana was overwhelmed in September 2008.

Fearing a health crisis, the local mayor and priest decided to transfer 25 bodies to a mass grave -- several corpses were identified as civilians that had disappeared weeks ago.

Rincon admits that he knew who the victims were when they were exhumed: youngsters from Soacha, a poor suburb of the capital Bogota some 740 kilometers (460 miles) away.

"I arranged... for them to be passed off as combat dead," he said.

It's the first time he's opened up to a media organization about his role in atrocities that have landed him in front of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) -- the justice mechanism set up following the historic 2016 peace accord between the government and the now-disarmed Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

"I didn't report it and I allowed the units stationed there, in the combat zone, to act in that way," he said.

Soldiers organized their own "body count" of killed guerrillas and drug-traffickers -- which soared under the right-wing president Alvaro Uribe (2002-2010) -- with prizes such as medals and promotions on offer.

Rincon, who has been held for 10 years, was in 2017 sentenced to 46 years in prison for the murder of five youngsters aged 20-25, subsequently passed off as "combat dead."

Two civilians, working as recruiters, brought the victims by bus to Ocana, offering them "easy money." Then they were executed by soldiers.

"I never had to explain anything to (the soldiers) ... I just told them: you're going to go on an operation, we're going to bring some people to you and you know what you have to do."

Victor Gomez was 23 when he made that one-way journey with two others.

"They got them drunk, then took them to ... a fake military check-point," said Carmenza Gomez, Victor's mother.

"The next day they were dead."

All three were presented as gang members.

"Victor had a bullet in the forehead, a coup de grace," said the 62-year-old, who is receiving protection due to threats.

Thousands of combat dead were in reality civilians killed in cold blood.

The public prosecutor has identified 2,248 of those, 60 percent of which were killed between 2006 and 2008, during the administration of Uribe, who is now a senator and who denies any responsibility.

"The commanders were encouraged to obtain results however possible, and that resulted in them committing ... these assassinations ... giving them the appearance of legality," said Rincon.

According to Jose Miguel Vivanco, from Human Rights Watch, some case files were "forgotten in the military criminal justice system" but that the United Nations' estimation of 5,000 executions was "credible."

This wasn't the fault of "a few bad apples, but generalized and systematic crimes," said Vivanco.

Investigations have been opened against 29 generals.

Rincon was once asked by General Mario Montoya, now retired and also due to appear before the JEP, what he intended to do to "contribute to the war."

He says Montoya told him: "Why don't you take some guys out of the morgue, dress them in uniforms and claim them as results."

While he never received an order to kill, Rincon says there was a "Top 10" of military units ranked according to the number of people they killed.

Montoya's lawyer insisted his client "encouraged absolutely nothing."

"There are 2,140 military linked to extrajudicial killings investigations, that's 0.9 percent of those operating in the army at that time... that shows that there was never a directive given to the army (to commit) such atrocious acts," said Andres Garzon.

Rincon has been out on bail since 2018 while awaiting his JEP trial.

The JEP has been in action in Colombia since March 2017, investigating and putting on trial former FARC guerrillas and members of the armed forces accused of serious crimes.

After asking forgiveness for his crimes, Rincon must tell the truth and compensate his victims, or their families, in order to qualify for an alternative punishment to his lengthy prison sentence.

Having escaped an assassination attempt last November, he has been put under police protection, alongside another 19 former military personnel due to appear before the JEP.

His lawyer, Tania Parra, has also been threatened.

"Retelling the truth after more than 50 years of conflict... undoubtedly implies a risk," said Giovanni Alvarez, director of the JEP's investigation and accusation unit.

Rincon is waiting to face the families of his victims, eager to explain the "instigation and pressure" that ruined so many lives, turning him into an executioner "for the profit of institutional interests."

"It's going to be very difficult to see each other face to face, victim and aggressor," he said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.