Covid Leaves Brazilian Amazon City Struggling To Breathe

The hardest thing about caring for eight relatives with Covid-19 at the same time, says Brazilian student Lais de Souza Chaves, was deciding who got oxygen.

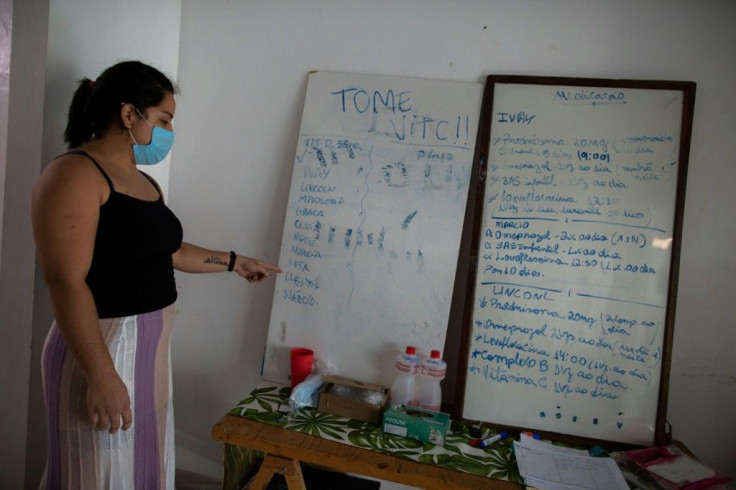

The pandemic had so overwhelmed their city, Manaus, that it ran out of hospital beds and medical oxygen -- leaving Lais, 25, and her sister Laura, 23, to set up a makeshift intensive care unit at home, with no medical training.

After joining countless others facing the same situation in a desperate hunt for oxygen, they would rotate their precious supply to whoever seemed most in danger of asphyxiating to death.

Learning as they went to install airflow regulators, tubes and gauges, the sisters would switch the oxygen supply without telling their relatives, to avoid making the situation worse, they said.

"I have a panic attack if someone says the word oxygen. My whole body shudders," Lais told AFP.

For several weeks in April and May last year, and again in January and February this year, Manaus became the horror story that health experts and political leaders around the world warn about when they urge people to stick to lockdowns, face masks and social distancing.

The northern city, known as the unofficial capital of the Amazon rainforest, was hit so hard by the surge of Covid-19 that it had to resort to mass graves and refrigerated trucks to deal with the overflow cadavers.

The first wave was so bad some researchers hypothesized when it tapered that the city of 2.2 million people had reached herd immunity.

Then the second wave hit, and shattered that hope.

Researchers now suspect the resurgence in Manaus, capital of the sprawling state of Amazonas, was triggered by a new, more contagious variant of the virus, known as P1.

Studies indicate the "Brazil variant," believed to have emerged around Manaus, can re-infect people who have had the original, and may be more virulent.

Public health research institute Fiocruz found P1 in 51 percent of Covid-19 patients in Manaus in December. By January, that had jumped to 91.4 percent.

By early February, the city's average daily death toll from Covid-19 soared to more than 110, nearly triple the first wave.

The lack of hospital beds left victims to suffocate to death at home.

"It was complete desperation," said Adele Benzaken, a doctor and World Health Organization consultant based in Manaus who is closely involved in the fight against Covid-19 in her hometown.

"You have no idea what it is to see families running around to find oxygen canisters, the fights outside places selling oxygen," she told AFP.

"It was like a war -- the chaos of a bombing, when people are running around desperately without knowing what to do."

The first person in the Chaves sisters' family to get Covid-19 was their father, Marcio Moraes, a 43-year-old nurse technician on the front line of the pandemic.

He was briefly treated at a hospital -- and then sent home because there was not enough room.

The sisters borrowed 6,000 reais ($1,035) and bought him a small oxygen cylinder.

Soon, seven other relatives came down with Covid-19, and they had patients in every room of the house.

Despite donations from friends and neighbors, the family estimates they have spent about 20,000 reais out of pocket on medical expenses -- mostly on oxygen.

At the height of the crisis in January, the price of a 50-liter oxygen cylinder leapt from 1,000 reais to as much as 6,500 reais, as desperate buyers turned to the black market.

Police would escort oxygen shipments from overwhelmed suppliers and guard them at the hospital.

Amid the chaos, some sellers were caught painting fire extinguishers green to pass them off as oxygen tanks.

Other residents describe terrifying ordeals in overflowing hospitals.

When Josimauro da Silva, a 57-year-old mechanic with diabetes, developed severe Covid-19 symptoms, his daughter Jessica rushed him to the emergency room.

But after spending the night in the corridor with more than 100 other patients, he told his daughter, "Get me out of here."

People were dying all around him, he told her. There were no beds, oxygen, doctors or nurses to deal with so many sick people at the same time.

Jessica has been caring for him since. It is such an all-consuming job she barely finds time to sleep or eat, she said.

"I'm becoming a zombie," she told AFP.

Her father went through 20 50-liter oxygen cylinders in three weeks of treatment.

Jessica managed to pay for them thanks to donations from friends and family.

"Whoever could afford it bought oxygen, or took a plane out of Manaus if they could," said Fiocruz researcher Christovam Barcellos.

"The city was abandoned to the poor."

Even relatively well-off families have resorted to caring for loved ones at home.

Lying on an impromptu sick bed in his living room and connected to an oxygen tube, 36-year-old IT analyst Thiago Rocha told the story of how his family decided to bring him home after checking him into a hospital, only for his condition to deteriorate.

"I was very scared," said Rocha.

His upper-middle-class family estimates they have spent more than 10,000 reais on his care -- a small fortune to many Brazilians.

Public health experts say Manaus made missteps.

Officials caved to "political pressure" to fully reopen the economy, said Barcellos.

The city voted in the 2018 presidential election for far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, who has flouted expert advice on containing the pandemic, even as Covid-19 has claimed more than 280,000 lives in Brazil -- the second-highest toll worldwide, after the United States.

Years of under-investment and corruption also sapped the public health system.

But the city's story should serve as a warning, said Benzaken.

The P1 variant is spreading fast. It has reached more than two dozen countries, including the United States, Britain and Japan.

Studies indicate several vaccines are effective against it -- a relief. But the question is how far it can spread before people are vaccinated.

And other dangerous variants could emerge.

"This crisis could happen elsewhere," said Benzaken.

"Manaus is like a laboratory for what comes next."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.