The Curious Case Of Rodney Fox, The Shark Attack Survivor Who Became The Great White’s Biggest Advocate

ADELAIDE, Australia -- There’s a moment in everyone’s life when suddenly, with unflinching clarity, you realize that nothing will ever be the same again. For 73-year-old Rodney Fox, that epiphany came with a thud on Dec. 8, 1963, the day he endured one of the worst nonfatal shark attacks in history.

It was Aldinga Beach, 45 minutes south of Adelaide, and spearfishing was all the rage. The then-23-year-old life insurance salesman was on what he called “a bit of a hunter-gatherer streak,” and this day he was out to defend his title at the South Australia Spearfishing Championships. He’d been spearfishing for about four hours and still hadn’t found the fish he needed, so he swam out deeper than the rest of the pack to about 60 feet and, just when he was about to strike, he felt a huge thump on his chest.

“I thought I’d been hit by a train, of all things,” he recalled. But then he saw the teeth.

What Fox said happened next is, quite frankly, unbelievable. It’s the stuff of Hollywood movies -- the kind he would go on to create after his remarkable return from almost-certain death.

“I knew instinctively that the shark’s eyes were the most vulnerable,” he said. “So I gouged its eyes and it seemed to stop and let me go. But as I fell out of its mouth, I pushed the shark away and my hand went straight into its mouth and ripped open. Then I put the shark in a bear hug and, holding on like that, I realized that I was still holding my breath and snorkeling about 50 feet under the water and I was going to drown.”

Fox pushed off toward the surface, but his ordeal was far from over. As he looked back down through the pink water, the great white raced up, bit down on his float line and dragged him back under. Then, he said, a series of miracles happened.

First, the line snapped. Then, a boat came over to investigate the blood-splotched water and raced Fox to the shore where, for the first time ever, there was a car waiting at this largely inaccessible beach. The car's driver raced Fox to Royal Adelaide Hospital, where doctors pieced him back together with 462 stitches. They said at the time that he surely would have died if he’d arrived just a minute or two later.

How many of the details in this remarkable tale are 100 percent factual and how much is a myth solidified over the past five decades is irrelevant, because what happened after that shark attack 50 years ago is arguably even more interesting than anything that took place in the water that day.

“My shark attack occurred in a period when nobody really knew anything much about sharks at all,” Fox recalled. “In the hospital, I realized there was a real fear and hatred. Everybody wanted to go out and kill the sharks, but all I wanted to do was learn more about them.”

It was with that self-actualization, not from the bout in the water, that Fox’s life was forever changed.

A Little Film Called "Jaws"

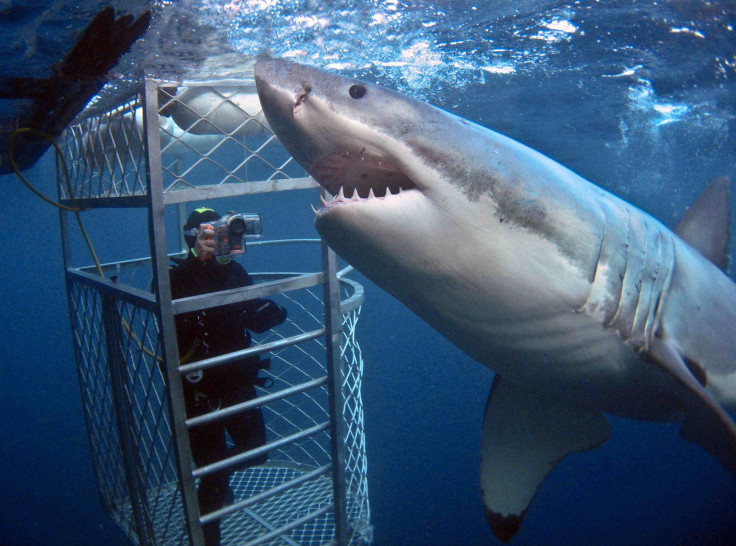

Fox found himself in the lion exhibit at Adelaide Zoo about six months after the attack when an idea struck him like lightning: What if we reversed roles? What if we put humans inside something like a lion cage and placed them underwater? The idea provided him with a way, he said, to get back into the ocean and decide for himself how he really felt about the great whites.

The shark attack survivor went on to pioneer the world’s first shark-cage dive operation -- more as hobby than anything else -- to capture some of the earliest underwater footage of the feared predators. His hobby turned into a profession after clips of the great whites he shot with friend Ron Taylor landed on the desk of a young director by the name of Steven Spielberg who was making a little film called “Jaws.”

Little did Fox know that his underwater footage of great whites off the coast of South Australia would go on to scare the bathing suits off movie audiences the world over. “I didn’t tell people I worked on ‘Jaws’ for a while because I didn’t want to frighten them; I wanted them to come and see the sharks,” he recalled.

But Fox would soon have his chance. While “Jaws” terrified many, it inspired a group of U.S. tourists to book a trip out to South Australia in 1976 for a chance to view the still-mysterious fish face to face in Fox’s underwater cage. Shark ecotourism was born.

Fox went on to gain protection for the great white sharks in Australian waters and initiated the first code of conduct to protect sharks from exploitation. Operators from California to South Africa have since adopted his model as shark-cage diving spread around the world.

According to a study published in June by the University of British Columbia, or UBC, shark ecotourism is today a $314 million industry, and one that’s expected to double to $780 million over the next 20 years. For comparison, the global trade in shark parts is estimated to be worth $630 million and has been in decline for the past decade.

Each year more than 73 million sharks are killed to serve the food industry's demand for fins, predominantly in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Many of the sharks slaughtered in the multimillion-dollar trade industry are immediately thrown back into the ocean to die after their fins are removed for sale at prices of as much as $800 per kilogram ($364 per pound).

Yet Andres Cisneros-Montemayor, a Ph.D. candidate with UBC’s Fisheries Economics Research Unit and lead author of the shark ecotourism study, said his research proved that sharks are much more valuable in the ocean than in a bowl of soup.

“The emerging shark-tourism industry attracts nearly 600,000 shark watchers annually, directly supporting 10,000 jobs,” Cisneros-Montemayor explained. “It is abundantly clear that leaving sharks in the ocean is worth much more than putting them on the menu.”

In Australia and New Zealand alone, 29,000 shark watchers help generate nearly $40 million in tourism expenditures each year, according to the study. This suggests that the continued protection of shark species could have important economic benefits not just to the traditional locations that have dominated the industry such as Australia, South Africa and the Caribbean, but to smaller players as well. Some 99 countries have now banned shark finning, while nine nations and territories -- the Bahamas, the Cook Islands, Honduras, Palau, the Maldives, Tokelau, the Marshall Islands, French Polynesia and New Caledonia -- have created sanctuaries prohibiting commercial shark fishing in recent years to protect the animals in their waters.

This is exactly the kind of conversation Fox had in mind when he sent that first cage into the water nearly five decades ago. And it’s the reason he still goes out on the expedition boat to this day -- to see the looks on people’s faces when they emerge from the cage.

“It makes me realize that what we’re doing is making a difference," he said. "We’re showing people one of the most feared predators and teaching them to understand it better. Hopefully they’ll learn to look out for the sharks and they’ll learn to protect them.”

Sharks, the Sea and Me

The hair-raising tale of the Fox and the shark has been told many times during the past 50 years. The septuagenarian has wined and dined with film stars and princes. He even found himself in a cage with Miss Universe, a claim to fame so audacious that even Fox had to chuckle at the thought.

All the while, he’s spent nearly every moment of his adult life not only facing his fears but forcing others to come to terms with theirs. In the process, Fox has become a world-renowned shark authority and advocate who’s worked on more than 70 documentary and feature films for the likes of IMAX, Disney, Discovery Channel and National Geographic, which collectively form a large percentage of our common knowledge about sharks.

In addition to the cage-diving operation Rodney Fox Shark Expeditions, now run by his son Andrew off South Australia’s Neptune Islands, Fox paired up with his son and Dr. Rachel Robbins in 2002 to form the Fox Shark Research Foundation, which helps instill an appreciation and understanding of great whites through research and education. The Foundation sponsors Ph.D. students, studies the dwindling populations and has already tagged roughly 400 sharks (like Strappy, Chompy and Mrs. Moo) to track migrations.

The conservationist, filmmaker, ecotourism pioneer and shark attack survivor will soon add yet another item to the list of achievements in his illustrious career: author. On Dec. 8, 2013, 50 years to the day after his attack, Fox will release his autobiography, “Sharks, the Sea And Me.” It’s just another milestone in a cathartic journey for a man who never tires of sharing his life story and can’t believe he’s survived this long without any major problems stemming from the physical trauma of the attack.

“When I look back at photos of my attack, I think to myself: I must have been left on earth to do something really important," Fox told IBTimes. "I must have been left here for some special reason. I’ve been waiting to be pointed in the right direction -- to figure out what that reason is, but all I’ve ever seemed to do is talk about sharks.

“All I’ve ever really done is try and get people to understand them just a little bit better.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.