In Davos, The Spectre Of A Tech Cold War

China and the United States may have laid down their arms for now in a trade truce, but their technological rivalry is still raging, raising the spectre of a high tech cold war.

The coming battle played out this week in the corridors of the World Economic Forum in Davos, where Chinese executives rubbed shoulders with Silicon Valley supremos, and US diplomats lobbied hard to keep companies from embracing Made in China for their tech revolution.

At the centre of this cold war 2.0 is Huawei, the Chinese telecom giant whose 5G technology is key to delivering artificial intelligence (AI) and the next generation of computing.

Despite the idyllic winter setting, the tensions over Huawei between Beijing and Washington couldn't be higher.

Huawei has been banned from the United States, which insists on the risk of Chinese espionage and implores its European allies to do the same as the company rolls out deals in major emerging markets led by Brazil and India.

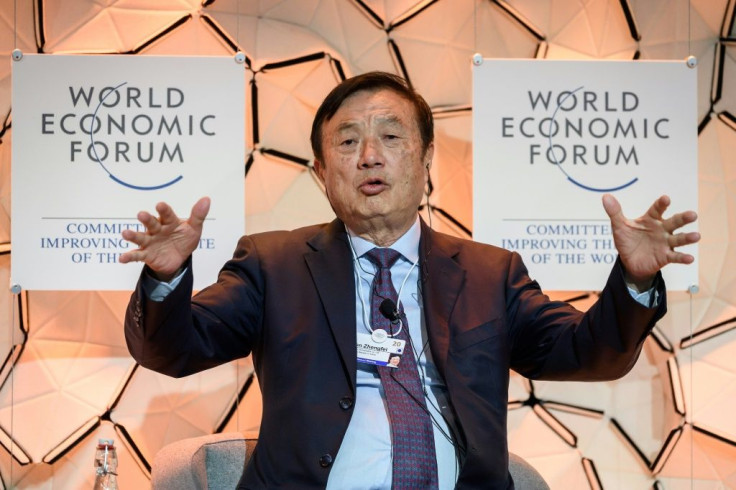

Making matters personal, company founder Ren Zhengfei, a Davos star this year, came to the snowy resort just as his daughter, the company's chief financial officer, was being grilled in Canada for extradition to the US where she is wanted on charges of fraud and breaking US sanctions against Iran.

"A world divided? I don't believe it," Ren told to an audience of CEOs and top executives, avoiding all controversy.

But experts assessing this new battleground warn the world is entering a digital schism.

"There is a competition for the predominance globally on digital questions. Huawei is a symbol of that but it runs much deeper," Carlos Pascual, a former US diplomat and vice-president of IHS Markit, told AFP.

For Pascual, cyber-conflicts and "battles of influence" are paving the way for "a major Sino-American confrontation".

The confrontation ratcheted up in 2015 when Beijing adopted the "Made in China 2025" programme to boost its technologies, along with a massive infrastructure investment plan for the "Silk Roads" to Asia, Europe and Africa.

"This could lead many developing countries to look to China to build their telecom networks, relay stations, data centres and government IT systems," said John Chipman, head of the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

He noted that as they expand across all continents, Chinese companies are also gaining access to troves of data, the key to developing AI and the foundation for tomorrow's economy.

Washington, irked by this data harvesting, has also blacklisted several Chinese cybersurveillance and facial recognition firms.

Meanwhile, Chinese internet giants Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, pushed by Beijing, are developing AI platforms, autonomous cars or connected objects distinct from those developed in Silicon Valley by Google or Amazon.

"The concern is that there will be two types of systems that are not compatible. Technology is an issue of power and a bipolarisation is taking place," said Jacques Moulin, head of the European think tank Idate.

Jean-Philippe Courtois, executive vice-president of Microsoft, echoed fears of a digital divide in global standards.

"The risk is that the tectonic plates" of the major technological markets "will become more and more fragmented or more and more distant", Courtois, who leads global sales for the US-based giant, told AFP.

"Our role is to take charge of this complexity by offering companies tools adapted to each regulatory environment," said Courtois whose company, along with Apple, is still largely dependent on Chinese suppliers.

At the same time, China strictly regulates its domestic internet, reinforcing the concept of a "splinternet" around the world as companies are forced to adopt different approaches depending on the market.

Can China meet its ambitions? In 2018, the telecom equipment manufacturer ZTE, another 5G giant, nearly disappeared, unable to import American components after a ban by the Trump administration that was finally lifted.

The episode was traumatic for Beijing and highlighted the Asian giant's dependence on American semiconductors: in total, China imports more chips than oil in terms of value.

Under the US pressure, Huawei has been developing its own chips and its recent Mate 30 Pro model no longer contains US components, according to a Japanese firm that has taken the device apart.

Qualcomm, the US microchip giant, has suffered blowback from the sanctions against Huawei, but said the situation wasn't lost.

"During the peak of the trade tensions our collaboration with China actually increased," company president Cristiano Amon told AFP, citing partnerships with Xiaomi and Oppo.

For these companies to "grow outside China, you need to work with international global standards and you need to partner with companies like Qualcomm".

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.