Dylan, Young, Fleetwood: Music Publishing Sector Booming With High-profile Sales

The pandemic has left the performance industry reeling but music publishing, a normally under-the-radar side of the business, is roaring thanks to a frenzy of high-profile music catalog sales.

The royalty streams of songwriting copyright portfolios can prove lucrative for the long haul, and increasingly are enticing investors even as other industries tank under the pandemic's weight.

In many cases, the transactions have come at staggering prices: Bob Dylan sold his full publishing catalog for a reported sum of $300 million to Universal Music Publishing Group, while Stevie Nicks of Fleetwood Mac sold a majority stake in her catalog reportedly for $100 million.

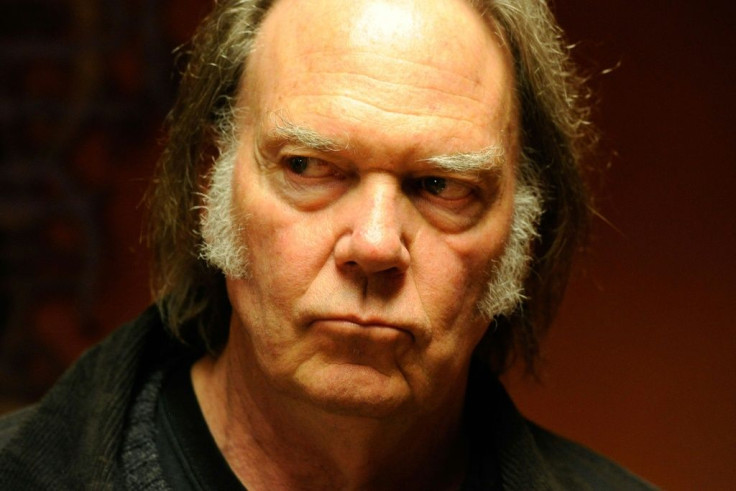

Neil Young and the duo behind Blondie inked deals for undisclosed amounts, as did Shakira. Lindsey Buckingham and Mick Fleetwood, both also of Fleetwood Mac, each recently announced sales that include publishing copyrights to hits including the 1977 song "Dreams," which recently enjoyed a streaming renaissance after going viral on TikTok.

The owners of a song's publishing rights receive a cut in a number of scenarios, including radio play and streaming, album sales, and use in advertising and movies.

The "fantastically positive" sales trend began well before 2020 but rapidly escalated even as other sectors suffered due to Covid-19, said Nari Matsuura, a partner at the firm Massarsky Consulting, which valuates catalogs for lenders and music publishing groups along with private equity and music funds.

Streaming's numbers have soared in recent years and appear sound long-term. That anticipated stability combined with low interest rates and dependable earning projections for time-tested hits have fostered music publishing's bull market, she said.

Meanwhile, many artists unable to tour have looked to monetize their other assets, namely songwriting catalogs, as the valuations of their work continue to rise.

"We have seen names, these incredibly iconic artists... (who) we never imagined would sell," Matsuura said.

For some musicians, it makes sense to cash out while they know prices are good. The possibility that the capital gains tax rate could increase under the Joe Biden administration is likely also triggering deals.

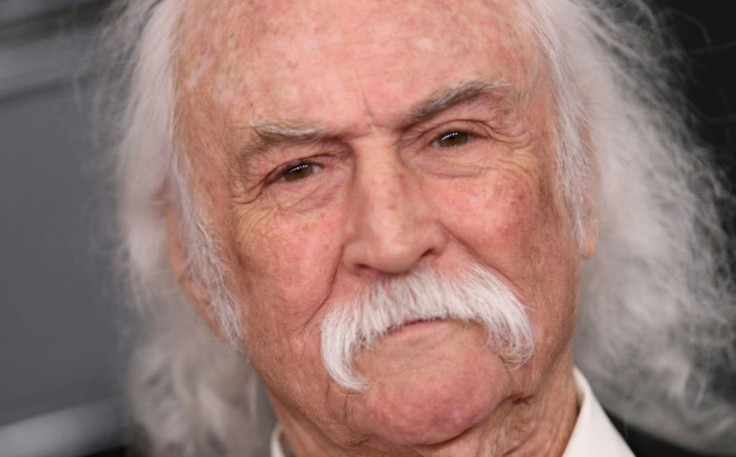

But for David Crosby -- the star singer-songwriter and founding member of both the Byrds and Crosby, Stills and Nash, who said late last year he was selling his own catalog -- it's mostly because the pandemic has halted live performance, which many artists depend on.

"The main reason is simply that we've all been sort of forcibly retired, and can't do anything about it," he told AFP via video chat from his California home.

"I would not have done this deal if I didn't have to."

Crosby also leveled the longtime criticism that streaming services benefit major artists while paying older, cult and up-and-coming musicians extremely little.

The company leading much of the business is Hipgnosis Songs Fund, a British investment and management company introduced on the London Stock Exchange in July 2018.

Other major players include Primary Wave, which struck the Nicks deal, along with funds including Tempo Investments, Round Hill and Reservoir.

Hipgnosis, headed by music magnate Merck Mercuriadis, posits that song revenues operate outside of regular market swings -- that "music is always being consumed and now thanks to streaming almost always being paid for."

"While we would not have wished for a pandemic to demonstrate this, it has indeed done exactly that and that has been reflected in our strong performance," reads its 2020 interim report.

The company has dropped well over $1 billion on catalog acquisitions including from Young, Blondie, Shakira and RZA, and boasts a collection of some 58,000 songs.

For Jane Dyball, former CEO of Britain's Music Publishers Association, it's not that catalog sales are new -- but that there's growing hype around them as an asset class.

"There's always a movement of catalogs, hugely under the radar -- I suppose the thing that's brought everyone's attention to this is just the number of catalogs being acquired by Hipgnosis," she said.

"What's different now is the value is going up because there's a lot of activity," Dyball continued.

"The finance markets obviously feel good about music publishing."

It concerns Crosby, who despite striking a deal for his own catalog, said he longs for the days when fans "paid us for the work we did" and would prefer investment companies weren't scooping up beloved hits.

The terms of artists' contracts and deals vary wildly and are rarely public, but the slew of publishing sales likely mean more songs will be available for licensing in movies, shows and advertisers -- a possibility Crosby laments.

But to those who have dubbed artists as sellouts after they exchange their copyrights for liquidity, the rocker shakes his head.

"They don't know anything and they're jealous," he said. "I can't play live -- and they won't pay me for my recordings."

"What should I do?"

mdo/mdl

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.