Earth Environments Suffer After Years Without Dinosaur Poop

When the dinosaurs went extinct about 65 million years ago, they took their poop with them. And that was a big loss for the Earth.

Scientists say our planet was far more fertile during the age of the dinosaurs, because large animals like the prehistoric herbivores contributed much more material to the ecosystem than smaller ones. The difference shows that sometimes size does matter: The dinosaurs traveled across greater distances to disperse that crucial dung.

“Animals play an important role in the transport of nutrients, but this role has diminished because many of the largest animals have gone extinct or experienced massive population declines,” the researchers wrote in their study, in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “The past was a world of giants, with abundant whales in the sea and large animals roaming the land.”

The team compared how nutrients cycled through Earth’s land, water and air during different periods, by looking at concentrations of different elements deposited through time. Researchers say that nutrients are dispersed about 92 percent less than how much they traveled on land in the time of the biggest land animals, and about 95 percent less in the oceans.

“We propose that in the past, marine mammals, seabirds, anadromous fish, and terrestrial animals likely formed an interlinked system recycling nutrients from the ocean depths to the continental interiors,” the study explains. “With marine mammals moving nutrients from the deep sea to surface waters, seabirds and anadromous fish moving nutrients from the ocean to land, and large animals moving nutrients away from hotspots into the continental interior.”

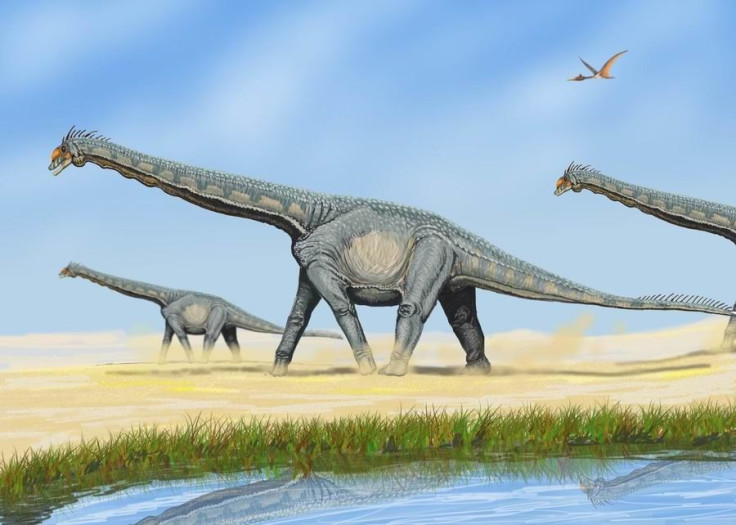

Although we still have large animals like elephants and whales, much of the world’s biggest animals have already come and gone. The biggest of the big were the titanosaurs, a group of herbivorous dinosaurs within the sauropod family, which was known for having long tails and long necks that held up small heads — so they could reach vegetation in the treetops, like today’s giraffes.

Of those titanosaurs, the biggest one discovered is the recently named Patagotitan mayorum, whose bones were found in South America. It was about 122-feet long and weighed between 126,000 and 138,000 pounds while it was alive. It was the biggest land animal to ever live — for comparison, elephants at their largest will be about 20 feet long and weigh about 13,000 pounds — and walked the Earth during the Cretaceous period, which ran between 66 million and 145 million years ago.

Our planet still has, however, one behemoth: the blue whale. Those marine mammals can be 100 feet long and weigh 400,000 pounds. But as the study notes, whale populations have decreased in recent centuries.

An animal’s digestion is part of the cycle through which nutrients are processed, and larger animals simply carry a larger load.

“Nutrients can be locked in slowly decomposing plant matter until they are liberated for use through animal consumption, digestion and defecation,” the study said.

When large animals are absent, those nutrients are released more slowly, only coming out as the plants decompose without animal help — “making the entire ecosystem more nutrient-poor.”

The southern part of South America, where the Patagotitan once lived, has been hit particularly hard because it used to have such a tremendous population of enormous creatures, researchers say.

“By increasing the abundance and distribution of elements like phosphorus, plants grow faster, meaning large herbivores are responsible for producing their own food and contributing to their lush habitats,” according to a statement from Northern Arizona University.

Researcher Christopher Doughty explained that the findings are important for understanding today’s environment.

“We are rapidly losing our remaining large animals, like forest elephants, and this loss will critically impair the future functioning of these ecosystems by reducing their fertility,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.