Ethiopia's Abiy Faces Outcry Over Crackdown On Rebels

Desta Garuma, a 27-year-old rickshaw driver, never showed much interest in politics, so his family has no idea how soldiers concluded he was involved in a rebel movement active in Ethiopia's Oromia region.

But one day in January, five truckloads of soldiers followed him home, shouting that they had identified a shifta, or bandit -- a euphemism for rebel.

As his mother and younger sister cowered inside, the soldiers fatally shot Desta three times in the back, according to witnesses.

"When I heard the shots I said, 'Oh my God, they killed my son,'" Desta's mother, Likitu Merdasa, told AFP.

"My son was not a troublemaker. We hoped he would be able to improve his life as well as mine. But now he has been taken from me before his time."

The killing is one of an array of abuses that residents, opposition politicians and rights groups accuse soldiers of committing in and around Nekemte, a market town in Oromia, as part of a crackdown on rebels that has intensified this year.

Community leaders contend ordinary civilians are bearing the brunt of the operations, which include mass detentions, an internet blackout and restrictions on political activity.

The Ethiopian military rejects claims that its activities endanger civilians.

Yet Nekemte residents say the soldiers' presence recalls life under past authoritarian regimes in Ethiopia, tarnishing the image of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, the Nobel Peace laureate trying to steer the country toward landmark elections in August.

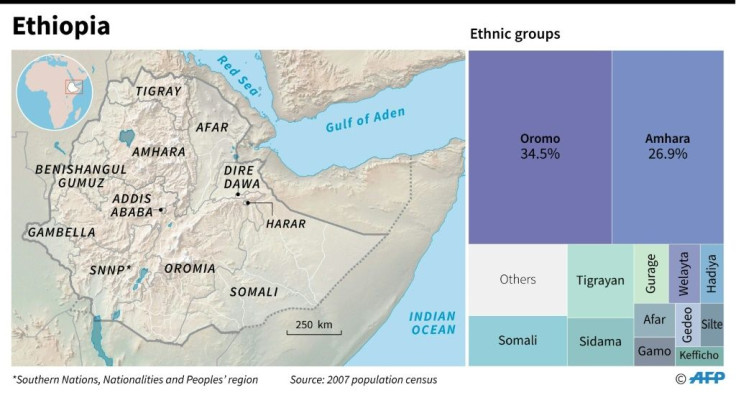

This is especially disheartening for the Oromo ethnic group, who had hoped they would benefit from the appointment of Abiy, himself an Oromo, as prime minister in 2018.

"When the reform came, we all hoped this kind of thing would not happen to Oromo people," Likitu said.

"But now they're coming to the doors of our houses and killing our children in front of us."

The military is ostensibly targeting the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), blamed for a spate of assassinations, bombings, bank robberies and kidnappings in Oromia.

The OLA, believed to number in the low thousands, broke off from the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), an opposition party that spent years in exile but was allowed to return to Ethiopia after Abiy took office.

The government has offered little specific information about military operations in Nekemte and the broader region that surrounds it, known as Wollega.

But there are signs that counterinsurgency efforts have escalated since January, said William Davison, Ethiopia analyst for the International Crisis Group (ICG), a conflict-prevention organisation.

"It appears the government decided to make a renewed effort to entirely remove the threat of armed groups from the area," Davison said.

Brigadier General Tilahun Ashenafi, foreign relations director of the Ethiopian National Defence Forces, defended the military's actions, saying he had "no idea" about civilian casualties.

Soldiers are acting in a "very good way in that region in order to clear anti-peace elements", he told AFP.

But many residents of Nekemte see the military, not the rebels, as the main source of instability.

Asfaw Kebede, a 60-year-old community leader, told AFP he grew alarmed last year at the jailing without charge of young men in Kumsa Moroda Palace, a one-time tourist attraction that residents said had been turned into a makeshift detention facility.

When Asfaw started bringing the men food, soldiers locked him up too, holding him in a dark cell for six weeks with roughly 100 other detainees.

All the men were deprived of proper food and medical care, Asfaw said.

The palace teemed with snakes and mice, and when they entered the cells inmates who scrambled to get away were beaten with batons, he said.

Opposition political parties have also been affected by the military presence.

Representatives of both the OLF and the Oromo Federalist Congress said their offices had been closed multiple times and their members detained.

Such tactics are fuelling sympathy for the OLA, said Tamirat Biranu, head of an evangelical church in Nekemte.

"Young people are very sad about this and also they are angry at the government," he said. "Because of this, some of the youth are joining the rebels."

As bad as things might be in Nekemte, they are likely worse in rural areas farther west, where phone service has been cut for months, said Asebe Regassa, a lecturer at Wollega University.

"Killings are occurring on a daily basis in rural areas," Asebe said, adding that farmers are afraid of harvesting their crops, fearing soldiers will accuse them of growing food for the OLA.

The military operations are "clearly taking a heavy toll," said Laetitia Bader of Human Rights Watch (HRW).

"Ahead of the 2020 national elections the government should be working to build trust with communities," she said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.