Evolutionary Facebook Discovered, Primates Have Been ‘Relying On The Face’ For 50 Million Years [PHOTO]

Facebook may have been founded in 2004, but monkeys have been posting their version of status updates for millions of years, a new study suggests.

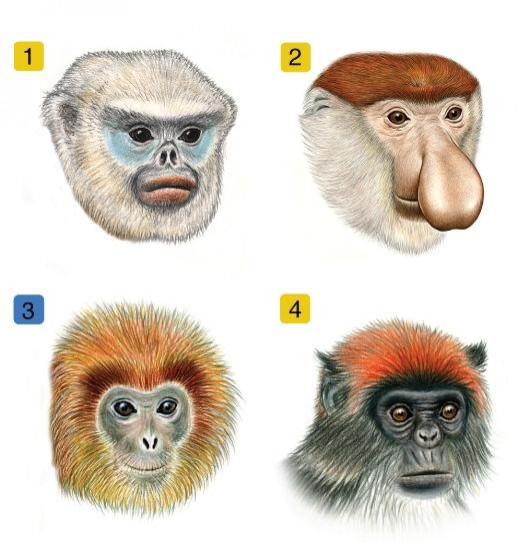

Biologists from the University of California Los Angeles studied the evolution of 139 primate faces that have changed over some 25 million years. The findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, explain how scientists identified complex facial patterns that they believe primates have used in face recognition.

"Humans are crazy for Facebook, but our research suggests that primates have been relying on the face to tell friends from competitors for the last 50 million years and that social pressures have guided the evolution of the enormous diversity of faces we see across the group today," Michael Alfaro, an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology in the UCLA College of Letters and Science and senior author of the study, said in a statement.

The 139 Old World African and Asian primate species involved in the study are social creatures by habit. Unlike solitary species like orangutans, Old World species can live in groups of up to 800 members.

"Our research suggests increasing group size puts more pressure on the evolution of coloration across different sub-regions of the face," Alfaro said. Larger groups let member species develop "more communication avenues” and “a greater repertoire of facial vocabulary.”

Scientists used photos of primate faces. She divided each face into several regions, and classified each face’s color, hair and skin. Each face was assigned a score based on the total number of different colors on its facial regions. The biologists then determined how the complexity scores were related to social variables including environmental factors like geographic location, canopy density, rainfall and temperature.

"Our map shows clearly the geographic trend in Africa of primate faces getting darker nearer to the equator and lighter as we move farther away from the equator," co-author Jessica Lynch Alfaro said.

The team also discovered that primates’ facial complexity is determined by the size of its social group.

"We found that for African primates, faces tend to be light or dark depending on how open or closed the habitat is and on how much light the habitat receives," Alfaro said. "We also found that no matter where you live, if your species has a large social group, then your face tends to be more complex.”

These results are the polar opposite of the ones the same biologists had with a similar study they published last year using primates from Central and South America. For those primates, the one that lived in larger groups had plainer faces.

Within the Old World group, biologists found that different primate groups used their faces differently. For instance, great apes had plainer faces than monkeys. One reason behind this could be attributed to facial expressions.

“These expressions would be obscured by more complex facial color patterns,” Lynch Alfaro said. “There may be competing pressures for and against facial pattern complexity in large groups, and different lineages may solve this problem in different ways."

The findings may be able to help describe the evolution of human faces.

"Humans don't have all these elaborate facial ornamentations, but we do have the ability to communicate visually with facial expressions," Alfaro said. "Does reduced coloration complexity create a blank palate for visual expressions that can be conveyed more easily? That is an idea we are testing."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.