Fast Radio Bursts: Mysterious Signals Flash Every Second

Every single second there is a fast radio burst happening somewhere in our observable universe, even if we do not detect it here on Earth. That’s according to the estimates of a research team that analyzed the mysterious radio signals from space, which we only just discovered in 2001.

Fast radio bursts, or FRBs for short, are bright emissions of light at the radio wavelengths of the spectrum that last for just milliseconds. After first catching one for the first time several years ago, scientists have seen almost two dozen total. To determine how often they occur, the scientists based their calculations, for a study in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, on how fast radio bursts have been detected and their apparent source in the night sky.

Most of the detected fast radio bursts were one-offs, but one of them has been found to repeat, giving scientists a chance to pinpoint its source: a galaxy 3 billion light years away from us that is low on metal.

The scientists toyed with the idea that this repeating phenomenon, called FRB 121102, was typical for fast radio bursts and applied its properties to the rest of the section of the universe that we can observe from Earth in order to estimate how many are happening at any one time.

“It exceeds one FRB per second per sky when accounting for faint sources,” the study says.

That still doesn’t solve the mystery of what causes fast radio bursts, but it adds to our understanding of them.

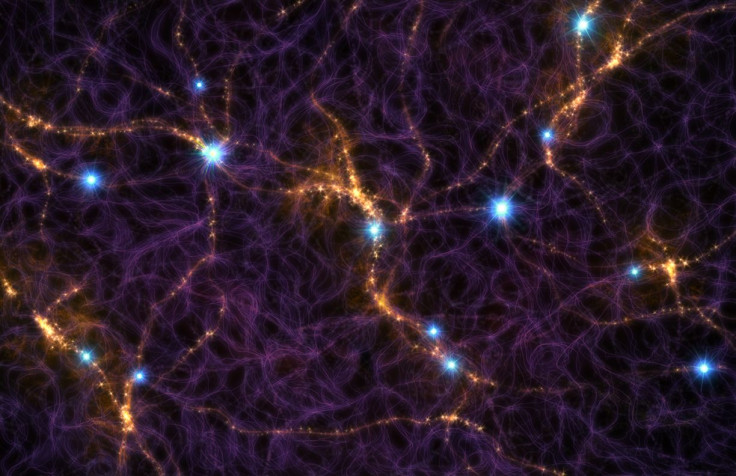

“If we are right about such a high rate of FRBs happening at any given time, you can imagine the sky is filled with flashes like paparazzi taking photos of a celebrity,” researcher Anastasia Fialkov said in a statement from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. “Instead of the light we can see with our eyes, these flashes come in radio waves.”

Part of the problem in studying fast radio bursts is how few of them have been observed, a function of how difficult they are to catch; they are gone as quickly as they appear. It’s possible, however, that more advanced radio telescope technology will be able to lock onto more of them.

“In the time it takes you to drink a cup of coffee, hundreds of FRBs may have gone off somewhere in the universe,” researcher Avi Loeb said. “If we can study even a fraction of those well enough, we should be able to unravel their origin.”

Some scientists believe they all come from young neutron stars, which are the dense leftovers after a huge star explodes in a supernova.

Regardless of their origins, they can tell us more about how the early universe and how it evolved. As the Center for Astrophysics points out, fast radio bursts can shed light on events happening long distances from Earth, giving us a boost in being able to observe and understand them.

“FRBs are like incredibly powerful flashlights,” Fialkov said. “This could allow us to study the ‘dawn’ of the universe in a new way.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.