Fear Of Execution, Faulting The Government: Haiti Kidnap Victims Tell Of Ordeal

Living in squalid conditions, fearing execution and constantly being shuffled to new locations -- a nun who was among a group of 10 people captured in Haiti told AFP she believed their bodies would be burned or dumped into a mass grave.

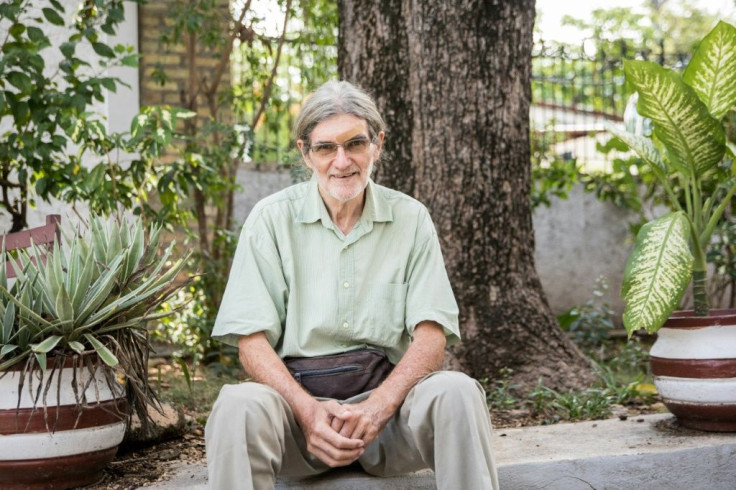

But Michel Briand, a 67-year-old priest also in the abducted group, said he does not blame his captors for the ordeal. He faults Haiti's public authorities.

Undermined by extreme poverty and political instability, Haiti has seen a recent increase in violent gangs in its poorer neighborhoods, which the country's meager public investment efforts have passed over.

The abduction of the 10 in Croix-des-Bouquets, a town northeast of the capital Port-au-Prince on April 11, has become the most visible example of the country's recent spike in kidnappings for ransom.

Briand, and nun Agnes Bordeau, 80, told AFP they were en route to a priest's ordination when their group came upon a dozen armed men who had blocked the road on the outskirts of the capital.

"We were in the wrong place at the wrong time," said Briand, who believes the gang members had not planned their kidnapping.

"As I entered the forest I saw a fire," Bordeau told AFP. "And I thought, 'Oh that's it, they're going to kill us and then they're going to burn us.'"

"Very quickly too, I heard the sound of pickaxe strikes against the ground. I said to myself, 'Well, they are in the process of making a mass grave and they are going to throw us in there and kill us,'" she said, now able to laugh at how very dark her assumptions were.

While Bordeau has worked in Haiti since 2019 after spending decades in Central Africa, Briand has been a missionary in the Caribbean since 1986 and speaks fluent Creole, meaning he was able to interact with the gang.

He said in the first minutes, the men "did not know where to put us," and later threw cardboard on the ground, which became the captives' home for five days.

The captives were moved constantly, with each change eliciting hope of release and fear of execution, Bordeau said. Throughout the entire ordeal, no one in the group, which included French and Haitian clergy plus lay people, was ever attacked.

"The third place was the most terrible because it was unsanitary, really small, and they decreased our food," Bordeau said calmly.

"We would have a meat pie around 3:00 pm, a bottle of water and that was it for the day."

Still not knowing the details of their release, Bordeau and Briand were freed overnight on April 30 along with four others. Another four were freed previously. The group had been held for a $1 million ransom.

"I do not hold it against them and I would even say that they are not responsible," Bordeau said.

"I pray for them a lot, for them to be able to leave this hell where they live," she said, clasping her hands on her knees.

"They fall back on theft, or as was the case with us, kidnapping, to support each other and buy weapons, they told us that clearly," Briand said.

Kidnappings have affected both the country's wealthy minority as well as its masses living in poverty.

"Let us ask that the public authorities take action over talking: There is no point to more words, what is needed is action for the good of the people," Briand said.

In Haiti, where links between gangs and public officials are common knowledge, Briand's captors told him they had been funded by elected officials who later lost power, leaving them to turn to thievery for money.

"These elected officials incited the phenomenon of the gangs," he said, careful to avoid naming specific politicians.

On Saturday, for the first time since his release, Briand drove his pickup truck through the streets of Port-au-Prince.

Gray hair tied in a ponytail, voice calm, he said he has no plans to leave Haiti.

"It's not as if, because you have been bullied by a few Haitian people, that all of the people are bullying you," he said.

Were he to depart now, he added, he would consider it a "betrayal."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.