In Financially Distressed Chicago, Public And Private Lines Are Blurred

May 15, 2015, was an important day in the world of Chicago’s city finances. On that day the city reached a deal with Barclays to take over a $100 million soured bet on an interest rate swap. Inked mostly in the early 2000s, these specialty financial products backfired after the 2008 financial crisis, saddling Chicago taxpayers with hundreds of millions of dollars in fees.

But the Barclays swap deal wasn’t the only piece of financial news for Chicago that day. The city also announced that a new chief financial officer, Carole Brown, would soon take charge of the city’s budgets.

At the time, Brown was still with her previous employer: Barclays Capital.

Now, multiple city representatives have told International Business Times that Brown not only had knowledge of the agreement that transferred the lucrative interest rate swap from Swiss bank UBS to Barclays, but that Brown had personally lobbied her superiors on behalf of the deal while she was a managing director at Barclays.

Alderman Scott Waguespack of Chicago’s 32nd Ward told IBT that in a private meeting, Brown described how she had pushed her superiors to accept the deal when she was still at Barclays. “If she was representing them, but then a day later she was sitting with the city, what kind of deal did we get?” Waguespack said. (It wasn't until May 27 that Brown began as chief financial officer.)

The questions illuminate the tricky politics of municipal debt as Chicago wrangles with financial headaches exacerbated by the weight of risky interest rate swaps deals with major Wall Street banks. Mayor Rahm Emanuel has begun paying the lofty termination fees needed to exit the swaps. Others, meanwhile, have pushed Emanuel to follow the lead of cities like Houston and San Francisco and challenge the banks in court to recoup fees they deem unfair.

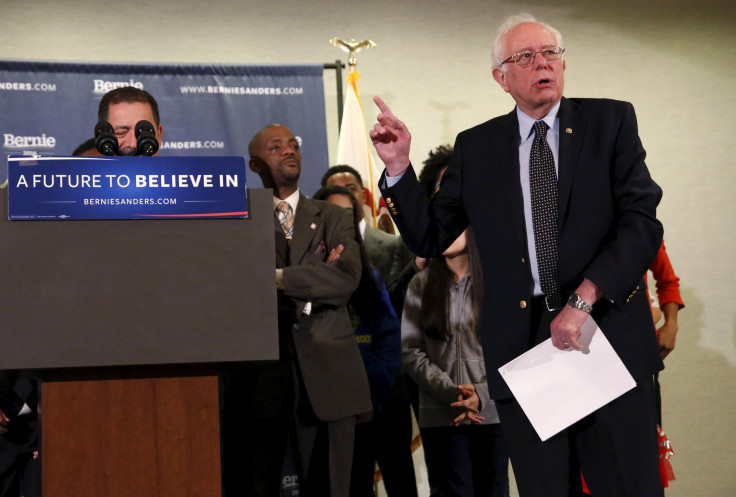

The debate has even made it to the national stage, with Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, a U.S. senator from Vermont, chiding the mayor for leaving the soured swap deals unchallenged. “This city just gave the banks what they asked for and now they want to make the teachers and schoolchildren of Chicago pay the price,” Sanders said Saturday in advance of Tuesday's Illinois Democratic presidential primary election.

The Emanuel administration has already paid roughly $250 million to terminate swap deals with banks including Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo. Most notably, the city rid itself of swaps connected to general obligation bonds, which had been threatened by a sudden ratings downgrade. The swaps, Emanuel explained last year, “exposed taxpayers to greater risk.”

That wasn’t supposed to be the case. When Chicago began entering into interest rate swaps in the early 2000s, they were seen as a useful risk management tool. The product allows a bond issuer — in this case, Chicago — to convert a bond’s payments from a floating rate to a fixed rate, with the bank covering the difference.

“Sometimes the particulars of what they did weren’t so great, but doing a swap is a standard thing,” said Kathleen Hagerty, chairwoman of the Finance Department at Northwestern University's Kellogg School of Management.

In a rising interest rate world, the arrangement could save cities money while smoothing the impact of rate fluctuations on municipal coffers. For the swaps covering the water bonds issued in 2000, for instance, the city pays a fixed 3.87 percent annually, while Barclays pays bondholders the original floating rate. If benchmark interest rates were to rise far enough above that, the city would save money.

But that hasn’t been the case. After the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve pushed interest rates down to virtually zero, where they stood until a slight uptick last December that still left benchmark rates historically low.

Now Chicago, like other municipalities that entered swap agreements in the 2000s, has been left to pay out hundreds of millions of dollars in swap fees, well in excess of what the city would pay to bondholders in the absence of the deals.

Chicago is currently yoked to more than $1 billion in bonds tied to interest rate swaps, which, as of last September, would cost some $216 million to terminate. Chicago Public Schools also hold about $1 billion in bonds covered by swaps. Combined payments on those deals have amounted to more than $100 million a year since the financial crisis, according to estimates from Saqib Bhatti, a research fellow at the progressive Roosevelt Institute.

The agreement reached in May transferred Chicago’s water bond swap from UBS to Barclays, which paid $26 million for the derivative. According to city spokeswoman Molly Poppe, the move was precipitated by UBS's desire to exit the field. "UBS was getting out of the municipal swap business, thus the city was required to find another institution to hold the swap," Poppe told IBT. In lieu of paying the termination fee, Chicago approached Barclays for a transfer.

The deal left the contracts largely intact in all but two respects. First, the city secured a lower bond rating threshold. Swap deals generally specify a lower bound for the credit rating of underlying bonds, below which the swap is terminated and the issuer must repay the swap in full at a cost derived from what the swap would be worth at current interest rates. The lower threshold gives cash-strapped Chicago more breathing room.

But that wasn’t the end of the deal. Buried in the agreement between the city and the two banks was language that clears UBS of any legal responsibilities relating to the swap deal, which took effect in 2008.

According to the deal, UBS “makes no representation or warranty and does not assume any responsibility with respect to the legality, validity, effectiveness, adequacy or enforceability” of the new agreement. In effect, UBS received the full cost of the swap while reducing its exposure to the type of legal challenges that have been raised in Philadelphia and other cities.

That fact didn’t sit right with members of the city’s progressive caucus, who have questioned the Emanuel administration’s finance policy. “Our agreement to not hold given banks liable was not only misguided, it opened an exit strategy for every party in the room except the city of Chicago,” Anne Emerson, a policy consultant to Alderman Waguespack who was present in the meetings with CFO, said.

Previous lawsuits alleging unfair dealing by banks in swaps deals have hinged in part on the widely documented manipulation of an interest rate benchmark called Libor, which undergirds many swaps arrangements. More than a dozen banks have faced investigations over rigging the systemically important benchmark, and UBS has been among the lenders paying billions of dollars in fines after pleading guilty in the scandal.

But a third-party analysis commissioned by Chicago found that the city wouldn’t have much ground to stand on if it wanted to sue. According to the two former federal prosecutors who authored the report, its conclusions “would make it challenging, if not impossible, to claim that the city's counterparties did not deal fairly with the city or that the city did not understand the risks associated with swap transactions.”

UBS employees have contributed more than $71,000 to Emanuel’s campaign efforts since 2010.

Brown’s involvement in internal Barclays discussions of the deal have also set off red flags among representatives. In a legal document sealing Barclays’ takeover of the swap, the bank disclosed that Brown had been approached for the CFO role at the city while the deal was in progress. At that point, “her involvement ceased,” Poppe, the city spokeswoman, said, echoing the Barclays statement. “We do not believe there is a conflict of interest.”

But the arrangement still raised concerns among city aldermen. “I don’t think [Brown] would try to get a bad deal for the city,” Waguespack said. “We just felt like there was something untoward.”

Poppe told IBT that the city paid no fees for moving the swap from UBS to Barclays. But in general, evaluating the city's complex swap-related deals often poses challenges. “There’s a real lack of transparency there, which is a big problem,” Hagerty, the Northwestern professor, said. “It’s really hard to tell how good a job they did.”

As the city moves forward in addressing its debt woes, however, swaps are just one part of a much larger picture, Hagerty said. “They owe a boatload of money. They can’t financial-engineer their way out of this.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.