Finding Life On Mars Through Smell? New NASA Instrument Could Do That

The sense of smell has come a long way in science. First plants that can smell explosives and now machines that can smell Martian life.

Yes, you read that right. NASA is working on an instrument, which when fitted onboard a rover, will allow it to “sniff” for life on Mars and even on other planets. Called Bio-Indicator Lidar Instrument (BILI), the sensor is based on technology currently used by the U.S. military to remotely check the air in public places for potentially lethal chemicals and toxins.

BILI is being developed by Branimir Blagojevic, a NASA technologist at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who previously worked at the company that created the sensor for the military. Using the same methodology, he created a prototype of the instrument for NASA which, in testing, showed it could be used to detect biosignatures on Mars.

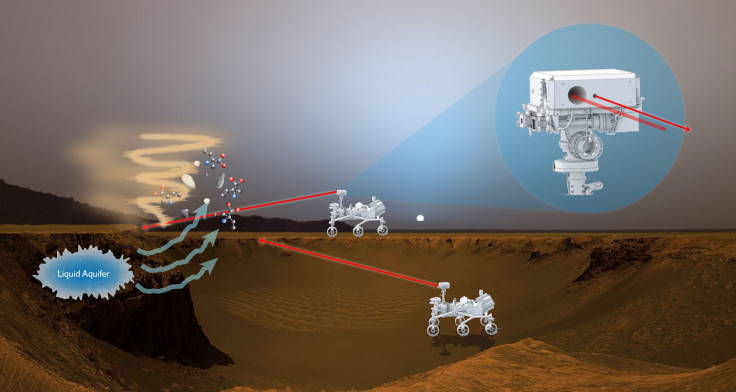

According to a statement on NASA’s website: “BILI is a fluorescence-based lidar, a type of remote-sensing instrument similar to radar in principle and operation. Instead of using radio waves, however, lidar instruments use light to detect and ultimately analyze the composition of particles in the atmosphere.”

The instrument will be positioned on a rover’s mast from where it will scan the terrain for dust plumes. It would then pulse light at the dust from one of its two ultraviolet lasers, causing the particles in the plume to either resonate or fluoresce. “By analyzing the fluorescence, scientists could determine if the dust contained organic particles created relatively recently or in the past. The data also would reveal the particles’ size.”

Given the way it works, BILI can find small amounts of organic compounds from several hundred meters away, a fact that provides multiple benefits. One, it can analyze dust plumes in areas and terrains not easy for the rover to traverse. Two, the distance will reduce the risk of sample contamination that could affect results of the analyses.

“This makes our instrument an excellent complementary organic-detection instrument, which we could use in tandem with more sensitive, point sensor-type mass spectrometers that can only measure a small amount of material at once. BILI’s measurements do not require consumables other than electrical power and can be conducted quickly over a broad area. This is a survey instrument, with a nose for certain molecules,” Blagojevic said.

The instrument can also be installed on an orbiting spacecraft, which could significantly increase the chances of finding biosignatures in the solar system beyond just our neighboring planet, he added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.