Finland In NATO: Strategic Shift With Limited Material Gain

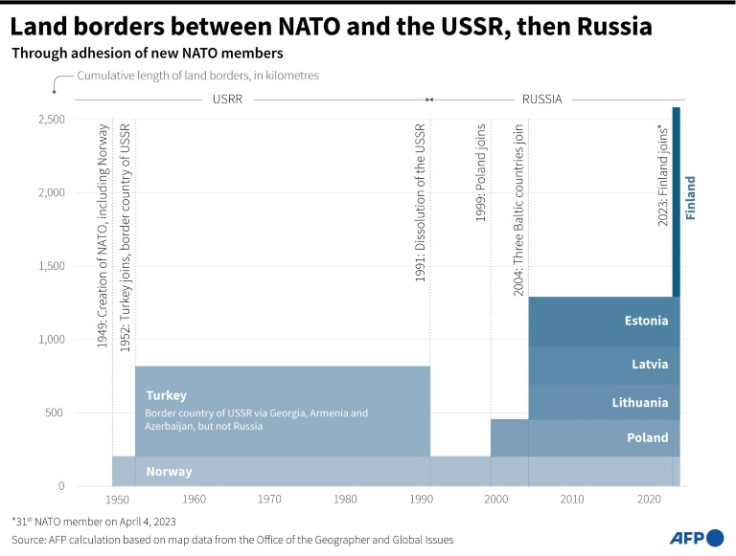

Finland's move on Tuesday to become the 31st member of NATO is a strategic step that doubles the military alliance's border with Russia but provides the coalition with limited additional military capacity.

Here are the key facts:

Finland broke with decades of non-alignment to ask to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization after Russia invaded its pro-Western neighbour Ukraine in February last year.

For Moscow, which has repeatedly warned NATO against expanding, Finland's accession extends the bloc's presence right on its western doorstep.

Russia -- which shares a 1,300-kilometre (800-mile) border with Finland -- said on Monday it would boost its military presence in its west and northwest in response.

With Finland joining NATO, "Russia's northwestern flank becomes more vulnerable", security experts Nicholas Lokker and Heli Hautala wrote on Friday on defence-focused website War on the Rocks.

"Its border with the alliance will then extend from the Arctic Ocean to the Baltic Sea."

As a NATO member, Finland is bound by the alliance's mutual defence clause, Article 5.

It will benefit not only from its allies' conventional military assistance but also from its nuclear deterrence.

In return, the Nordic nation, which intends to boost its defence budget by 40 percent by 2026, could contribute some of its military resources to defend the alliance.

The country of 5.5 million people counts just 12,000 professional soldiers.

But it trains more that 20,000 each year through its conscription service programme, giving the army a pool of 900,000 Finns as potential reserves.

This means that in case of war, the army can deploy 280,000 Finnish citizens at any one time.

It has a fleet of 55 F-18 US combat aircraft, which it plans to replace with more advanced F-35s from 2025 onwards, as well as 200 tanks and more than 700 artillery guns.

But the country joining NATO also means hundreds of extra kilometres of border to defend for the alliance.

The only military equipment that NATO actually owns are a fleet of Airborne Warning and Control System planes (AWACS) -- which can stay in the air for eight and a half hours without refuelling and monitor an area almost as big as Poland -- and five Global Hawk high-altitude surveillance drones.

For all other military gear, each NATO member chooses what to contribute, though all have promised to reinforce the alliance's eastern flank.

For example, France dispatched 500 troops to join US soldiers in Romania last year right after Russia invaded Ukraine. Dutch and Belgian soldiers soon joined them.

As of December, some 5,000 foreign troops were stationed in Romania -- the largest contingent of allied forces on the bloc's southeastern flank.

According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), NATO conducted nine joint exercises last year, from the eastern Mediterranean to the Baltic Sea.

According to the Supreme Headquarters of Allied Powers in Europe (SHAPE), NATO can count on up to 3.5 million soldiers and personnel.

The three nations providing most military staff are the United States with 1.47 million active troops plus 800,000 reservists, Turkey with 425,000 soldiers and 200,000 reservists, and France with 210,000 troops and 40,000 reservists.

NATO has since 2004 had a multinational response force of some 40,000 soldiers on top of the 100,000 US troops already on European soil. It says it hopes to increase this to 300,000 soldiers.

It has also set up a "spearhead force" within it, dubbed the "Very High Readiness Joint Task Force" or VJTF, able to deploy 5,000 personnel in two to three days.

NATO had in recent years faced an existential crisis.

French President Emmanuel Macron in 2019 famously said that NATO was experiencing "brain death" after it failed to respond to Turkey's unilateral invasion of northeast Syria.

But Russian President Vladimir Putin's "re-invasion of Ukraine has provided the fuel for the alliance's renewed unity and recommitment to cooperative security, crisis management, and collective defence," retired general Philip M. Breedlove, who used to head US European Command, wrote in February.

According to IISS, the alliance has since doubled its deployment from four battlegroups -- in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland -- to eight, including Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia.

But "it is likely that most of the high-readiness forces will need to be European", it said in an annual assessment for 2023.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.