First National Blues Museum Planned for St. Louis Riverfront

(REUTERS) - A few blocks from the Mississippi River levee where a homeless W.C. Handy composed St. Louis Blues more than 100 years ago, the first national blues museum in the United States is taking shape.

While several regional blues museums have popped up around the country -- Memphis, Tennessee; Clarksdale, Mississippi; and Helena, Arkansas -- the St. Louis institution will be the first to tell the national story of the unique American musical form.

Organizers say it's time that St. Louis -- a city with a long musical tradition but without the high profile of Chicago, New Orleans or Memphis -- stepped up its visibility in the music world.

The National Blues Museum, which Museum chairman Rob Endicott said he hoped would open next year depending on the final design, would be a part of an ongoing public and private effort to revitalize the St. Louis riverfront.

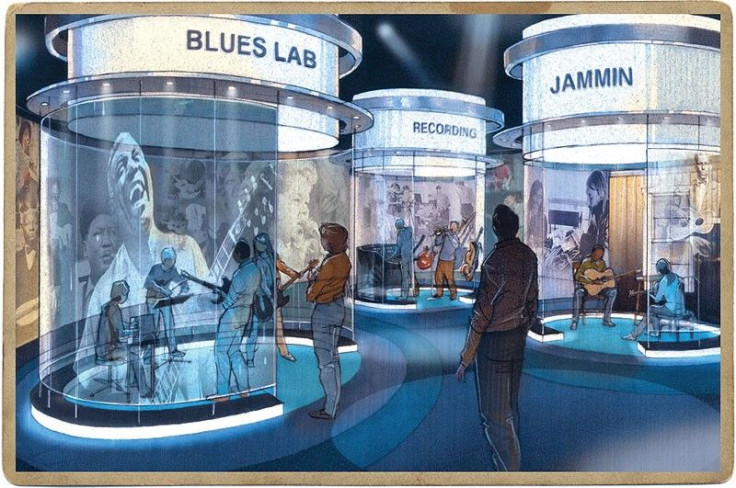

It's going to be kind of space-agey. The idea is to make it a technology-driven, interactive experience. We will have the memorabilia, too, but it won't be a museum of just artefacts, he said.

The museum group, which is using private donations, obtained space in an 1892 department store building that is part of the 1.5 million-square-foot, $250 million Mercantile Exchange District whose development is funded by private businesses that receive state and federal tax credits.

An 11-day Bluesweek celebration that will help support the museum was announced last week. It includes a three-day Memorial Day weekend concert at the downtown Soldiers' Memorial and a blues pub crawl in Soulard, the neighbourhood where the blues in St. Louis were revived in the 1980s.

Headliners for Bluesweek include national blues acts Shemekia Copeland, Bobby Rush, Kelly Hunt and Arthur Williams plus regional acts from St. Louis, Kansas and Mississippi.

RIVERFRONT REVITALIZATION

Groundbreaking on the St. Louis riverfront is set for this year for a $500 million Gateway Arch park rehabilitation aimed at getting more people to walk around the city's downtown, long a maze of highways and empty blocks that discouraged pedestrians.

Tourists come to the Arch and they park and they look at the Arch and they drive away, Endicott said. We want to give them something to walk to.

In the past 10 years, thanks in part to a $100 million state tax credit, the area near the river has grown through loft sales, resulting in a new district of restaurants and bars along Washington Avenue.

The Mercantile Exchange complex being developed on Washington is about three-quarters finished. It includes a hotel, office buildings, the first downtown movie theatre since 2003, and residential and retail space within walking distance of the Cardinals and Rams stadiums as well as the Convention Center and several monumental buildings on Market Street.

The National Blues Museum is one of the retail anchors, developer Amos Harris said. We need to put down a stake for St. Louis music -- to leverage its remarkable history into tourist flow and into the businesses downtown, like Memphis and Chicago have done.

St. Louis has at least as deep a history as these other places -- perhaps deeper -- and we need to inculcate that history into both the people who live here and those from elsewhere, he added.

Another boost to the area is a plan by St. Louis University Law School to move to a nearby building downtown, bringing 1,100 faculty, students and staff.

St. Louis music burst onto the national scene at the time of the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, with the popularity of St. Louis resident Scott Joplin's ragtime compositions. Handy's St. Louis Blues, published in 1914 years after it was written, is one of the most recorded blues songs.

Endicott, an attorney who plays trumpet for the Voodoo Blues band in his spare time, said St. Louis needed to come out of the shadows for U.S. music tourists.

We want to attract the people making the blues pilgrimage, up through the Delta, Memphis, then St. Louis and Chicago, he said.

Blues artists such as Lonnie Johnson, Peetie Wheatstraw and Big Joe Williams were headliners in St. Louis in the 1920s and 30s.

Miles Davis got music training in the city in the 1940s and in the 50s, and Chuck Berry worked on the same stages where Ike & Tina Turner launched their careers. Another wave of St. Louis blues players included Oliver Sain, Henry Townsend, Albert King, Johnnie Johnson and Bennie Smith.

(Reporting By Bruce Olson; Editing by Mary Wisniewski and Cynthia Johnston)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.