Five Questions About Ethiopia's Controversial Nile Dam

Ethiopia said this week it had hit its first-year target for filling the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a concrete colossus 145 metres (475 feet) high that has fuelled tensions with downstream nations for nearly a decade.

Here is a Q&A about the dispute:

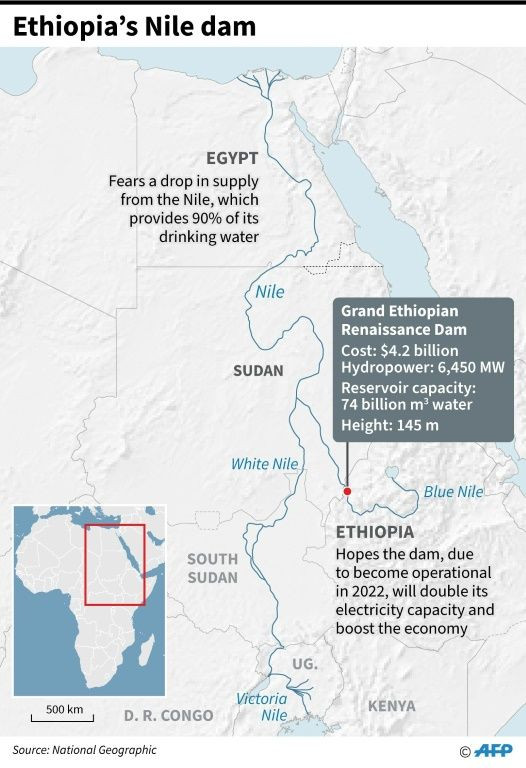

The more than $4-billion (3.4-million-euro) project is situated in western Ethiopia on the Blue Nile, which converges with the White Nile in the Sudanese capital Khartoum before flowing north through Egypt toward the Mediterranean Sea.

Ethiopia's downstream neighbours worry the dam will restrict vital water supplies.

They are especially concerned about what might happen should there be a drought while Ethiopia is still filling the reservoir, a process that will take several years.

Egypt depends on the Nile for about 97 percent of its irrigation and drinking water, and says it has "historic rights" to the river guaranteed by treaties from 1929 and 1959.

Ethiopia was not party to those treaties and does not see them as valid.

It signed a separate agreement in 2010 with other countries, which Egypt and Sudan boycotted, which allows irrigation projects and hydroelectric dams.

Over half of Ethiopia's population of 110 million people lives without power.

The row over the dam intensified in recent months as Ethiopia prepared to begin filling the reservoir, which can hold 74 billion cubic metres (2,600 billion cubic feet) of water.

Egypt and Sudan pushed for Ethiopia to hold off on this until the three countries agreed how the dam would be managed and operated.

But Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has maintained that filling the reservoir is an essential step in the dam's construction.

Last week, Ethiopia acknowledged water was accumulating behind the dam although officials said this was a "natural" part of the construction process.

Ethiopia is in the middle of its rainy season, and officials say the flow of the Blue Nile exceeds the capacity of the dam's bypass channels to send water downstream.

Abiy's office then announced this week that Ethiopia had achieved its first filling target of 4.9 billion cubic metres, which would allow for testing of the dam's first two turbines -- an important step towards generating energy.

Ethiopia hopes to begin generating electricity from the dam by the end of this year or early 2021. The dam has an expected capacity of more than 5,000 megawatts, according to experts.

It is unclear whether Ethiopia took active steps like closing gates to expedite filling of the reservoir, though water was bound to accumulate naturally.

"Ethiopia didn't have to do anything active for the reservoir to start retaining water. The water accumulated as a result of naturally large inflows this year, the hydraulic capacity of the bypass channels, and the current elevation of the structure," said Kevin Wheeler, an engineer at the University of Oxford who has studied the dam.

As construction progresses and the structure grows taller, the dam's spillway is positioned at a higher elevation, meaning more water is retained.

Ethiopia plans to fill the reservoir over five years, though it has expressed a willingness to extend that to seven.

Observers have warned that the dispute over initiating reservoir filling risks distracting from other major areas of disagreement.

These include which mechanism should be used to resolve disputes over the dam's operations and how the dam should be managed during a drought.

Successive rounds of talks have failed to yield a breakthrough on these points.

The African Union is overseeing the current negotiations.

On Tuesday, leaders held their latest virtual summit as part of that process, with all parties saying afterwards there was an agreement to continue talks.

But it is unclear what progress has been made.

With Ethiopia celebrating hitting its first-year filling target, Egypt could come under pressure at home to take a harder line going forward.

Mostafa Kamel el-Sayed, a professor of political science at Cairo University, described recent events as "a debacle for the Egyptian diplomacy".

"Since there is no indication that the Ethiopian government has relaxed its position, we are completely in the dark," he said.

"It is very surprising that the Egyptian government accepted the resuming of the negotiations."

The dam has long been a source of national pride in Ethiopia.

The country broke ground on it in 2011 under then-Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, who pitched it as a catalyst for poverty eradication.

Civil servants contributed one month's salary towards the project that year, and the government has since issued dam bonds targeting Ethiopians at home and abroad.

Nearly a decade later, the dam remains a potent symbol of Ethiopia's development aspirations.

It also offers a rare point of unity in an ethnically-diverse country undergoing a fraught democratic transition and awaiting elections delayed by the coronavirus pandemic.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.