Fossils Of Ancient Flat Sea Animals Tell Us About Evolution, Human Ancestry In Ocean

If you want to imagine what Earth’s first animals looked like, picture a bunch of bathmats swimming around in the ocean. It sounds like an ancestral dead end but those organic, wet bathmats could be distantly related to humans and their fossils can tell us a lot about evolution.

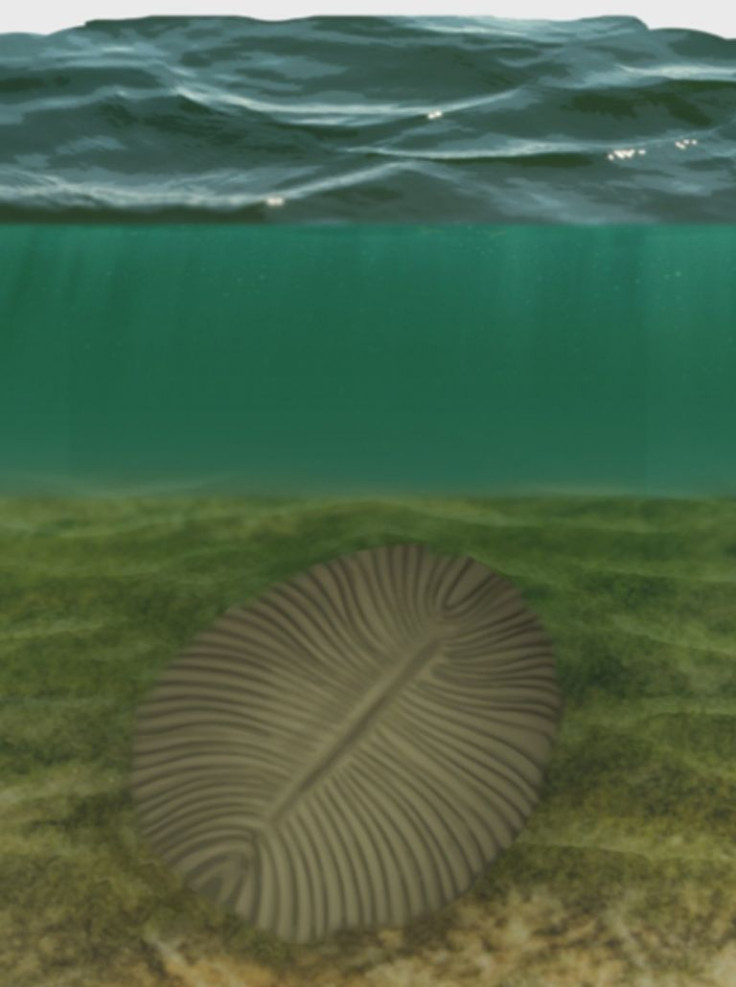

The flat marine animals called Dickinsonia lived more than 550 million years ago, and they were “surprisingly highly regulated,” a study in the journal PLOS One found. Although they’ve classically been hard to categorize in our taxonomy of living creatures, researchers analyzed hundreds of fossils in South Australia, which was submerged during the time of the Dickinsonia, to better understand them. They determined the extinct animals are somewhere between sponges and bilaterians, a popular and diverse group that got its name because of body symmetry.

Read: Earth’s Early Life Formed in Acidic Oceans

Humans are bilaterians, as you can draw a line down the middle of us and our two sides are basically anatomically identical.

Dickinsonia had soft bodies that were flat, oval-shaped and covered in raised strips known as modules. They ate microbes and algae and could be as small as an inch or as large as several feet. Examining their fossils showed they shared a lot with bilaterians, but also didn’t have a mouth or anus, among other differences, so they are unlikely to be related.

“Although we saw some of the hallmark characteristics of bilateral growth and development, we don’t believe Dickinsonia was a precursor to today’s bilaterians, rather that these are two distinct groups that shared a common set of ancestral genes that are present throughout the animal lineage,” researcher Scott Evans said in a statement from the University of California, Riverside. “Dickinsonia most likely represents a separate group of animals that is now extinct, but can tell us a lot about the evolutionary history of animals.”

Part of what makes them so informative is because of how the large marine animals grew up and moved around. The university said they were the first sea creatures to “become large and complex, to move around, and form communities.”

Read: Fossils Found by Accident Show Evolution of Early Marine Life

Their communities thrived on an Earth that was quite different from the planet we know today. For one, research has suggested that early life here formed in seas that were more acidic, with a pH level that was closer to urine or milk than to the more alkaline ocean water you would find now. The more acidic content has roots a few billion years back and the waters changed slowly over time as the sun got brighter and the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere went down. During that gradual change, many life forms came and went, evolving into more complex creatures or instead dying out and becoming just another part of the fossil record. Dickinsonia is just one link in that chain.

“We wanted to know if these creatures were part of a group of animals that survived or a failed evolutionary experiment,” researcher Mary Droser, a paleontology professor at UC Riverside, said in the university statement. “This research adds to our knowledge about these animals and our understanding of life on Earth as an artifact of half a billion years of evolution.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.