France's Reckoning With Colonial Past Reviewed In Algeria Report

A historian tasked by President Emmanuel Macron with assessing how France deals with its colonial past in Algeria -- a hugely sensitive issue six decades after Algerians won independence -- will deliver his recommendations on Wednesday.

The atrocities committed by France in its attempt to quash Algeria's bid for independence, as well as by the nationalists who waged an eight-year liberation war, continue to strain relations between the two countries.

Macron, the first president born after the colonial period, has gone further than any of his predecessors in recognising the scale of abuses by France in the North African country.

While campaigning for president in 2017 he caused a sensation by declaring that the colonization of Algeria was a "crime against humanity."

A year later, he acknowledged that France had instigated a system that facilitated torture during the 1954-1962 Algerian war, which ended 132 years of French rule.

It was a startling admission in a country where the colonization of Algeria was long seen as benign and many are opposed to the idea of repentance.

"In French political culture, anti-colonialism has always been an extremely fringe movement," historian Sylvie Thenault told AFP.

"There is a profound conviction that the French Republic is a force for good that thwarts the possibility of criticizing what is done in the name of the Republic," she added.

No other event in France's colonial history had as deep an impact on the national psyche as the Algerian war.

More than one million French conscripts saw service in the conflict.

After it ended hundreds of thousands of European settlers fled to France, a wrenching exodus that sowed the seeds of lingering anti-Arab sentiment.

Tens of thousands of Algerians who fought alongside French forces also crossed the Mediterranean to escape Algerian nationalist lynch mobs.

On Wednesday, Benjamin Stora, the historian Macron commissioned in July with assessing "the progress made by France on the memory of the colonization of Algeria and the Algerian war," will submit his findings.

Macron is hoping that Stora's report will help normalize relations between France and Algeria, which also appointed an historian to work on the project.

But in a sign of the difficulty of achieving consensus in France on the issue, some MPs went on the attack as soon as Stora had accepted his brief, suggesting that the Algerian-born historian would not be partial.

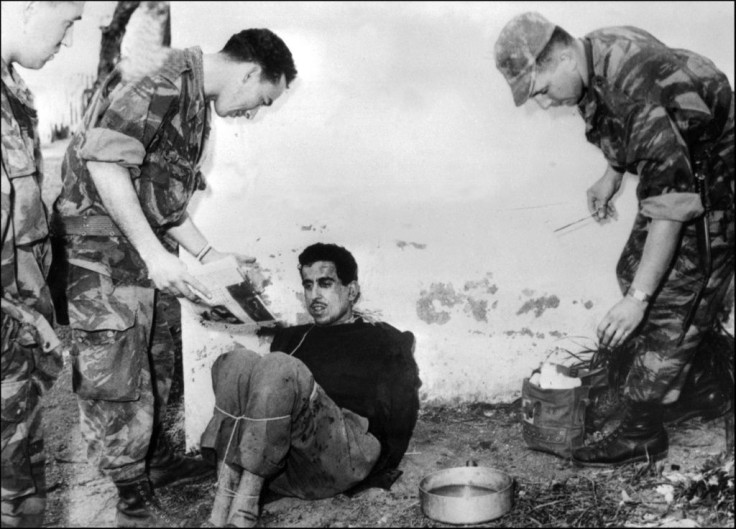

During the war French forces cracked down on independence fighters and sympathisers, and a French general later admitted to the use of torture.

Algerian independence fighters also targeted civilians and mistreated prisoners during a complex conflict characterised by guerrilla warfare, in which hundreds of thousands of Algerians died.

But the many Algerians hoping for an official apology from France risk being disappointed.

Speaking to the Le Soir d'Algerie newspaper, Stora argued that shedding full light on the past was more important that seeking forgiveness.

"In my view, it is more important to continue getting to know what the colonial system entailed in terms of the daily reality, the ideological aims and the French and Algerian resistance to the system," he said.

Thenault agreed.

"It's important that France face up to its colonial past, but the notion of repentance is too religious, too Christian."

France's actions in Algeria left a deep well of bitterness and resentment that has been blamed by some experts for the drift of some second- and third-generation immigrants into extremism.

In a speech in October on combatting radicalisation, Macron acknowledged that France's colonial past and the Algerian war had "fed resentment" against France.

But the decision by wartime president Charles de Gaulle to grant Algeria its independence in 1962 -- a decision ratified by referendum -- also proved divisive, with French nationalists bitterly opposing the move.

As the dust settles on the conflict, French leaders have become bolder about acknowledging wrongdoing in Algeria.

In 1998, Jacques Chirac acknowledged the massacre of civilians in the town of Setif in 1945, and in 2012 Francois Hollande recognised the "suffering" caused by the colonisation.

But atrocities by the military largely remained taboo.

Speaking to Jeune Afrique magazine in November, Macron described France as being "locked in a sort of pendulum between two stances: apologizing and repentance on the one hand and denial and pride on the other.

"As for myself I would like truth and reconciliation," he said.

In 2018, he announced that France would open up its archives on the thousands of civilians and soldiers who went missing during the war, both French and Algerian.

But with many of the files classified state secrets historians complain that access is still heavily restricted.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.