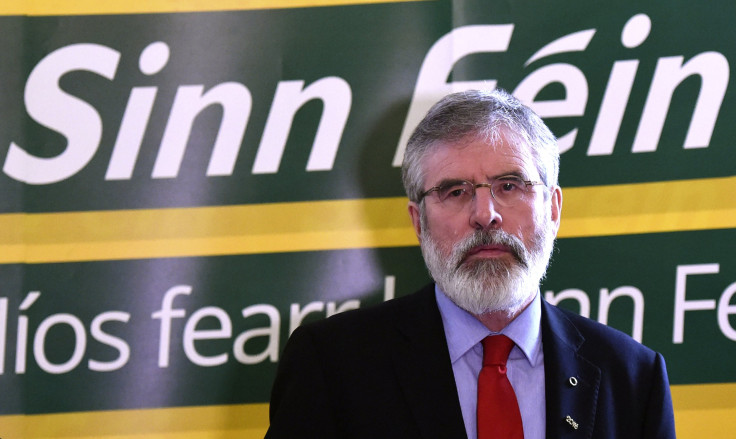

Gerry Adams’ IRA Links Threaten To Derail Sinn Féin Success Ahead Of Irish Election

CORK, Ireland — A century after the Easter Rising, the armed rebellion that marked the beginning of the end of British rule in Ireland, the Irish people are preparing to vote for a new government. One of the most compelling political stories of the last five years has been the rise of Sinn Féin, the republican party with deep ties to the IRA, and its charismatic and controversial leader Gerry Adams — but it’s Adams’ reputed links to the violence that terrorized the country for 30 years that may have scuppered his party’s chances of taking power.

Ireland votes Friday to elect 158 members of Parliament in 40 constituencies across the 26 counties that make up the Republic of Ireland. Sinn Féin, which is part of the government in Northern Ireland, started out its election campaign with the hope of being an integral part of the next government in the South, too.

However, Adams’ inability to relay the details of his party’s policies on taxes, healthcare and the economy, along with a controversial policy to dismantle a court designed for the most serious criminals and his own alleged links to the IRA, have overshadowed any good work being done by his colleagues.

In an opinion poll published days before the election, Sinn Féin’s support had dwindled to 15 percent, down from a high of 20 percent earlier in the campaign. This would make Sinn Féin the third-largest party in Ireland, with both of the bigger parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, ruling out the possibility of entering a coalition with Adams and his colleagues.

At the height of its recent popularity, the party was expected to return 40 members of Parliament. Analysts now expect that figure to be fewer than 30, and while a huge improvement over the 14 members it returned in 2011, many will see this as a lost opportunity.

For those who have not been following Irish politics closely, the rise of Sinn Féin as a mainstream political force may come as somewhat of a surprise, but the party has tapped into a growing resentment among working class people at the bailout of the banks following the economic crash in 2008 and the subsequent austerity-led policies of the ruling government.

According to Eoin O’Broin, a Sinn Féin candidate expected to be elected in Dublin, the reason for the rise in his party’s popularity is that it offers a “distinctive brand and style of politics” at a time when mainstream parties are “increasingly indistinguishable in policy terms.”

Sinn Féin’s grassroots-style politics plays well in working-class areas like Dublin Mid-West where O’Broin is hoping to top the polls, but in other areas of the country, the links to the past remain a barrier that many can’t forget.

Sinn Féin, which translates as “We Ourselves,” was a party founded at the beginning of the 20th century as a way of bringing together disparate Irish nationalist groups that sought to take back control of the country from the British. The party’s identity has formed and reformed over the course of the last century, but in recent times it has been most closely aligned with the fight to create a 32-county Ireland.

The Irish election was called on Feb. 3, and in the three weeks since, it hasn’t been Sinn Féin's policies that have dominated headlines but rather Adams, who has been president of the party for more than 30 years. His position within the party is as strong now as it was when he joined.

Adams has always denied being a member of the IRA, but several paramilitary groups have identified him as the leader of the group during the height of the Troubles. In a documentary about the Sinn Féin president, journalist Vincent Browne said: “He was by far the most important person in the IRA from 1980 onwards.” However Browne, who reiterated his claims during a televised debate last week at which Adams declined to appear, also highlights Adams’ role in bringing peace to the country.

“I don’t think the peace process would have happened at the time it did without him,” Browne said. “I think he was the crucial person in the peace process, more important than [Tony] Blair or [Bill] Clinton or Bertie [Ahern] or anyone else.”

In addition to his alleged links to the murders carried out by the IRA during the Troubles, Adams’ political opponents have also raised a series of other controversies, including his 1972 arrest in the murder of Jean McConville, a Protestant mother of 10, the alleged cover-up of pedophiles within the IRA and more recently his links to Thomas “Slab” Murphy, the former IRA chief of staff convicted of nine counts of tax evasion last year. At the time of his conviction, Adams referred to Murphy as “a good Republican.”

And yet, party members say they don’t feel Adams is a hindrance to its prospects in this election as those who since voters want to talk about other things. “People are much more interested to know what are you doing on tax [policy], what are you doing on education, what are you [doing on] health, so I don’t think the high-wire political battle has as much of an impact as the people involved in that would like it to have,” O’Broin said.

The “high-wire political battle” O’Broin mentioned is the one that has played out on national television and radio and in the opinion pages of Ireland’s national newspapers in the last three weeks. During a trio of televised leaders debates, Adams faced a constant barrage of attacks on his past, as well as accusations he was unable to talk in detail about his party’s tax policies.

In one car-crash radio interview with the national broadcaster, Adams appeared unable to recall his party’s tax policies. During the televised debates, Adams avoided going into detail about Sinn Féin’s policies, instead repeating the refrain “the three amigos” when referring to the leaders of the main political parties, accusing them of leading Ireland into the economic problems it experienced in the last decade.

From Sinn Féin’s point of view, the problem is not with Adams but with a biased and unsympathetic media. To illustrate the problem, O’Broin pointed to an interview carried out with well-known crime journalist Paul Williams a week before the election on “The Late Late Show,” the most-watched show on Irish television.

Williams was speaking about the recent spate of high-profile murders in Dublin related to feuding drugs gangs when he brought up Sinn Féin’s controversial proposal of abolishing the Special Criminal Court, a nonjury court where the most serious crimes are heard. Williams said: “The only people who will vote for Sinn Féin in regard to [abolishing the SCC] are the drug dealers, the killers, the kidnappers and the terrorists.”

“[Williams] deliberately abused his slot on that show to make a very direct attack against Sinn Féin,” O’Broin said. “We just want fair coverage.” Adams and Sinn Féin claim the SCC is undemocratic and people have a right to be tried by a group of their peers, pointing out that other countries have come up with solutions to allow jury trials in even the most serious of cases. Opponents have accused Sinn Féin of seeking the abolition of the SCC because it was where “Slab” Murphy was convicted just months ago.

The electorate will have their say Friday. With as many as 25 percent of voters still undecided, Sinn Féin believes it will make significant gains, and O'Broin says the party is happy to continue to gain momentum even if it’s not happening as fast as some would like, but it will not compromise its beliefs to get into power.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.