Giant Container Ships Arrive On US Shores, But Many Ports Not Prepared For Era Of Megaships

The era of megaships has arrived on U.S. shores. The two largest container ships ever to unload in North America reached Los Angeles in late December, marking a milestone as the global shipping industry increasingly turns to colossal vessels to drive down costs.

The larger of the two ships, the CMS CGM Benjamin Franklin, stretches 1,300 feet — about as long as the Empire State Building is tall. About 1,500 longshoremen spent about 56 hours moving nearly 11,230 containers on and off the ship before the visit ended Dec. 30, the Port of Los Angeles said.

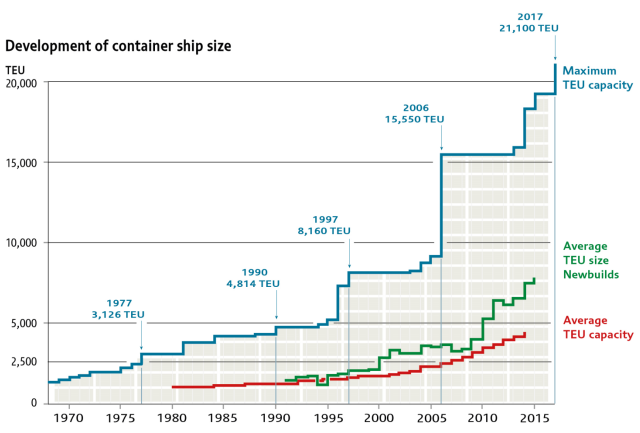

Megaships are designed to move more goods on less fuel, boosting both market share and efficiency for transportation companies. The average container ship being built today is nearly three times the size of the average ship a decade ago, and builders expect ship volumes to keep growing in the next two years.

Yet as the size of cargo ships balloon around the world, North American ports are struggling to catch up.

Many bridges and docks on the West and East coasts are too low or narrow to accommodate the megaships. Logistics teams, labor crews and railroad networks are often too small to handle the sudden glut of containers these ships deliver. While ports in Asia and Europe already work with megaships, U.S. and Canadian ports need to undergo billions of dollars in infrastructure upgrades to meet the mammoth-size demand.

"Everything has been built around what the status quo is now, and you're upping the ante here," Jim Blaeser, a maritime analyst at global consulting firm AlixPartners, told the Los Angeles Times this week.

The Port of Los Angeles is undergoing a $510 million project to expand its cargo-handling capacity at the TraPac terminal. Next door, two Long Beach port terminals are in the midst of a $1.3 billion expansion that will create one of the country's most automated docks. A separate $1.3 billion plan in Long Beach will replace the Gerald Desmond Bridge, which is too low for the megaships expected to arrive in the next five years.

The port of Oakland and ports of Seattle and Tacoma, Washington, also have terminals large enough to accommodate megaships. The Prince Rupert port in British Columbia, Canada, is on track to handle such vessels by 2017, followed by the Port of Vancouver early next decade, the Los Angeles Times reported.

On the U.S. East Coast, port operators are similarly racing to modernize. The Georgia Ports Authority, which owns the Port of Savannah, is spending about $1.5 billion in the next decade to improve crane operations, storage facilities and other infrastructure. The state of Georgia is spending $120 million more to improve roads near the port this year. In New York and New Jersey, the joint port authority is carrying out a more than $1 billion plan to raise the Bayonne Bridge connecting Staten Island and New Jersey to allow for taller vessels.

As the world shifts toward bigger ships, however, some transportation experts have questioned whether the megaships are worth the hassle.

The foremost challenge with giant ships is that supply far outstrips demand. Analysts at Moody's Investors Service estimated while global container ship capacity would grow up to 10 percent through the end of 2015, demand would grow only about 4 percent, according to a November report.

"The growth of containerized seaborne trade is no longer in line with the growth of the world container fleet," Olaf Merk, administrator of ports and shipping at the OECD's International Transport Forum, said on a economic policy blog. "We found a disconnect between what is going on in the boardrooms of shipping lines and the real world."

If shipping companies aren't filling up these megaships, then the savings per each transported container declines, Merk and his colleagues found in a June 2015 report on megaships. At the same time, the cost of operating and accommodating these giant ships is substantial.

Expanding infrastructure and upgrading ports to cater to bigger ships could amount to roughly $400 million in additional annual transportation costs, the report said. About a third of those extra costs might be related to equipment, another third to dredging, and a final third to port infrastructure and surrounding facilities.

The ships themselves carry extra expenses. Megaships stay on average 20 percent longer in ports than conventional ships, requiring port authorities to spend more time and provide more services to accommodate the longer-staying vessels, Merk said. Insuring and salvaging unprecedented loads of cargo is another strain for operators. And congestion at ports is already rising as trucks and trains scramble to load and offload tens of thousands of containers at a time.

Still, Merk said megaships — which account for about an eighth of the total global shipping fleet — will soon become the new normal for many major ports around the world.

"One thing is sure: this will lead us to a decade of port gridlock if nothing is done," he wrote.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.