Global Employment Crisis Deepening, Equivalent Of 400 Mn Jobs Lost: UN

The coronavirus crisis has taken a much heavier toll on jobs than previously feared, the UN said Tuesday, warning that the situation in the Americas was particularly dire.

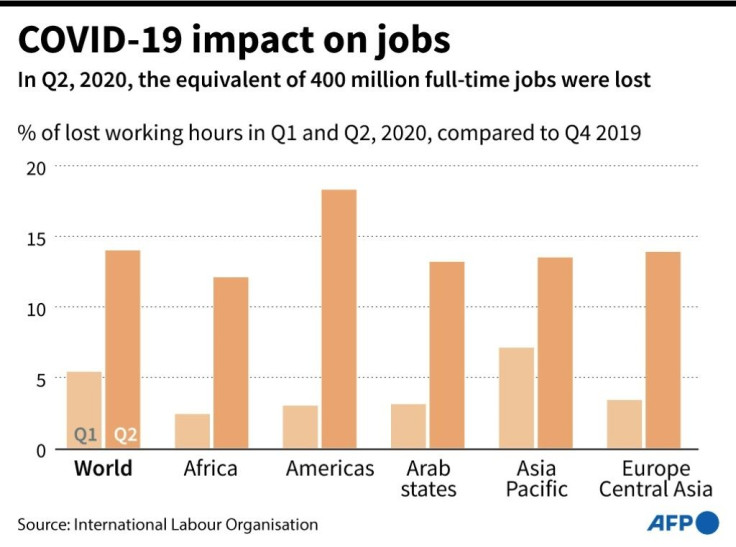

In a fresh study, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated that by the mid-year point, global working hours were down 14 percent compared to last December -- equivalent to some 400 million full-time jobs.

That is more than double the number forecast by the UN organisation back in April, when it expected 6.7 percent of working hours to be lost by the end of the second three-month period of the year.

It is also far higher than the ILO estimate in late May, when it expected 10.7 percent of global working hours to vanish during the period.

"Things are getting worse. The job crisis is deepening," ILO chief Guy Ryder told AFP in an interview.

"We are not through this yet," he warned.

The ILO said the new figures reflected the worsening situation in many regions in recent weeks, especially in developing economies.

Its report pointed out that 93 percent of the world's workers live in countries still affected by some sort of workplace closures, with the Americas experiencing the greatest restrictions.

The United States and Latin America are currently the areas hardest-hit by the pandemic, which has killed more than 500,000 people worldwide and infected more than 10 million.

Soaring transmission rates in the United States, which alone accounts for a quarter of all infections and deaths globally, and in countries like Brazil, which accounts more than 1.3 million cases, have hit the labour market hard.

The crisis is "hitting particularly hard the Americas, where we see the loss of jobs as being the worst in the world," Ryder said.

Overall, the Americas lost over 18 percent of working hours during the second quarter, equivalent to 70 million full-time jobs, the ILO said.

South America has shed a full 20.6 percent of all working hours, while North America has seen its working hours dip 15.3 percent, the study found.

By comparison Europe, the Arab states, and most of Asia saw working hours dwindle by around 13 percent, while they fell just over 12 percent in Africa.

The crisis had also hit women harder, threatening decades of progress, said Ryder.

Women are more likely to be in the sectors most affected by the crisis and they also bear most of the additional burden brought on by closures of schools and care facilities.

"All the evidence is that women are being hit harder than men," he said -- and the crisis risked aggravating gender inequalities in the workplace.

"The stumbling, slow and glacial gains made towards gender equality in recent decades runs the risk of simply being sent into reverse."

The ILO painted three possible scenarios for the second half of the year, but Ryder acknowledged "we cannot see a scenario in which we get back to the starting pont with which we began the year."

The most pessimistic scenarios assumes a second wave of the pandemic that significantly slows recovery. Global working hours would still be 11.9 percent (the equivalent of 390 million jobs) lower at year-end than at the end of 2019, the study said.

The most optimistic scenario, which assumes a rapid recovery, would still see a 1.2-percent year-on-year loss of global working hours -- equivalent to 34 million jobs.

That is "still a very, very hard hit on the global economy", Ryder said.

He called on countries to work together to implement the policies needed to help workers and "build back better".

"The decisions we adopt now will echo in the years to come and beyond 2030," he said.

"I remain hopeful that because of the obvious and stark need of international cooperation, the world in some way will recover its appetite for multilateral cooperation," he said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.