Global Slowdown Fears Spark Flight To Safety As Stock Outflows Hit 15-week High of $8.3B

Fears of global economic downturn drove investors towards safe-haven assets this month, including money-market funds and treasuries, after equity outflows hit a 15-week high of $8.3 billion last week, Bank of America Merrill Lynch said Friday. This marked seven straight weeks of inflows to government bond funds, the longest inflow streak since November 2012, and three straight weeks of inflows to money-market funds ($8.2 billion), the longest inflow streak since November 2014, the firm said.

The moves come in the midst of a global stock market sell off, in which the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted more than 1,000 points for the week, slipping into correction territory for the first time since 2011. Stock markets across the U.S., Asia and Europe faced multiple bouts of volatility Friday after China revealed new evidence of a sharper-than-expected economic slowdown.

Early Monday, the rout appeared ready to continue into the new trading week. U.S. stock futures traded sharply lower Monday, with Dow futures plunging more than 400 points, as fears regarding the health of China's economy escalated across global markets. All major European indexes traded down and China’s benchmark Shanghai Composite recorded its biggest one-day percentage loss since 2007, closing down 8.5 percent.

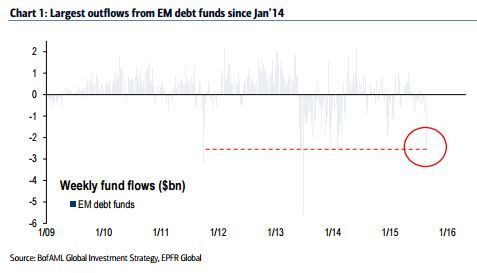

Fears of stagnating growth sent investors to safe-haven assets, with $2.5 billion flowing into funds devoted to government bonds and Treasurys, Bank of America Merrill Lynch data showed. Around $6 billion flowed out of Emerging Market equity funds last week, marking its highest weekly total in five weeks. Emerging debt funds lost $2.5 billion, their biggest weekly loss since January 2014.

Nigel Green, CEO of deVere Group, a financial advisory firm that consults on more than $10 billion in assets, says growing anticipation of rising U.S. interest rates this year also added to investor uncertainty.

Most economists had expected the U.S. Federal Reserve to raise interest rates as early as September, but an increasing number of experts now say it's possible the Fed is rethinking its plan.

China, the world’s second-largest economy, unexpectedly devalued the yuan two weeks ago in an attempt to jumpstart its flagging economy. The country’s benchmark Shanghai Composite has also lost around 30 percent of its value from its peak in mid-June.

“Investors are spooked and stock markets are tumbling in response,” Green said in a note. “I believe that this volatility is likely to remain with us, at least until the end of the year. By then we will have a clearer view as to the risk of a China economic ‘hard landing,’ and the degree to which capital markets are prepared to absorb higher U.S. interest rates.”

The yield on the U.S. 10-year Treasury slid further last week to 2.045 percent Friday from 2.084 Thursday. The benchmark 10-year Treasury note ended 2014 at a yield of 2.17 percent, and the yield had drifted lower from late 2013, when it touched 3 percent.

“The declining trend continued into early January as signs of economic weakness became more apparent,” the American Institute for Economic Research said it its monthly business conditions report in August.

The 10-year note’s yield hit a 2015 low in late January and then went on a roller-coaster ride trending higher, settling in a range of 2.2 percent–2.5 percent for June that continued into July.

However, yields have decline further this month amid growing uncertainty about global economic growth.

The 10-year acts as a barometer of where the U.S. and global economies are headed. A low Treasury yield generally means investors foresee tepid inflation. When investor confidence is high, the price of the 10-year Treasury bond falls and yields go higher because market professionals expect to find a high return on investments. However, when confidence is low, the price on the 10-year goes up as there is more demand for Treasurys as a safe investment, and yields subsequently fall.

Minutes from the Fed’s July meeting, released last week, indicated conditions for the first rate increase in nearly a decade had not been met, due primarily to muted price increases. U.S. inflation has run below the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target for 38 straight months.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.