The Golden Mile: Could Leicester, The Most Ethnically Diverse Place In Britain, Become UK’s First Asian-Majority City?

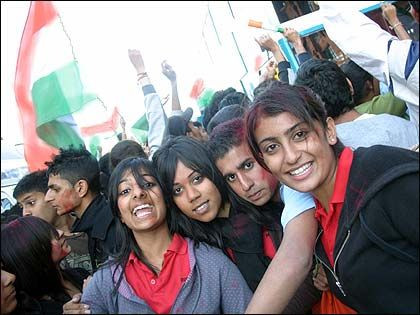

If any one city in the United Kingdom exemplifies how mass immigration has created a multi-ethnic and multiracial modern British society, it may be the town of Leicester in the East Midlands. So many people from the far-flung corners of the former British Empire and elsewhere have migrated to Leicester over the past half-century that by 2012, ethnic people accounted for a majority of the city’s population of some 330,000 residents.

In January 2013, the Daily Telegraph newspaper reported that in Leicester (along with Luton and Slough), white Britons were in the minority, having slipped below the 50 percent mark in terms of their overall population representation. Indeed, as of the 2011 U.K. Census, white Britons accounted for 45.1 percent of Leicester’s population (down from 61 percent in 2001), while Asian Indians (including British-born Indians) accounted for 28.3 percent of the population – up from about 26 percent in 2001.

In the northeastern quarter of Leicester, more than half (55.3 percent) of the population are now Indian or Pakistani, while 39 percent and 17.2 percent of the residents are Hindu and Muslim, respectively. In the east of Leicester, Indians account for nearly half (46.9 percent) of the community, with Muslims and Hindus forming a majority of the population.

The individual districts of Leicester with the highest Indian presence comprised Latimer (79.2 percent of the local populace), Belgrave (65 percent), Spinney Hills (60.2 percent), Rushey Mead (54.7 percent), Coleman (54.4 percent), Stoneygate (42.3 percent), Evington (42.2 percent), and Charnwood (42.1 percent). The aforementioned neighborhoods are generally clustered in the northern and eastern parts of the city, whereas whites are concentrated in the western and southern regions.

Overall, Leicester has the highest proportion of Asian Indians or British Asians anywhere in Britain, where – on a national basis -- they account for only about 2.6 percent of the total population. (In fact, Leicester's Asian community is so large and influential that the city now hosts the biggest Diwali – i.e., the Hindu festival of lights holiday – celebrations outside of India.) Nearly half (49 percent) of Leicester’s population comprise people who trace their ancestry to Asia, Africa, the Caribbean or are of mixed-race background. Another 5 percent of Leicester residents are white, but not British, principally from Ireland or Eastern Europe.

Interestingly, the 2011 Census report also noted that a large portion of the nonwhite (or non-Briton) population of Leicester considered themselves “British” first above all else. “We already know from other sources that British identity is felt at least as strongly by those of minority ethnicity as those of white British ethnicity. This is the case for people of similar age and background born in the U.K.,” the report stated.

The Leicester Mercury newspaper reported upon release of the census report that the city’s mayor, Sir Peter Soulsby, praised the community’s high level of diversity, calling it a “a great strength.” "I think you will find a large proportion of people who, for instance, might say they are ‘Asian’ will actually be Leicester-born and bred," he quipped.

Along with changes in race and ethnicity, Leicester has also witnessed a dramatic alteration in its religious profile. Between 2001 and 2011, the percentage of residents who professed to be Christians dropped from 45 to 33 (which still ranked it as the No. 1 faith, however). Part of this decline could be attributed to a significant portion of the city – 23 percent -- who say they adhere to no organized religion, up from 17 percent in 2001. Separately, fully 18.6 percent and 15.2 percent of Leicester residents are Muslim and Hindu, respectively, with smaller numbers of Sikhs. "I think we are seeing what makes Leicester so unique – there is no such thing as a majority,” Suleman Nagdi, chairman of the Federation of Muslim Organisations, told the Mercury. "I think it shows we need to keep working hard to keep our [inter-ethnic and inter-faith] relationships going."

How and why did so many Asian Indians migrate to Leicester? Following the end of World War II, Great Britain faced a severe labor shortage – consequently, industries, with the support of the government, encouraged people from across the British Commonwealth to move to the United Kingdom where jobs in factories, foundries, public transport and other businesses were plentiful.

In 1948, the British government passed The Nationality Act, a law that essentially allowed Commonwealth citizens the right to move to the "mother country," Great Britain. Initially, tens of thousands of migrants – mostly men -- from India and Pakistan moved to England, particularly to London, but also to the old industrial and mill towns of the Midlands and the North, especially Birmingham, Manchester, Bradford and Leicester, among others.

Uday Dholakia, chairman of the Leicestershire Asian Business Association (LABA), said that during the 1950s and 1960s, Indians and Pakistanis poured into Leicester to work in the textile industry, which existed then. After these overworked, underpaid men settled down and purchased homes, they subsequently brought over their families, wives and children. In Leicester itself, cheap private housing soon turned the Spinney Hills and Belgrave neighborhoods into Indo-Pakistani enclaves in less than a generation.

The arrival of mostly Gujarati Indians in the early 1970s marked an important milestone in Leicester's postwar immigration history. This particular wave did not come from India, but rather from Uganda in East Africa, where in 1972 then-President Idi Amin ordered the deportation of the country's 90,000 Asians (most of whom were Gujaratis). A similar, but smaller, exodus occurred earlier in 1968, when another East African state, Kenya, expelled some of its Asians – many of whom also migrated to the U.K.

These episodes sparked much alarm and indignation in Britain – particularly since many Asians in East Africa carried U.K. passports, granting them the right to legally settle in England. In Leicester itself, the city council placed advertisements in Ugandan newspapers warning the local Asian community that the city had no jobs or housing for them, thereby discouraging their arrival. The Council accurately feared that many Ugandan Asians would choose to move to Leicester, since other East African Asians had already settled in the town. (Dholakia noted that a few years ago the Leicester City Council admitted it was wrong to discourage the influx of East African Asians and apologized. Last year, the council even honored their arrival by mounting a special exhibition to remind people of the turmoil from that period and how it was overcome).

Colin Hyde, of the East Midlands Oral History Archive at the Centre for Urban History at the University of Leicester, indicated that after the Ugandan Asian exodus of 1972, the extreme right-wing, anti-immigrant National Front party stepped up its activities in Leicester. “However, the National Front imploded in the late 1970s and the [Leicester City] Council became more proactive in dealing sympathetically with ethnic minorities, and Leicester has been relatively harmonious since,” Hyde said.

Indeed, between 1968 and 1978, Leicester received at least 20,000 Asians from East Africa, settling mostly in Belgrave, Rushey Mead and Melton Road (now the heavily Indian Golden Mile of jewelry shops, cinemas and restaurants). That influx was so large and quick, that East African Asians now comprise the biggest segment of Leicester's Asian community. By 1981, Leicester's Asian population (including Pakistanis and Bangladeshis) approached 60,000 – and now exceeds 100,000. The Asian Indian presence in Leicester is particularly striking, when considering that for the East Midlands as a whole, Indians represent just 3.7 percent of the population.

An article in India's Deccan Herald newspaper from as recently as 2006 marveled over how some parts of Leicester are virtually indistinguishable from the India of the recent past: “The surprise package are the women who came to Leicester in the [nineteen] sixties and [nineteen] seventies, at the tender ages of sixteen or seventeen. Married to men they had never seen before, they have stayed there ever since without losing any of their Indian identity. Like cultural fossils, they are preserved slices of an India of the seventies. The smells of Indian spices waft out of their kitchen windows still, they are not very comfortable with English, their sarees are worn with the careless abandon of women who have worn them day and night, over decades. The world has actually become a global village but what’s fascinating about Indians is that wherever they go they take with them a baggage of beliefs and culture that refuses to be set aside.”

The Asian Indians' numerical strength and economic influence in Leicester has translated into political power. Of the 55 councilors in Leicester's current municipal government, 20 hail from South Asian origins. One of them, India-born Mustafa Kamal, currently serves as the Lord Mayor, a ceremonial position. Dholakia of LABA further noted that two current councilors, Piara Singh Clair and Manjula Sood, both served as former Lords Mayor. In addition, the late Councilor Gordhan Parmar was the first British-Asian Lord Mayor (elected by Council in 1987), followed by the late Councilor Ramnik Kavia. Also, Leicester is an overwhelming Labour stronghold – the party holds 53 of the council's seats, including those of all the Asian lawmakers.

Indians in Leicester also wield significant economic power – there are now at least 3,000 small- and mid-sized businesses owned by Asians in the city. Dholakia said that Indians are now found in a wide array of businesses, including retail, textiles, food and drink manufacturing and service industries. Moreover, Dholakia noted that Leicester’s entrepreneurial spirit helped weather the economic recession of 2007-2008 quite well, particularly through an explosion of retail and food and drink manufacturing which created new jobs. “Food and snacks manufactured in Leicester are exported to the USA and India,” he added.

The Reporter, the staff newsletter of the University of Leeds, said in a report that Leicester is regarded as a successful model of multiculturalism, citing its “prosperous economy” and the “good relations” which exist between communities in what is the “most religiously diverse [British] city” outside London. “This is in part due to the entrepreneurial and social skills of the generally middle class and educated Indian (mainly Gujarati) migrants,” the Leeds publication read. “Those who had already lived alongside people of different faiths in the East African diaspora also brought a commitment to multiculturalism with them.”

In the United States during the 1960s and 1970s, the movement of black and Hispanics into urban neighborhoods sparked a phenomenon known as white flight, in which many white residents in cities like New York, Philadelphia, Chicago and elsewhere flocked to the suburbs, creating instant new white towns outside the urban environment. Something somewhat similar happened in Leicester, with some important differences. Hyde points out that in the 1960s and 1970s, many poor and working-class white residents of Leicester were forcibly moved out of inner-city areas into suburban estates (housing projects) as a result of the government's slum clearance endeavors, not necessarily entirely due to white flight.

Interestingly, many wealthy Asians in Leicester have also joined the white flight, moving to the affluent southern suburb of Oadby, which now has a very large Indian community. But Dholakia points out that there is little suburban space for anyone to “flee” to within the Leicester City Council boundaries. “If you were to look at the affluent area of Oadby, where I live, immediately south, there is a substantial Asian-heritage population,” he said. “[But] the city overall has a mixed and harmonious housing. Young indigenous couples are happy to set up homes in city to benefit [from] a metropolitan lifestyle.” He added that movement away from the small houses in the inner-city to larger homes in the suburbs is more a phenomenon of income, wealth and family size. “You are thinking of the entrenched discrimination of American cities – [but] Leicester is not Detroit,” Dholakia explained. “The urban and suburban neighborhoods [here] have a mixed community. The movement is often driven by access to schools.”

Dholakia also asserts that Leicester is largely free of the racial strife that once engulfed many British cities during the 1970s and 1980s and remains problem in some parts of contemporary Britain. He noted that when the English Defense League, a new British nationalist group that focuses particular ire on Muslims, came to the city in the last few years they were opposed politically and by the people of Leicester. “Strong community cohesion has enabled Leicester to jointly overcome external demonstrations and marches,” Dholakia added.

Despite the large Indian community now in Leicester, Hyde does not believe that Leicester will become an ‘Asian-majority’ town anytime soon. “The city is simply too diverse for that to happen,” he said. “Yes, there’s a sizable Indian population in the city, but there are also significant groups from the Caribbean and Africa, and growing Eastern European communities as well.”

Meanwhile, Dholakia holds up Leicester as a paragon of inter-ethnic cooperation and benevolence. “Leicester has been blessed with high-caliber political and community leadership that works well with all authorities and the police,” he said. “Any short-term conflict and challenges are ironed out quickly. Overall, we have international reputation as a harmonious multi-ethnic communities.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.