Gordon Brown’s School Days: Actually, Pakistan’s Literacy Rate Has Been Improving, With One Glittering Model Of Excellence

Gordon Brown, the former British prime minister and current United Nations special envoy for global education, has unveiled a two-pronged attack to combat some of Pakistan's most intractable social ills: illiteracy and child marriage. At an education conference in the capital city of Islamabad over the weekend, Brown announced that international donors, including Saudi Arabia, United Nations, among others, have pledged $1 billion over the next three years to send millions of illiterate Pakistani youths above the age of 10 to school.

This measure followed a move by the Pakistan government to increase its education budget to 4 percent of GDP by 2018 from the present 2.2 percent level (India currently spends about 3.2 percent of GDP on education). The new cash infusion would be used to construct school buildings, purchase equipment and train school teachers. “I am here to promote and implement plan for universal education in Pakistan,” Brown said at the conference. “There are 7 million children who are out of [school] in Pakistan.” Also, given that Pakistan's illiterate population is disproportionately female and rural-based, Brown further said he is committed to wiping out the ancient custom of child marriage as well as the gender inequality that pervades the countryside.

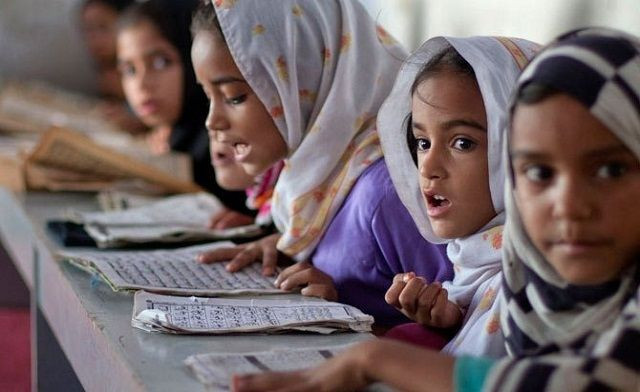

However, despite Brown’s entreaties, Pakistan has actually made tremendous progress in easing illiteracy, even with rapid population growth, partly due to local initiatives, especially in urban areas. According to statistics from The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), as of 2012, 61 percent of young Pakistani females (between the ages of 15 and 24) could read and write, versus 79 percent of males in that age bracket. By 2015, these figures are projected to rise to 72 percent and 82 percent, respectively. Literacy rates for older Pakistanis decline with higher age brackets, with females accounting for a disproportionate number of the illiterate. According to UNESCO, of the nearly 50 million illiterate adults in Pakistan, more than two-thirds are estimated to be female.

For the entire population, by 2015, Pakistan is expected to have a total literacy rate of 60 percent -- well below the 71 percent mark for India, but similar to the 61 percent figure projected for Bangladesh, an equally poor Muslim-dominated state. Overall, literacy rates have climbed steadily across South Asia over the past few decades – consider that as recently as 1998, less than half (about 43.9 percent) of all Pakistanis were literate, while in 1981, a little more than one-quarter of the populace could read and write.

But Brown is correct to point out that significant advances must still be made in Pakistan, particularly with respect to women and girls in rural regions, where millions of females do not even attend school. For example, in Swat, the northwestern region that is home to now world-famous education activist Malala Yousafzai, one-third of the local girls still do not even go to school – partly due to conservative strictures, and lack of educational facilities. “We must develop concerted measurers to send girl and boys to schools. We hope to develop new proposals to speed up efforts to offer education to every child,” Brown said at the weekend conference, after having met with Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, Finance Minister Ishaq Dar and education ministers of all the country’s provinces. “This is movement of change, this is [a] civil rights struggle for change … and girls particularly are demanding their right for education.”

Further, Brown tied the issue of youth female illiteracy with ancient customs that deprive girls and women from ever advancing toward education and work. "As part of our campaign to get every child at school, we want to remind people that the world does not want girls to be married as girls, as brides when they should be at school," he told BBC. "I think that people are realizing that it is unfair for a girl to be pushed into marriage when she's still a child.”

Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif also highlighted the urgency of increasing literacy among the country’s huge youthful population and creating a “knowledge-based” economy that can compete in the global marketplace, particularly in the areas of science of technology. “For Pakistan, education [is] not merely a matter of priority, but, it is the future of Pakistan, which lies in its educated youth,” Sharif said, reported Pakistan’s GEO broadcaster. “More than half of the country’s population is below 25 years of age. With proper education and training, this huge reservoir of human capital can offer us an edge in the race for growth and prosperity in the age of globalization. Without education, this resource can turn into a burden.”

Educating Pakistan’s rapidly increasing population will be a challenge and a strain on finances – but both Nawaz Sharif and Gordon Brown might look to a surprising corner of Pakistan that has somehow achieved almost universal illiteracy and high gender equality. In the remote Hunza Valley, a region in the Gilgit–Baltistan territory of northernmost Pakistan -- reportedly the inspiration for the paradise of "Shangri La" in the book "Lost Horizons" by James Hilton – at least 75 percent of all residents are literate, while virtually all youths, regardless of gender, can read and write. Almost every child in Hunza attends school up to at least the high school level, while many pursue higher studies at colleges in Pakistan and abroad.

Dawn, an English-language Pakistani newspaper, reported that one of the principal factors behind Hunza's stupendous literacy figures trace back to the educational advocacy efforts of the Aga Khan III, Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah. In the early part of the 20th century, he persuaded the mirs [rulers] of Hunza state to educate their people. By 1946, 16 "Diamond Jubilee" schools were established in the Valley, followed by a decision from the Pakistani government to open up public schools in the northern regions, including Hunza. In 1983, Prince Shah Karim Al Hussaini, the Aga Khan IV, introduced The Academy, a high-quality school (including dormitory facilities) exclusively for girls in Hunza. By the early 1990s, the government created “community schools” in Hunza, including the Al-Amyn Model School in the village of Gulmit, which allowed the students' families to participate in lessons.

Two other major developments in regional education gains included the establishment of the Karakoram University in Gilgit, and the founding of organizations by the Aga Khan dynasty that encourage universal education, training and scholarships. The present Aga Khan has also financed local agricultural and other economic endeavors through the Aga Khan Development Network. “There seems to be urgency in terms of acquiring education,” wrote Dr. Shahid Siddiqui, director of the Centre for Humanities and Social Sciences at the Lahore School of Economics, in an article in Dawn. “Parents in Hunza are convinced that the best thing they can do for their children is to help them get a good education. There is a growing interest in higher education for girls.” Siddiqui also emphasized that parents in Hunza encourage their daughters to gain an education and are even willing to send girls to all parts of Pakistan to obtain a quality degree, in dramatic contrast to the behavior of most other parents in the country who keep their daughters under tight control at home.

Friday Times, an independent Pakistani newsweekly, described Hunza as “an oasis of education.” Janeha Hussain in the Times wrote that education and the attainment of knowledge are given top priority in the Valley. “Boys and girls alike approach their schooling with endearing exuberance,” Hussain wrote. “They can be seen walking along the roadside, lunchboxes swinging on their arms and books hugged closely to their chests.” Even more extraordinary, Hussain indicated, the importance of education in this Valley has raised the status of women to equality with men. She cited that in Hunza, “women and girls stroll the bazaars after dusk without male relatives, and no one dares to bat even an eyelash at them, let alone stare sleazily and make risqué comments as is tradition elsewhere.” Women have also become an “integral part” of the local economy, including those who weave Hunza's famous handicrafts.

Hunza differs from the rest of Pakistan in other ways too: The majority of the people there follow Shia Islam, and many are Ismaili Shia Muslims, followers of His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan. (Most other Pakistanis adhere to Sunni Islam.) Also, although most people in Hunza understand Urdu, the national tongue of Pakistan, the primary languages in Hunza comprise Shina, Burushaski, Wakhi among others.

Syed Irfan Ashraf, a Pakistani-based journalist, said in an interview that since the people of Hunza belong to a religious minority, education is their main support system that is required for social mobilization. “Luckily, the Aga Khan Foundation has done enough to set up an infrastructure of schools and colleges,” he said. “Otherwise, this part of the country would have been totally ignored.” Although some of the remote mountainous regions of northern and northwestern Pakistan have been scarred by militant fundamentalism and terrorism, Hunza has largely avoided such associations. Ashraf explained that groups like the Taliban or Lashkar-e-Taiba do not have a strong presence in Hunza, but he contended that such militants do exist in the nearby Gilgit and Chilas regions and could potentially reach the Valley to disrupt the law-and-order situation there. “But people in Hunza valley are peace-loving [and] usually avoid becoming part of any extremist ideology,” Ashraf said. “Similarly, they have so far successfully discouraged extremist religious groups from spreading their influence to Hunza.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.