Green-Glowing Cats Are New Tool in AIDS Research

U.S. scientists have developed a strain of green-glowing cats with cells that resist infection from a virus that causes feline AIDS, a finding that may help prevent the disease in cats and advance AIDS research in people.

The study, published on Sunday in the journal Nature Methods, involved inserting monkey genes that block the virus into feline eggs, or oocytes, before they are fertilized.

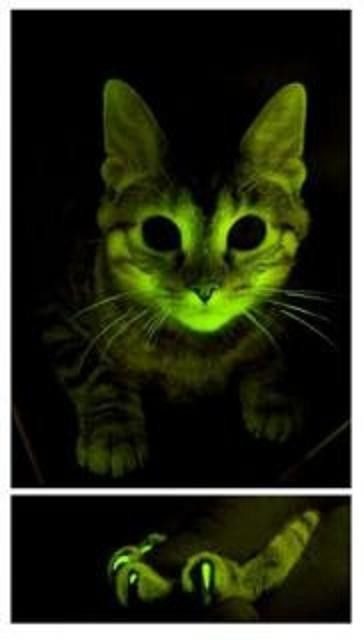

The scientists also inserted jellyfish genes that make the modified cells glow an eerie green color -- making the altered genes easy to spot.

Tests on cells taken from the cats show they are resistant to feline immunodeficiency virus, or FIV, which causes AIDS in cats.

This provides the unprecedented capability to study the effects of giving AIDS-protection genes into an AIDS-vulnerable animal, Dr. Eric Poeschla of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who led the study, said in a telephone interview.

Poeschla said that besides people, cats and to some extent, chimpanzees, are the only mammals that develop a naturally occurring virus that causes AIDS.

Cats suffer from this all over the world, he said.

Just as the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, does in people, FIV works by wiping out infection-fighting T-cells.

FIV infects mostly feral cats, of which there are half billion in the world, Poeschla said. It is transmitted by biting, largely by males defending their territory, but companion cats are affected as well.

In both humans and cats, proteins called restriction factors that normally fight off viral infections are defenseless against HIV and FIV because the viruses evolved potent counter-weapons. But certain monkey versions of these restriction factors are capable of fighting the virus and the team used one such gene from the rhesus monkey.

For the team, which included collaborators in Japan, the trick was to get the monkey gene for the restriction factor -- known as TRIMCyp -- into cats to block cells from becoming infected with the virus.

GREEN FLUORESCENT PROTEIN GENE

To do that, they used a harmless virus to insert the genes into the eggs, a process that has already been done in other mammals including mice, pigs, sheep and marmoset monkeys.

To make it easier to check which cells had the monkey gene, the team also inserted a green fluorescent protein gene from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria that makes them glow green.

We did it to mark cells easily just by looking under the microscope or shining a light on the animal.

The method worked so well nearly all offspring from the modified eggs have the restriction factor genes. And these defense proteins are made throughout the cat's body.

The team has mated two of the three original green-glowing cats, which have produced litters totaling eight kittens which make glowing cells as well.

But the point is not to breed generations of disease-resistant, glowing cats. Rather, the team plans to study these felines as a new way to develop treatments for HIV and the feline version of the disease.

Researchers said the work has several potential uses.

This technology can be applied to a wide range of species, for many of which there are clear applications and potential benefits, Dr. Laurence Tiley of the University of Cambridge said in a statement.

It will be interesting to see how enthusiastically this capability in cats is received and adopted by the HIV and neurobiological research communities and what other research opportunities it offers. A representative non-primate animal model would be a fantastic new tool for studying HIV pathogenesis.

So far, Poeschla's team has only tested cells taken from the animals and found they were resistant to FIV. But eventually they plan to expose the cats to the virus and see if they are protected.

If you could show that you confer protection to these animals, it would give us a lot of information about protecting humans, Poeschla said.

For cats, this may eventually lead to gene therapy or new drug treatments for FIV, he said.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.