Haiti PM Agrees To Leave In Regional Push To End Crisis

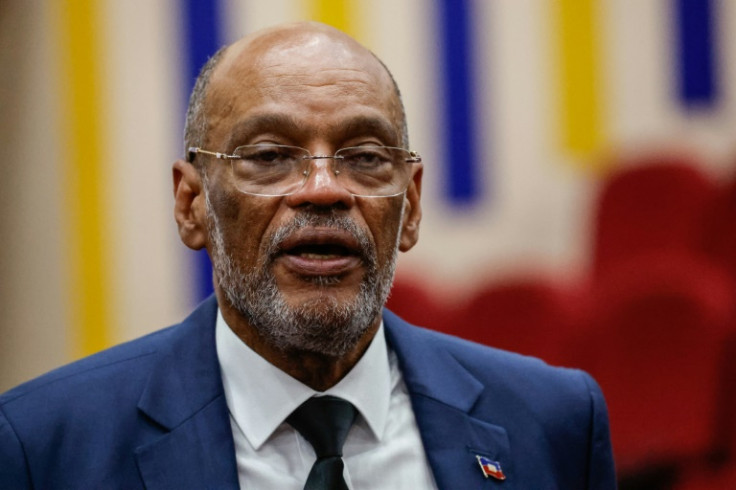

Haiti's prime minister agreed late Monday to step aside as armed gangs plunge his country into anarchy, as he accepted a regional push for a transition that sets the stage for international intervention.

Caribbean nations secured Ariel Henry's resignation at an emergency meeting in Jamaica where US Secretary of State Antony Blinken offered another $100 million to pave the way for the security force, which will be led by Kenya.

Gangs have taken over much of the Western Hemisphere's poorest country and in recent weeks the crisis has grown even more violent, with bodies strewn across the streets, armed bandits looting basic infrastructure and fears rising of a famine.

"The government I lead cannot remain insensitive to this situation. As I have always said, no sacrifice is too great for our homeland Haiti," Henry said in a resignation address that he posted online.

Gang leaders had demanded the departure of Henry who, while speaking of himself as a transitional figure, had remained in power since 2021 when Haiti's president was assassinated. Haiti has not held an election since 2016.

Guyana's President Irfaan Ali, who chairs the Caribbean regional body CARICOM, announced after a weekend of diplomacy that Henry would leave once a new transitional authority is in place.

Ali saluted Henry, saying that the prime minister -- stranded in Puerto Rico as Haiti's main airport is no longer functioning -- "has assured us in his actions, in his words, of his selfless intent."

"And that selfless intent was to see Haiti succeed," Ali said.

Blinken, who spent seven hours inside the talks in a Kingston hotel, confirmed Henry's resignation in a telephone call initiated by the prime minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley.

A US official traveling with Blinken said that Henry had agreed to quit on Friday but was waiting for the Kingston conference to sort out details of the transition.

Also raised were ways to prevent reprisals against Henry and his allies, with the United States agreeing that the outgoing prime minister would be welcome to stay on US soil if he feels unsafe in Haiti, the official said.

Senior officials from Brazil, Canada, France and Mexico joined the talks. CARICOM, in a statement with its partners and the United Nations, said that Haiti's new Transitional Presidential Council would have seven voting members who make decisions by a majority vote.

The seven will include representatives of major political parties, the private sector and the Montana Group, a civil society coalition that had proposed an interim government in 2021 after President Jovenel Moise's assassination.

There will also be two non-voting seats on the council -- one for civil society and another for the church.

Authority has badly eroded in Haiti. A nighttime curfew was extended through Thursday -- although it is unlikely overstretched police can enforce it.

Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness, the host of the crisis talks, warned that Haiti risked all-out civil war.

"It is clear that Haiti is now at a tipping point," he said, urging "strong and decisive action" to "stem the sea of lawlessness and hopelessness before it is too late."

Blinken promised another $100 million to back an international stabilization force, bringing the total pledged by the United States to $300 million since the crisis intensified several years ago.

Blinken also offered another $33 million in immediate humanitarian assistance.

Escalating violence "creates an untenable situation for the Haitian people, and we all know that urgent action is needed on both the political and security tracks," Blinken said.

"All of us know that only the Haitian people can, and only the Haitian people should, determine their own future -- not anyone else," Blinken said.

But he said the United States and its partners "can help restore foundational security" and address "the tremendous suffering" in Haiti.

President Joe Biden -- who ended the US war in Afghanistan -- has ruled out putting troops in harm's way in Haiti, which the United States occupied for nearly two decades a century ago and where it has intervened since.

Eyes initially turned to Canada, but it also decided a Haiti mission was too dangerous with success uncertain.

Canada, however, has offered $91 million for Haiti, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised continued support as he addressed the Kingston summit remotely.

Kenya stepped forward but was set back by a domestic court ruling against the deployment.

The plan again picked up steam after Henry visited Nairobi and agreed on a "reciprocal" exchange of forces between the two countries. But with violence soaring, Henry was unable to return to Haiti, landing in Puerto Rico after the Dominican Republic declined to take him.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.