Having A ‘March Madness’ Party? Be Careful What You Call It

The 2014 NCAA Tournament -- also known as March Madness -- is underway this week, and that means college basketball-related events and parties are taking place all over the country. That part you probably know. What you may not know is that the vast majority of those events aren’t allowed to use the term “March Madness.”

Put together, those two words are a protected trademark, one of many licensed by the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the nonprofit trade association that oversees college basketball. The organization, which conducts some 89 championships every year, is known to diligently police its various marks against infringement. On its website, it has even outlined its comprehensive “trademark protection program,” stating that its brands are “carefully controlled and aggressively protected to be consistent with the purposes and objectives of the NCAA, its member institutions and conferences and higher education.”

Sound harsh? Maybe, but trademark experts say such efforts are a necessary part of protecting brands against dilution. “From a non-branding lawyer standpoint, it looks a little heavy-handed, but they do have to control the brand,” said Joanne Ludovici, an intellectual-property attorney and partner at the Washington office of McDermott Will & Emery. “If you own trademarks for a very long time -- famous, well-known, lucrative trademarks -- there’s nothing wrong with letting people know that they can’t just misuse them, even if it’s because they love the NCAA.”

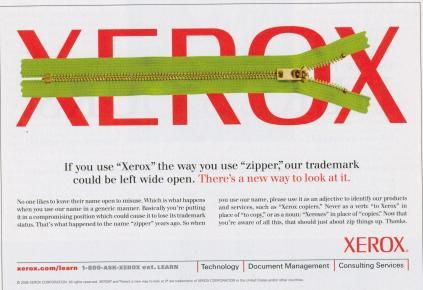

In fact, Ludovici said, she wishes more of her clients would make efforts to be so communicative, letting the public at large know why trademark enforcement is necessary and what is at stake for a brand’s value when it becomes too generic -- a brand can become so diluted that the rights shift to the public domain, making it impossible for the company to license it. As a case in point, she cites the 2010 ad campaign from the Xerox Corp. (NYSE:XRX), which tried to fight back against the “genericide” of its brand name (i.e. people using “Xerox” as a verb meaning “to make copies”). In a series of ads, the company tried to explain to consumers that its brand was at risk of suffering the same fate as words like “zipper” and “aspirin.” The former was originally owned by B.F. Goodrich Company, and the latter is still owned by Bayer. Today both terms are interchangeable with the products they describe. Given the risk of brand dilution, Ludovici said there’s nothing wrong with a trademark owner being proactive. “I always tell my clients, an educational campaign out front of the message and not behind it is a good way to go.”

In the case of the NCAA, it isn’t just “March Madness” that’s at stake. The group owns more than 60 trademarks and corresponding logos, including “March Mayhem,” Midnight Madness,” “Final Four,” “Final 4,” “The Final Four” and of course numerous marks including the acronym “NCAA.” Lawyers for the trade association, and even representatives from its member colleges, are known to send cease-and-desist letters to alleged trademark infringers and even file lawsuits when deemed necessary. A decisive victory in establishing “March Madness” as a protected trademark came in 2005, when the Fifth Circuit sided in favor of the NCAA’s holding company against Netfire Inc. in a cybersquatting lawsuit involving the domain MarchMadness.com. Ludovici said such large-scale infringement is likely much more a concern for the NCAA than, say, a small-town bar owner giving away free nachos at a “March Madness” beer pong event.

“It’s diminishing returns,” said Ludovici. “What are you going to get out of that if you have bigger fish to fry on the Internet, or you’ve got somebody with a billboard in L.A. or somebody who’s operating in 45 of the 50 states? To me that’s a measured balance of enforcement, recognizing that you cannot go after everybody -- and I’m sure they’re not going after everybody.”

This is not to say that local bar owner is off the hook. Ludovici said habitual infringement, no matter how small, is likely to get the NCAA’s attention. She said trademark owners aren’t just looking at the present but also considering the possible consequences of unchecked infringement -- for instance, having their brands associated with an unauthorized event in which something goes horribly wrong. “What if, God forbid, someone gets wasted and gets hit by a car?” she said. “Then it becomes, ‘Who sponsored that beer pong event? Was it Joe Shmoe or was it the NCAA with the deep pockets?’”

If you’re still in doubt, read more about trademark protection on the NCAA website and see a list of its trademark’s here.

Got a news tip? Email me. Follow me on Twitter @christopherzara.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.