Heartbleed Bug Simplified: The Internet’s Illegitimate Child Is Not Through With Us Yet

Tech jargon aside, the underlying mechanics behind the bug are actually quite simple.

Heartbleed, the illegitimate child of the Internet, was spawned on New Year’s Eve, 2011, the product of a late-night miscalculation. His parents are Dr. Robin Seggelmann, a German computer programmer, and Dr. Stephen N. Henson, a veteran cryptographer. Like many unplanned children, he was both unwanted and ignored, a precarious recipe that fostered his later propensity for troublemaking. For more than two years, this silent menace wreaked havoc in the most sensitive corners of the Internet, undetected by those who could have easily put a stop to his mischief. Last week, he got the attention of the Finnish security firm Codenomicon. The company gave him a catchy name -- the Heartbleed bug -- and the rest is Internet infamy.

Since news broke last week that a major security flaw has left half a million trusted websites vulnerable to remote attackers, our overlooked illegitimate New Year’s Eve baby has become something of a household name, thanks in no small part to Codenomicon’s brilliant bit of branding, one that would impress even Sterling Cooper & Partners’ toughest clients. No doubt you’ve seen the ominous yet fetching Heartbleed logo, its dripping streams of blood staring from your computer screen like a brilliant red warning light. While the image has no doubt helped grab headlines, once you start reading the stories about Heartbleed’s havoc, you might find yourself going cross-eyed trying to decipher terms like “cryptographic software” or “private server key.” It’s enough to make you glaze over in defeat, click the next BuzzFeed quiz and forget you’ve ever heard of Heartbleed.

But the underlying mechanics behind the bug are actually quite simple, said Alex Balan, head of product management for the security and antivirus firm BullGuard, who has been trying to convey to laypeople why the Heartbleed bug is so potentially serious. Balan, who spoke to International Business Times from his office in Bucharest, said that despite media characterizations of an evil arch-nemesis bent on tearing down the walls of Internet security, the reality is much more mundane.

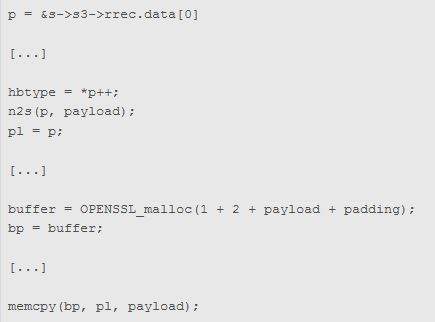

Heartbleed isn’t a virus. It’s not a worm or piece of malicious code. It’s a simple programming mistake, written unintentionally by Seggelmann on that fateful New Year’s Eve. According to an interview he gave to the Sydney Morning Herald, Seggelmann, then a Ph.D. student, was busy working late that night on a research project for the University of Münster, in Germany. The project involved coding bug fixes and new features for a widely used security tool called OpenSSL, a protocol that anyone can update. The open-source OpenSSL project is a mostly volunteer endeavor, save for one paid employee, its lead director, Dr. Henson. At 11:59 p.m. that night, Seggelmann submitted the flawed code to Henson, who reviewed it, and also missed the error. After that, the code was adopted into a development version of the software. And on March 14, 2012, the erroneous code was released with an official OpenSSL update, where it made its way out into the Internet and hundreds of thousands of popular websites.

A troublemaker? Sure, but a misunderstood one at best. If computer code is a language, think of Heartbleed as a typo, one that was missed by multiple editors and copyeditors until it ultimately landed on the front page of a major newspaper. It’s rare, but it happens.

And in this case, the reason that typo is so potentially threatening is because it left a gaping security hole in OpenSSL, which is used to secure communications between servers and computers. Some two thirds of the Internet rely on OpenSSL, including ubiquitous online giants like Facebook, Twitter, Google, Yahoo, Amazon and some financial institutions. The protocol allows the servers of those companies to communicate securely with our computers, laptops and mobile devices. When you sign into Amazon, for example, your device requests information from Amazon’s servers, including sensitive information like your username, password and credit card data. It’s at that exact moment -- when a specific server accesses your private data -- that Heartbleed could potentially pose a serious security threat.

“Think of the server’s memory like your mind,” Balan said. “Whatever is going through your mind right now, what you see in front of you, my words to you, whatever else you’re thinking about -- maybe a hotdog pops in there -- all that information can be scraped off the server, through the Heartbleed bug.”

Fixed… But Not Finished

Fortunately, no sooner was Heartbleed discovered than a patch was created to repair the problem. The patch was deployed on April 7 and, by now, most major Internet companies have implemented it. But that doesn’t mean it will be smooth sailing from here. That’s because, as previously noted, the bug had already been out there for more than two years, and security experts have no way of knowing who, if anyone, has exploited the flaw to steal sensitive data.

And it’s not simply question of taking inventory to see what’s missing. While Heartbleed can be described as a security hole of sorts, as Balan points out, it’s not akin to leaving your front door unlocked for two years. If that were the case, you’d know as soon as you got home if all your furniture was missing. In the case of computer data, which is read remotely and copied from location to location, it’s not so simple. While your data may -- or may not -- have been hacked into over the last two years, you might never know about it.

This is why you should take seriously all those recommendations to change your passwords and user data on potentially compromised websites. “We don’t know your stuff has been compromised until something bad happens to you,” said Bruce Schneier, a security expert and technologist whose blog post calling the Heartbleed bug “catastrophic” went viral last week

“The reason you should change your passwords is because your passwords might have been compromised,” Schneier said. “That’s it.”

Jeremy Gillula, staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said part of the issue with Heartbleed is the sense of helplessness among non-tech-savvy Web dwellers who think they should be doing more to protect themselves. “There’s not a whole lot else that average Internet users can do, because the bug is on the servers,” Gillula said in a phone interview. “It’s not a bug [that] makes your computer vulnerable.” Jen Weedon, a security analyst at Fireeye Inc., concurred. “The average user is dependent on the owner of the website and who administers the Web server” to address the problem, she said.

From Potentially Bad To Theoretically Worse

Gillula, who is based in San Francisco, said the most frightening threat posed by Heartbleed is the possibility that attackers could access a server’s private key. Private server keys verify that your computer isn’t connecting to a phony website (hence the tiny lock icon you see at the top of your browser when you’re on an SSL-enabled website). If fraudsters were to obtain a private key, they could feasibly impersonate a company’s website. In a nightmare scenario, imagine you were to visit a shadow version of one of your favorite trusted websites and start typing in sensitive financial data.

Gillula said an impostor with a private server key would be on virtual Easy Street. “Once you had that key, then you could record the information,” he said. “An attacker wouldn’t have to do anything besides listen to what was being transmitted back and forth between your computer and a server.”

Whether or not a server’s private key was accessed through Heartbleed is still speculative. The good news is, Gillula said, there is a high probability that no one has done this. At the same time, it looks like such a scenario is entirely possible. Last week, the online security company CloudFlare ran a challenge calling on users to see if they could steal a private key on one of its vulnerable servers. It turns out they could, as CloudFlare confirmed in a blog post: “This result reminds us not to underestimate the power of the crowd and emphasizes the danger posed by this vulnerability.”

Gillula said the issue underscores the need for better security features. EFF has long advocated for wider deployment of a system that generates random server keys each time a user connects to a server, a property known as “perfect forward secrecy.” Such a system would have rendered a programming error like Heartbleed far less serious. If a server configured to support perfect forward secrecy was compromised, an attacker would not be able to decrypt past communications. “Even if someone recorded all your data from the last two years, they would have to have gotten the key each time,” Gillula said.

If perfect forward security is adopted by more websites, it could be a silver lining in the dark cloud that is Heartbleed. Our illegitimate child, tantrums and all, may ultimately lead us to a better Internet. Gillula said he is hopeful that people will see this “simple little bug,” and the havoc it can create, and realize that it’s worth the extra cost to make security a little stronger. At the same time, he points to the inevitability of human error, and the relative rarity of bugs of this magnitude, and sees it all as a comforting sign. As we strive for a more perfect Internet, let’s not lose sight of how well it already works. “Given that it’s such a complex system,” Gillula said, “it’s almost miraculous that it works as well as it does.”

Luke Villapaz contributed reporting to this story.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.