Heritage In the Crossfire: How Syria Is Destroying Its Past

DAMASCUS, Syria -- They stand at full attention, their faces stoic, their stony eyes wide. Dozens of them observe the silence, row after row. The tallest in their midst comes up to the knee.

They are the statues of Mari, commissioned some five thousand years ago by the ancient locals near what is now the town of Abu Kamal in eastern Syria.

The short figurines, each thought to have resembled its individual patron, were excavated decades ago from inside long-buried temples. They are believed to have stood facing their deity, serving one main purpose: "So the gods mistake your figurine for you, and think you're always praying," one tour guide at the Damascus National Museum explained.

The Mari civilization is one of many in Syria, which hosts the world's two oldest continuously inhabited cities, Damascus and Aleppo. Scholars say there are surely a myriad of other not-yet discovered treasures.

As a result of what some now describe as perhaps one of the current Syrian regime's few virtues, excavations and heritage preservation was a priority in the country since the early '70s, when authorities passed tough laws to protect heritage sites and the Syrian Dept. of Antiquities developed an international reputation for being enlightened and visionary.

"They decentralized museums, building numerous small and local ones to educate locals about their own history, and to keep local finds near original sites," said Helen Sader, Chair of the History and Archeology Department at the American University of Beirut.

Encouraging international excavation teams and tourists to come to Syria paid off. Up until just before the conflict began 17 months ago, Syrian cities were brimming with exquisitely restored sites, including some that were transformed into boutique hotels that ended up featured in Condé Nast Traveler and other glossy Western magazines.

The New York Times even named Damascus, Syria's capital, among the world's top ten places to visit in 2010.

Now, much of this heritage is in great danger. Looting has become endemic in recent months. Shelling, aerial bombardment and gunfire have eaten away at spectacular landmarks and UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

While rebels bear part of the blame, most of the irreparable damage to Syria's sites seems to have come from government forces themselves.

A preliminary investigative account sponsored by the World Heritage Fund, called Damage to the Soul, by Emma Cunliffe, a scholar at Durham University in the United Kingdom, documents some of the problem.

Cunliffe says that "tanks and heavy weapons have been positioned, and barracks built," near some of the country's pre-Roman ruins. The account mentions one incident in which government forces bulldozed an ancient wall to make an opening, presumably in pursuit of rebels. It also records numerous examples of damage to historic landmarks due to shelling.

The most recent such incident happened last week, when government forces started pounding the town of Krak des Chevaliers, located near its namesake UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Krak des Chevaliers is an imposing Crusader castle, known as one of the best preserved castles in the world.

While it is not yet clear how much damage, if any, the shelling has caused, the site was damaged earlier this year. According to one activist who goes by the nom de guerre Prinz of Homs, blame lies mainly with government forces. He described what happened the last time government troops came looking for rebels near the site.

"Government forces arrived in hot pursuit, and they clashed with the rebels in the village," he said. "Some rebels and villagers escaped up the hill to the castle. Everyone thinks it's safe up there. It's made of stone and it's higher ground. But government troops shelled the castle anyway."

Palmyra is another UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in central Syria. Described as one of the most important ancient cities, it fused Greco-Roman styles and architecture with Persian influence.

Beginning a few months ago, Syrian government tanks travel regularly along the periphery of the site, close to triumphal arches and ancient tombs. Local activists say the area is cordoned off by the Syrian military, but recent damage was visible.

"We're very worried about the Temple of Bel," an activist who goes by the nom de guerre of Majd the Palmyrian said. Bel was a major Semitic god.

"The soldiers drive their tanks on roads that used to be closed off to cars because the slightest vibration can damage the columns," he said.

He added that locals suspect that soldiers are looting the site. He said the military has set up posts around the ancient ruins, preventing anyone from going near them. New tunnels and holes have been emerging all over the area.

"One tomb has completely collapsed because of the tunnels underneath it," said Majd, who provided a YouTube video purportedly showing Syrian troops posing against the backdrop of the city's ancient ruins. Another video shows suspected regime thugs stealing artifacts, shown packed and handled unprofessionally in the back of a pickup truck. There are also photos of Syrian soldiers playing with artifacts.

The International Business Times is unable to verify the authenticity of any of the photos.

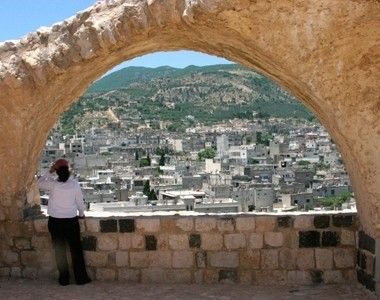

Earlier this month, government shelling caused damage to another of Syria's spectacular monuments, the Aleppo Citadel. Again, it was much the same story. Rebels and locals trying to escape the gunfire fled into the Citadel, hoping they had reached safer ground. Government troops opened fire with artillery, causing visible damage to the Citadel's entrance.

The Citadel sits atop layers of settlements that date back at least 5,000 years. For many Aleppoans, the Citadel is much more than a monument. It is part of the city's psyche.

"When I first heard about the damage, I wished it were my home that had taken the shell instead of the Citadel," one Aleppoan said.

As for Homs, the loss of heritage there is perhaps among the worst so far in Syria, starting with the city's ancient souk, or marketplace. It had been a fully functioning bazaar for centuries, commonly called "The Covered Souk." Now it has lost its ceiling.

The Damage to the Soul report features a dizzying list of reports of damage that occurred at more than two dozen other sites in Homs, including damage to centuries-old mosques and churches.

One of the churches is the Umm el-Zinnar Cathedral, a 2,000-year-old site. Beneath its rubble now lies its most precious keepsake: a belt made of fibers. It is said to have belonged to the Virgin Mary.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.