High Cost Of Healthcare: Medical Apps Promise Better Health, Lower Costs And More Time, But Can They Change US Health Industry?

In 2011, Ammar Siddiqui, a senior medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, was volunteering in the East Harlem Health Outreach Partnership, a student-run clinic for uninsured patients. As the student overseeing referrals, he was overwhelmed by hundreds of daily emails from students asking questions -- from whom to call to refer a patient to a specialist to how to order a medical test, he recalled.

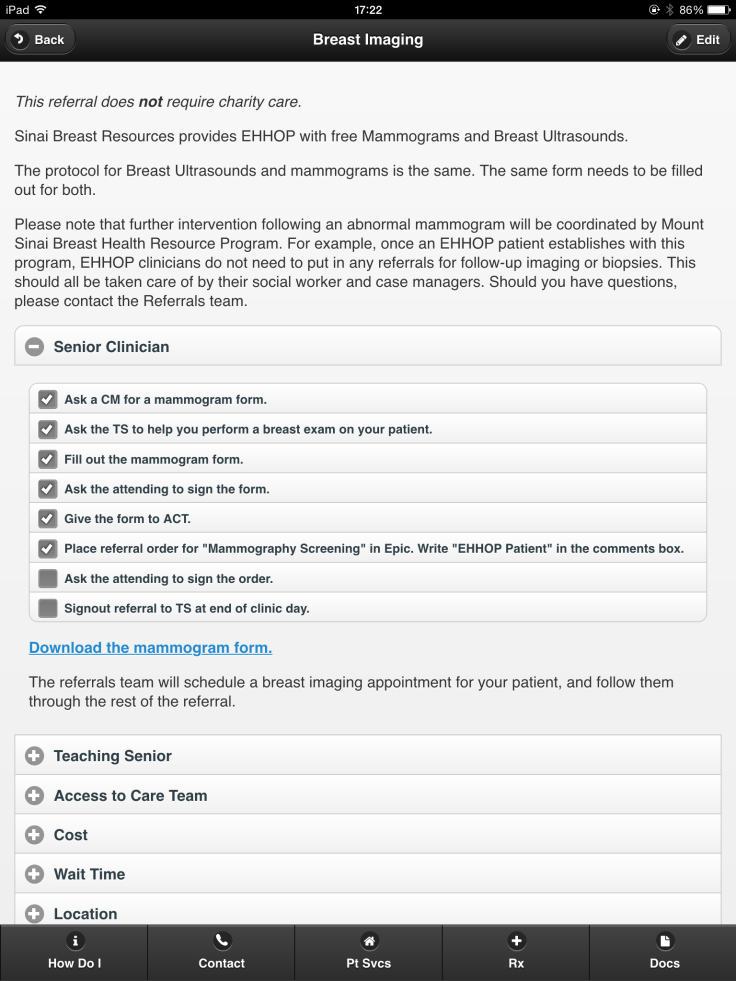

To stem the tide of emails, Siddiqui built a website where students could find answers to their questions independently. That site grew into an app, developed by Siddiqui and several other medical students. Launched in June 2012, it laid out the clinic's often labyrinthine protocols, generally invisible to patients, in step-by-step fashion. With it, figuring out how to scan documents or order medical tests could be done with the tap of a finger. Soon, Siddiqui and his colleagues had built a generic version of their app, which they called CareTeam, and began delivering customized versions to a growing number of clinics at Mount Sinai Hospital as part of the East Harlem Software Company, which they incorporated this year.

With CareTeam, the students are throwing their lot into the fray with hundreds of thousands of other healthcare-related apps, joining an expanding yet increasingly fragmented pool of medical e-resources designed to make it easier for doctors to navigate the nation's complicated healthcare landscape. Revenue from mobile health apps is expected to reach $26.5 billion by 2017, up from just $2.4 billion in 2013. But while doctors and patients alike have become increasingly tech savvy, many healthcare professionals said the industry has struggled to come up with a digital solution that can address the inefficiencies and bureaucratic woes that plague healthcare in the U.S.

“Medical students at every institution are developing apps,” said Jonathan Weiner, a professor of health policy and management and health informatics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. But that doesn't mean the healthcare industry is better off, because the apps aren't necessarily complementary with each other, or other electronic systems. “They don’t always fit into this bigger digital milieu,” Weiner said.

Doctors On Smartphones

Just as people turn to devices like Fitbit and Apple Watch to track exercise, nutrition, sleep and a host of other health metrics, certain apps have become go-to resources for doctors and nurses as they diagnose patients and prescribe medications. In recent years, both the supply and demand for these resources have experienced rapid growth.

In 2007, 39 percent of physicians used smartphones for work. By 2015, 84 percent of doctors did, while more than half of doctors used tablets, a survey in March showed. On the software side, in the first quarter of 2014, more than 100,000 mobile health apps were offered for Apple iOS and Google Android devices combined, a 2014 report by research2guidance, a market research company, found. That number had more than doubled in the previous two-and-a-half years.

For the most part, these apps are not geared toward doctors and their clinical work. In fact, only 14 percent of app developers targeted physicians, research2guidance’s report indicated. The medical reference apps Epocrates and Medscape, for instance, are both widely used by doctors and nurses. Medical professionals generally rely on technology to manage their time, access health records and look up symptoms and treatments.

Doctors tend to think that both they and their patients benefit from access to healthcare apps, and studies indicate that having a mobile device allows doctors to be more efficient and take better care of their patients. Doctors, hospitals and clinics are under constant pressure to provide better care at a lower cost, particularly as the healthcare system continues to shift from fee-for-service payment models to those based on the quality of care. If an app saves time or improves the quality of care even incrementally, over time those effects can add up to tangible benefits.

Tech-savvy medical students and the younger generation of doctors are particularly embracing, if not devising their own, apps. Of medical and other healthcare students, 85 percent report using a mobile device at least once a day for clinical purposes, such as looking up drugs or talking with other doctors and students about patients, noted a 2014 paper in the journal Pharmacy and Therapeutics.

“It’s part of a huge trend,” Weiner, the Johns Hopkins professor, said.

But as more apps are created and customized for specific needs, they don’t always fit smoothly into a broader picture or hospitalwide system. Because hospitals and clinics use different systems for electronic health records, for instance, an app that doctors might use to share records within one system does not always work in another.

“A thousand apps does not an efficient healthcare system make,” Weiner said.

Some health experts said that while the apps contributed services here and there, they were not radically changing the way doctors practice medicine. “Most of the apps that we’ve covered are sort of additive,” Jonah Comstock, managing editor of MobiHealthNews, a news and research site that focuses on the global mobile health community, said. “They’re a nice kind of bonus,” he described.

Akhilesh Pathipati, a third-year medical student at Stanford University in California, said that, in teaching hospitals, experienced doctors expect to field questions from students and less experienced doctors. Still, he admitted that technology could have a positive impact in those scenarios.

“There is certainly time that can be saved if you’re able to answer these questions electronically,” he said.

A Piece Of Work

Whether any clinical app succeeds depends on how well it can be integrated into a larger system. For CareTeam, that remains to be seen largely because the app is not a one-size-fits-all solution. It is more like a skeleton that has to be packed with content specific to a hospital or clinic.

Nevertheless, CareTeam's developers see their template as broadly useful. It collects and organizes institutional information cleanly, making it readily accessible to doctors and other medical providers. And even though the process of customizing the app is time- and work-intensive, requiring employees of a hospital or clinic to contribute insider knowledge, its users say that labor pays off.

“Usually there’s one person who’s emailing everybody this stuff all day,” Ted Pak, one of the app’s developers who is earning a medical degree and a Ph.D. at Mount Sinai, said. Using an app instead to find answers could save everyone time, he said.

Before the Internal Medicine Associates, Mount Sinai’s primary care clinic, launched its version of the CareTeam app in mid-June, Dr. Aparna Sarin, an assistant professor, used to print information -- detailing where to send a patient with diabetes, how to call security, or how to order a colonoscopy, among other things -- on four separate pieces of paper and walk to four different locations, posting a copy at each. If a critical phone number changed, that meant four new printouts and four more walks were required to swap them out.

Now, Sarin is an enthusiastic champion of the CareTeam app. “It eliminates so many tiny little steps that add up over the course of a day,” she said. It was Sarin who compiled all the information that she once physically tacked to walls into a neat, 13-page document that she gave to the East Harlem Software Company so they could build the app.

At Mount Sinai, six clinics or hospital departments are currently using versions of CareTeam, and several other departments want their own. Sometimes Pak and Siddiqui overhear people talking about it around campus, and they like to joke that they feel like they’ve “made it.”

Yet even as the East Harlem Software Company's student leaders dream big, they are well aware of the uncertainties that lie ahead. “Now, we’re testing this idea of, ‘Is this widely applicable?’” Kevin Hu, the company's president and a fourth-year medical and public health student at Mount Sinai, said. “Will a lot of people really find a lot of utility in it? I think that’s the next step.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.