High Hopes As North Macedonia Eyes Cannabis Potential

After receiving a suspended sentence for possession of cannabis last year, Filip Dostovski walked out of the Skopje courthouse and lit a joint outside as cameras rolled.

It was an act of "revolt against their sentence and against their policy", said the 41-year-old cancer survivor, who is pushing for the free use of marijuana in North Macedonia.

The Balkan state is eyeing a chance to become a cannabis pioneer in Europe, as the government considers legalising marijuana in what would be a first on the continent.

But many worry about a lack of follow-through, a problem that has dogged the government's drug policy for the last five years.

Home to little over two million people, North Macedonia legalised the cultivation and sale of marijuana-derived medical products in 2016, hoping to get the edge in a fast-growing European market.

However, the law is unclear and has left the sector in limbo, with most businesses unable to sell on the international market.

At the same time, private individuals seeking to grow and consume marijuana risk criminal prosecution.

Medical prescriptions are only allowed for a narrow list of illnesses.

"The good thing is we have a law for cannabis production, but the bad thing is the law is awful," said Filip Sekuloski, who leads a local NGO promoting more liberal cannabis policies.

Prime Minister Zoran Zaev has recently promised to loosen regulations on the medical use of cannabis and hold a public debate on decriminalisation and legalisation for recreational users.

He has referred to Amsterdam's coffee shops as a model for the capital Skopje and other tourist towns.

While the Dutch city is considering barring foreigners from its cannabis cafes, citing their nuisance, North Macedonia, one of Europe's poorest countries, is eager to welcome additional visitors.

"I see it as a source of economic potential," Zaev said.

Health Minister Venko Filipce also supports the move.

"It is a field that has a huge future, a field that really offers development, that means serious investments," he told AFP.

Even if the government backs legalisation, it is likely to hit resistance from political opponents.

Falkron Bexheti, from an opposition party representing ethnic Albanians, has argued the country needs a "functional legal system" before it can make such a change.

"We are not ready as society for something like that," he has said.

Other foes point out that the prime minister's relatives are involved in the sector, which Zaev has previously dismissed as irrelevant.

In Dostovski's view, the main challenge will not be public opinion but rather a game of "political points and political bargaining" between rival camps.

He also believes authorities fear upsetting gangs who run the black market.

The government says the priority is to fix the existing law to allow medical producers to export the plant's dry flower -- the product that makes up most of the European market.

Currently, companies can only sell extracts such as oils that are expensive and complicated to make.

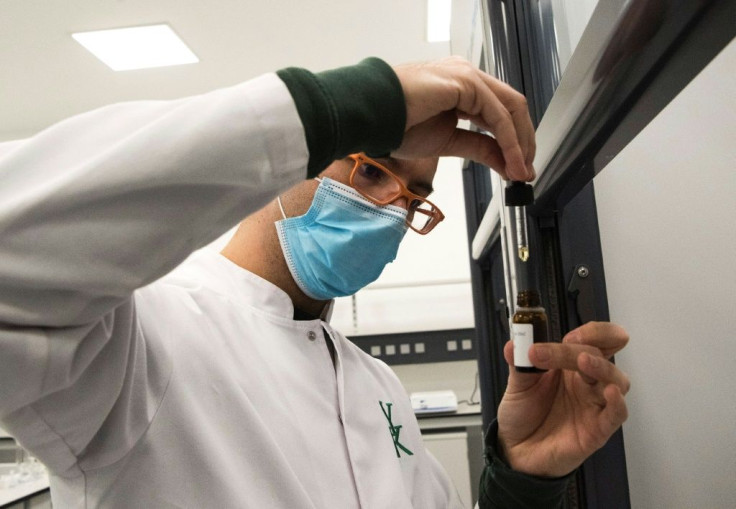

Of some 60 local firms that have secured licences to grow cannabis, NYSK Holdings is one of the few with enough capital to produce extracts that meet European pharmaceutical standards.

But it is also waiting for the government to allow the export of the flower itself.

Late last year, the firm, a partner of Poland-based PharmaCann, opened a gleaming 17,800 square-metre (191,600 square-foot) facility near Skopje's airport.

Inside the compound, surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, marijuana plants are raised from seed under purple heat lamps before being transferred to a humid grow house, where horticulturists in protective gear tend to them.

Chief executive Zlatko Keskovski worries the multi-million-dollar investment will be a waste if the government keeps dragging its feet.

A flurry of interest from international companies who visited in 2018 may go to other up-and-coming rivals in Malta and Greece, he warns.

"The worldwide market is very huge, but at the same time we have huge competition."

When it comes to recreational use, legalisation advocates stress the potential economic gain in a country where monthly salaries average 460 euros ($548).

It would mean "erasing one black market and offering a legal turnover of money, new employment, new tax income," said Sekuloski.

Others note cannabis is already widely used and that regulation would simply make it safer, cutting off the influence of traffickers from neighbouring Albania.

"It does not mean that Macedonia will be flooded with marijuana and everybody will smoke on the streets and the kids would become drug addicts," said Ognen Uzunovski, a 47-year-old cafe owner in Skopje who is part of the Operation Liberation movement in favour of legalisation.

He cited countries like Uruguay, Canada and a growing number of US states where the process has gone relatively smoothly.

But in Europe, decriminalisation is the preferred approach, where users are not prosecuted for possessing small amounts but still buy off the black market.

In North Macedonia, punishments vary at the discretion of law enforcement.

"I know people with five grams that went to jail, and people with 50 grams who were just fined," said Dostovski.

The activist ran into his own legal trouble in 2016 when police found several hundred grams of cannabis in his Skopje apartment.

He was using the plants to make an oil he believes has curative properties for serious illnesses, though medical studies are lacking.

Dostovski says the oil reversed a scary bout of swelling in his lymph nodes years after he had been treated for Hodgkin's lymphoma, and he has been helping others make the oil ever since.

He believes legalisation is inevitable but not for about five years yet.

In the meantime, he stands behind the slogan of his NGO Green Alternative: "Good people disobey bad laws".

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.