Homeless But Not Forgotten In UK's Covid Jab Drive

Mac is only 25, normally too young to be eligible for the British government's Covid inoculation campaign at this stage.

But he's still terrified of catching the virus.

"I don't want to die from Covid!" he says.

Mac is homeless, and therefore qualifies for priority vaccination to ensure the most vulnerable are also protected. They include other younger people with acute medical conditions or learning difficulties.

Homeless since the age of 18, Mac has been offered a first jab in April at a shelter in the southern city of Winchester, the ancient capital of England known for its cathedral and an elite private school.

For all its history and gentility, Winchester is no stranger to the problem of homelessness, which has grown across Britain following years of budget cuts following the 2008 global financial crisis.

"If I wasn't sleeping in the night shelter I wouldn't have been offered it at all," Mac told AFP, his long blond curls peeking out from under a hoodie.

"There are many people I know living in tents, in the countryside. Around here is very rural, you would never find them."

Mac and others at the shelter were found thanks to the community outreach work of local doctor Alex Fitzgerald-Barron.

"The homeless are high health-risk patients because they are in a multitude of diagnostic categories," he said, listing mental health problems and frequent pneumonia, along with oral and skin infections.

"They are at high risk of hepatitis C because of injecting drugs," Fitzgerald-Barron added. "They are much more likely to end up in hospital if they catch Covid -- and to die from it."

Britain last week marked the anniversary of its first coronavirus lockdown, paying tribute to the more than 126,000 people who have died -- one of the world's worst tolls.

A year ago, the government ordered everyone to stay at home. For those without a home, it directed local councils to throw open emergency shelters and paid for rooms in hostels.

But complaints were rife that social distancing was impossible in cramped shelters, hastening the spread of Covid-19.

And the homelessness charity Shelter has warned that the "economic fallout of 2020 may turbo-charge this crisis" as the latest lockdown is wound down.

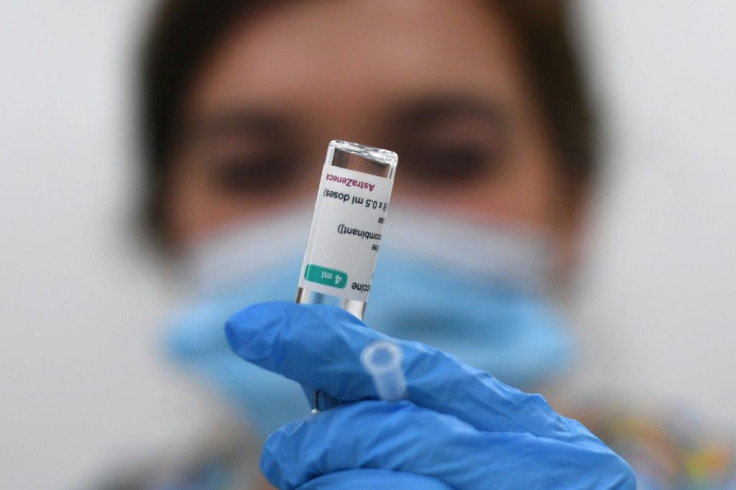

The easing of restrictions is possible thanks to the vaccination campaign, which is currently targeting people aged over 50 in the general population.

More than 30 million people have now received at least a first dose, and the government intends to cover every adult with at least one shot by the end of July.

"It's so important that nobody gets left behind in this national effort," Health Secretary Matt Hancock said, when he announced in mid-March that the campaign would start prioritising the homeless.

"We know there are heightened risks for those who sleep rough."

But Fitzgerald-Barron had already begun to target the homeless, using his medical judgement to classify them as "extremely vulnerable", one of the first groups inoculated alongside the very old.

While other medics work out of mobile clinics, the Winchester doctor uses a small fridge that he plugs into his car, loaded with the day's doses.

When Fitzgerald-Barron arrives at a shelter, he plugs the fridge into the mains electricity. He started offering jabs in February, making face-to-face contact with 114 homeless people, 74 of whom agreed to be vaccinated.

He considers that number "a good result", made possible only by a "personal relationship of trust".

"I had to be in front of them to explain what it is," Fitzgerald-Barron says.

More than other groups, according to people involved, the homeless are often scarred by past encounters with officialdom and more prey to anti-vaxx hoaxes.

"I think this is all a big conspiracy to control the population," said one woman, Leighan, 35, who refused the invitation from Fitzgerald-Barron.

For those like Mac who did take up the doctor's offer, the worry is what happens after the lockdown is lifted and the pandemic is considered over.

"The government hasn't yet set out their (homelessness) strategy as the pandemic eases," said Jasmine Basran, policy and public affairs manager at the charity Crisis.

Despite the government's pledges last year of financial support, when the first lockdown finished in June, "some people were turned away from support" by local councils, she said.

Fitzgerald-Barron has a more immediate concern. In April, it will be time to administer second doses at shelters, 12 weeks after the first round.

"The risk is some of the people that we vaccinated in February are not there anymore," he warned.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.