Homeward Bound? Deadline Looms For North Korea's Overseas Workers

The waitress at the North Korean restaurant in Beijing has no concerns about a deadline this weekend for Pyongyang's overseas workers to be returned. "I'll go home for the holidays," she says. "But I'll come back."

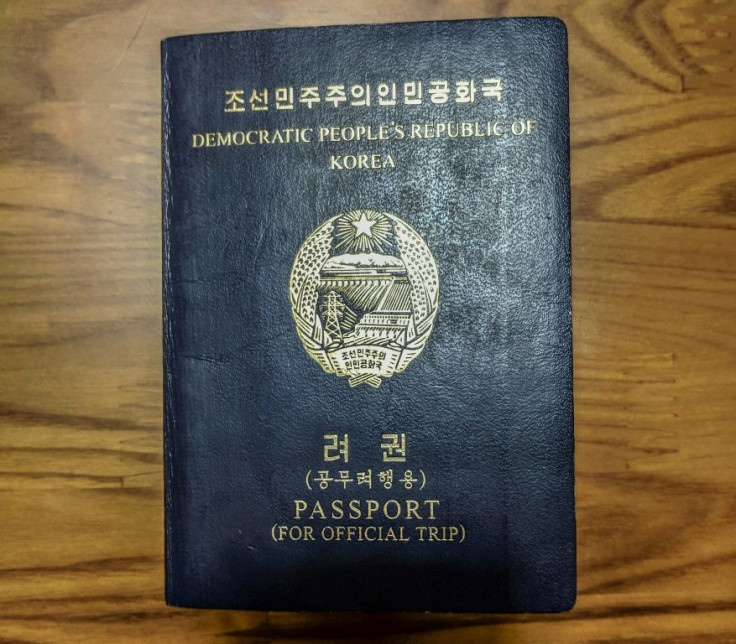

Nuclear-armed North Korea has long made a fortune from the army of citizens it sends abroad to work, mostly in neighbouring China and Russia but also as far afield as Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

Two years ago, the UN Security Council ordered the countries where they work to send them back as part of the efforts to press Pyongyang over its nuclear and ballistic missile programmes, with complete compliance required by this Sunday.

But analysts say Beijing and Moscow are circumventing the measure by issuing North Korean workers with alternative visas to ensure a continued supply of cheap labour.

Longstanding allies of Pyongyang, the two called this week for several sanctions -- including the ban -- to be eased, with nuclear negotiations between the United States and North Korea at a deadlock.

China was estimated to have 50,000 North Korean workers when the resolution was passed, and witnesses and reports say North Koreans continue to enter the country to work in border-region factories.

At Unban, a North Korean restaurant near Pyongyang's sprawling embassy in Beijing, a waitress told AFP she had worked there for four years and expected to continue.

"No one has told us that the restaurant will close," she added. "We had two new colleagues who came last month."

Foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said last week that China "earnestly" implements all UN resolutions, but declined to say how many North Koreans were working in the country.

Moscow's ambassador to Pyongyang Alexander Matsegora said in September that the number working in Russia had already been cut from more than 30,000 to less than 10,000.

"After December 22, there will not be a single North Korean in Russia with a work visa," he told the RIA Novosti news agency.

But the key sanctions text -- paragraph 8 of resolution 2397 -- does not specify visa types, referring more broadly to "all DPRK nationals earning income".

And Kang Dong-wan, a professor at South Korea's Donga University, told AFP: "Since Russia can't issue new work visas due to sanctions, the North Korean workers are going there on tourist visas."

Figures from Russia's interior ministry show that in the January-September period, Moscow issued six times as many tourist visas to North Koreans as it did in the whole of 2018, and three times as many student visas.

Across the two categories, Russia granted nearly 20,000 visas in nine months of 2019. For all of last year, it was below 5,000.

The workers deadline comes with tensions rising again: it will soon be followed by a year-end limit Pyongyang has set Washington to offer it fresh concessions.

According to estimates by the US mission to the UN, the overseas workers -- many employed in construction, factories and forestry -- are worth more than $500 million a year to Pyongyang.

Former North Korean workers say they received only a fraction of the sums charged for their services.

Ro Hui-chang, a defector who supervised workers in the Middle East and Russia for nearly a decade before fleeing to South Korea, said firms paid $1,500 per month per person on average -- 90 percent of which went straight to the Pyongyang government.

"It was free money that came in without fail when they sent their people overseas," Ro told AFP.

Living and working conditions were dismal, he added, with the shortest shifts lasting around 12 hours.

"There was a fixed hour for waking up, but no set time for the day's end," he said.

Even so, overseas work has long been sought-after in the impoverished North, where incomes are a fraction of those in the democratic and capitalist South.

It sometimes offers the chance to make money in side employment or small businesses, and on average they save $1,000-$2,000 a year, according to Andrei Lankov of Kookmin University in Seoul -- far more than they could earn at home.

Workers needed a good background with no family history of political crimes -- many were members of the ruling Workers' Party -- and were "always paying bribes to be selected", he told AFP.

Conditions were hard "but usually less harsh than inside North Korea", he added, and most returned with enough savings for a small business, "planting seeds for new independent non-state economy".

As such, he said, the ban was misplaced, as people who worked abroad gained "a very different picture of the world" and became a force for change in North Korea.

"These sanctions on labour export is counter-effective, counter-productive, immoral," he said. "They are hitting elite to some extent, but they are hitting the common people much more."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.