This Is How Earthquakes Cause Towering Tsunamis

We typically associate ocean waves with wind and the moon, but those natural forces are not the only things that can cause water to build up and crash down — the rumbling ground during an earthquake can create the biggest waves of all.

On an average day, waves come from energy that is acting on the sea. According to the National Ocean Service, part of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the wind blowing across the ocean surface creates friction that builds into a wave’s crest. And the moon acts on a large body of water because of gravity: There is a constant gravitational pull between the Earth and our natural satellite, which contributes to the tides; that’s why we call them tidal waves. The sun’s gravity also has this effect on us.

It is of course no secret that a natural disaster can greatly influence the ocean as well — hurricanes do it all the time. The whipping winds and pressure changes that come with a tropical storm create storm surges, the water that is blown to the shore and submerges coastal areas.

But earthquakes don’t huff and puff; they work differently to send water crashing onto land.

Just like water ripples when a rock is dropped into a body of water or even a puddle and displaces the water in the spot where it landed, the displacement of ocean water during an earthquake creates ripples that grow larger and larger as they make their way to the shore. When its large amounts of water that are being displaced during that shaking, tsunamis form.

In a subduction zone, the location where two tectonic plates meet and one is forced underneath the other, large sections of the Earth’s crust might get consumed. During an earthquake caused by this movement, UNESCO’s International Tsunami Information Center says that amount of crust eaten up could be as little as a few miles of ocean floor to hundreds of miles, and it creates vertical displacement in which the land moves upward or downward. That change in elevation is what moves the water around and allows tsunami waves to form.

Tsunamis can grow dozens or hundreds of feet into the air and move hundreds of miles per hour. When they strike land, they can kill people and destroy buildings, setting off a chain reaction of hazardous conditions.

Why it matters

This could be important for people living in the Pacific Northwest, where scientists say an enormous earthquake — what they are referring to as the “big one” — and subsequent tsunami might be coming.

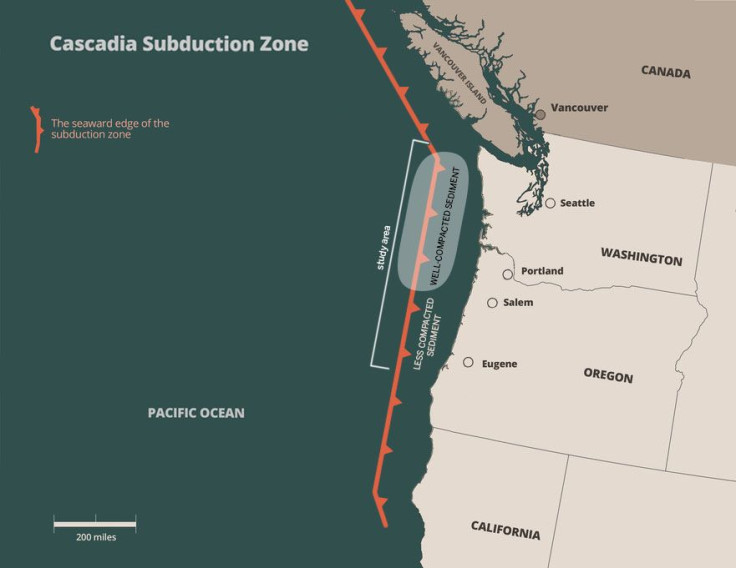

Researchers are saying that large areas of compacted sediments in a subduction zone could be responsible for big offshore earthquakes and the tsunamis that occur afterward. And according to the University of Texas at Austin, Washington state and northern Oregon could fall victim to these natural disasters soon, because an offshore subduction zone called Cascadia is under stress from compacted sediments.

Under the sea just off those states’ coasts, “sediments were tightly packed together without much water in the pore space between the sediment grains — an arrangement that can make the plates more prone to sticking to each other and building up high stress that can be released as a large earthquake,” the university explained. “In turn, the compacted sediments could boost the ability of large earthquakes to trigger large tsunamis because the sediments are able to stick and move together during earthquakes. This can boost their ability to move massive amounts of overlying seawater.”

Those sediments build up as one tectonic plate is driven below another. As the lower one is being squeezed under, it scrapes off some sediment, creating a buildup of material that — if compact enough — increases the amount of stress at these zones, which are capable of creating the biggest earthquakes.

“The Cascadia Subduction Zone generates a large earthquake roughly every 200 to 530 years,” the university said. “And with the last large earthquake occurring in 1700, scientists are expecting a large quake to occur in the future, although it’s impossible to pinpoint the timing exactly.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.