How Humans Evolved: Prehistoric Fish Fossil Holds Clues About Our Skulls

A 400-million-year-old fossil of a human ancestor has clues for scientists about how our species evolved, but it’s not the kind of fossil you would imagine — it’s the jawbone of a fish.

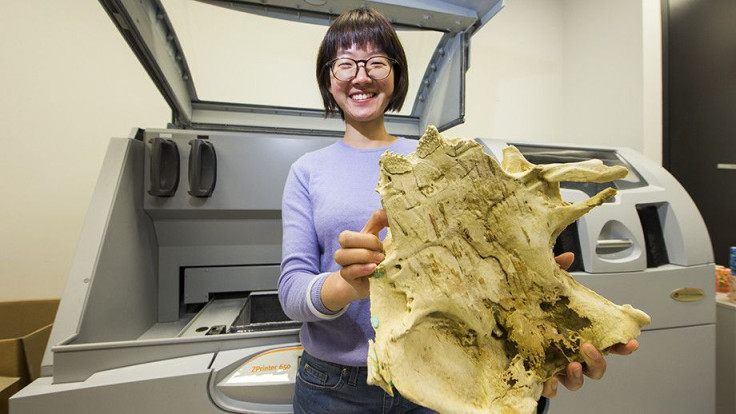

According to a study in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers investigated the inner components of a skull from a fish belonging to a long-extinct class in the animal kingdom, including tracing the paths of blood vessels to see how the brain got its oxygen. The group was able to dig deep into the bone with the help of a 3D printer: After taking a CT scan of the fossil that captured information about all of its layers, inside and out, the team printed out a 3D model that was six times the size of the original.

“Reassembling and manipulating 3D printouts demonstrates the limits of jaw kinetics,” the study says.

That view of the bone shows a link between different evolutionary steps of prehistoric fish, giving a window into how that area of the skeleton evolved in vertebrates, including how the jaw attached to the back part of the skull that housed the brain.

The fossil was found in limestone at Lake Burrinjuck in southeastern Australia, close to the capital Canberra, and is from one of an extinct group of armored fish known as placoderms.

“The fossil reveals, in intricate detail, the jaw structure of this ancient fish, which is part of the evolutionary lineage that ultimately led to humans,” researcher Yuzhi Hu said in a statement from Australian National University. “The jaw joint in this ancient fish is still in the human skull, but is now part of the middle ear.”

Scientists have only recently drawn a connection between placoderms and humans, after finding a new type of placoderms in China with upper jaws more similar to those found in humans today.

According to study co-author Jing Lu, the Australian specimen, which was well preserved, helps to understand the Chinese ones: “Thanks to the international collaboration, we are making great progress to work out the sequence of key evolutionary innovations at the origin of the jawed vertebrates.”

The fossilized skull was indeed so well-preserved that, using the high-resolution CT scan and 3D-printed model, the researchers were able to see the grooves in the bone where blood vessels once ran, carrying blood to both the jaw and to the brain.

“The carotid arteries in humans and other mammals bring blood through the neck to supply the head with oxygen,” researcher Gavin Young said in the statement. “The intersection of grooves on the floor of the braincase in the Burrinjuck fossil shows the blood was flowing in the opposite direction in the equivalent of the external carotid artery, which supplies blood to the jaw and face in humans. This was the main oxygenated blood supply to the internal carotid artery, which forms a distinct groove leading to an opening where it entered the brain cavity.”

CT scans are being used more and more on fossils because they allow scientists to peer inside specimens without damaging the delicate objects. Just recently a group of researchers scanned the bones of a dinosaur that had been discovered and dug up 200 years ago, well before the technology was available. Inside the skull they found teeth hidden in the jawbone.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.