How To Stop The Next Ebola Epidemic: Invest In Basic Public Health, Not Just Vaccines, Experts Say

In the summer of 2014, several months after Ebola had broken out in Liberia, a group of medical workers who had been working on the front lines in the West African country were infected with the deadly virus. An ambulance took them to a designated Ebola Treatment Unit built to accommodate 30 people. When they arrived, at least 100 patients milled about in the rain, waiting to enter the unit. And so the workers waited in the ambulance -- for eight hours.

“They didn’t have space to accommodate them,” recalled Rose Macauley, who at the time was overseeing the medical workers as the chief of party for a program called Rebuilding Basic Health Services. Now the country representative in Liberia for John Snow Inc., a U.S. public health consulting firm, she recalled that although the workers eventually entered the treatment unit, in the end, not all of them survived.

A year and a half later, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa that killed more than 11,300 has been declared over, and world leaders are reflecting on lessons from the epidemic in the hopes that they can prevent, or at least be better prepared for, the next one. Much of the focus has been on treatment and vaccines; Drugmaker Merck and Gavi, the Global Vaccine Alliance, announced Wednesday at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, a $5 million deal for an experimental Ebola vaccine. But public health experts say that these efforts, while important, are overshadowing less glamorous but equally vital work, like creating basic healthcare infrastructure that could go much further in staving off future outbreaks, not just of Ebola but of other diseases as well. Yet these crucial, if mundane, tasks have long failed to attract the same attention and financial support from the organizations and donors that are so influential in global health today.

“What people tend to talk about are more vaccines and more therapeutics,” said Chris Woods, a professor of global health at the Duke Global Health Institute in Durham, North Carolina. Nevertheless, “the best way to control and fight Ebola is through routine public health measures,” he said. “It’s not sexy or exciting, but that’s where the impetus and the resources really need to go.”

The Ebola outbreak, which in addition to Liberia also ravaged Sierra Leone and Guinea, began in March 2014. All three countries recently emerged from years if not decades of conflict or full-fledged civil war, that left overall infrastructure, not just healthcare facilities, in shambles.

“Once the disease started in the capital [Monrovia], it spread very quickly,” Macauley, who worked with the Liberian Ministry of Health throughout the epidemic, said. “It got out of hand,” she said, because the system was not designed to handle so many people, struck by a disease that was new to West Africa.

If a vaccine against Ebola existed -- the deal announced Wednesday between Merck and Gavi was for an experimental drug -- of course it would help save lives, experts said. But other, more basic steps, might ultimately save more.

Back to Basics

A slew of seemingly mundane public health improvements could play a major role in preventing future outbreaks, experts said, pointing to better access to the most basic supplies, better diagnostics, better training for healthcare workers, better education and awareness.

When a person is infected with Ebola, one of the first signs is often a fever. Diarrhea or vomiting are other symptoms, but those problems could also suggest any number of illnesses, from mosquito-borne Dengue fever to the numerous possible effects of the bacteria salmonella.

Without fast, accurate diagnostic tests that determine the exact cause, “there’s a large gap between what they’re potentially treating and what may be actually causing the disease,” Woods, the Duke professor, said.

That means that patients with these symptoms, regardless of whether they’re actually infected with Ebola, enter Ebola treatment units, where they mingle with those who do have the virus and are almost certain to have it when they come out.

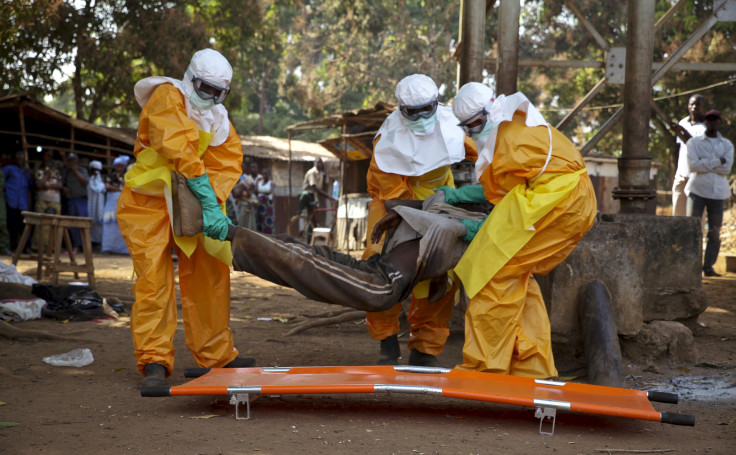

In Liberia, healthcare workers did not even know what Ebola was, Macauley said. They didn’t know basic infection control practices to stop the virus, which is highly contagious and is transmitted human-to-human via bodily fluids. For months after the outbreak began, clinics lacked such essentials as medical gowns and gloves, or chlorine for disinfecting.

Some said that the lack of infrastructure extended even beyond healthcare.

Liberia’s roads were also a problem, Macauley said. Even when new Ebola patients had been diagnosed, a road didn’t always exist to get to them. “It was a major challenge to reach people in the rural part of the country,” she said.

The problem is not so much with identifying what needs to be done, experts said, but with getting the support and the financing to do so.

Targeting Specific Diseases

The first decade of the 21st century saw funding to a select type of global health organizations, like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and the GAVI Alliance, skyrocket. Pledges to the Global Fund soared from $852 million in 2001 to $3.6 billion in 2012. Over that same decade, global health funding for malaria grew 778 percent, tuberculosis 613 percent and HIV and AIDS 603 percent, data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington show. By comparison, investments in “health sector support” increased just 263 percent, and in non-communicable diseases, like cancer, 184 percent.

Sources & channels of #globalhealth funding by health area,@IHME_UW report http://t.co/R600wSMXfM #HIV #malaria #NCDs pic.twitter.com/KtUUXLLKcu

— Ani Shakarishvili,MD (@AniShakari) June 22, 2015

The reason these kinds of targeted initiatives were so popular is precisely because they focused on just one problem or disease at a time, Devi Sridhar, a professor in Global public Health at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and the author of a forthcoming book on the global health initiatives, has pointed out.

When big players on the global health scene, like the U.S. government or the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, donate money, “they like to finance things that are measurable in a short time scale, that show results,” Sridhar said in an interview.

It’s easy to report how many people received a vaccine or a medication, she said, whereas it’s much harder to quantify the effectiveness and impact of building a health clinic. In the current global health system, donors want accountability and hard numbers showing that their money has produced tangible results -- and the more easily quantifiable vaccines and medicines generally target one or a few diseases, not public health at large.

Many find this trend alarming. A recent survey of foreign policy and global health experts conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that a “particular concern” among them was that investments that offered more immediate gratification would “always trump longer-term investments in systemic, sustainable solutions.”

Nor do experts see this troubling trend as fading anytime soon, even if the Ebola outbreak highlighted the flaws in a model where public health initiatives focused solely on eradicating or treating a single disease and showcased, in a most devastating way, the cost of neglecting basic public health infrastructure -- building clinics, laboratories and hospitals, or training nurses, doctors and other medical workers -- that could have benefits for public health that extend beyond stopping the spread of diseases like Ebola.

“There’s a tension that existed for a long time between achieving a specific goal related to a specific disease and building up a basic healthcare system,” said Josh Michaud, associate director for Global Health Policy at Kaiser Family Foundation. “That tension will continue.”

A Question of Branding

One of the biggest obstacles to attracting more funding and attention to broader public health schemes could actually be a marketing problem.

“It’s much easier to rally people around the idea of eradicating or saving lives from a particular disease,” Michaud said, pointing to the HIV epidemic as an example. Activists and policymakers helped turn HIV and AIDS into veritable cause. “You don’t get the same kind of emotional attention to building healthcare infrastructure,” he said. “No one’s been able to solve that problem yet of making primary healthcare sexy enough to the people who decide how to spend the money.”

End of #Ebola: lessons have to be learned; straying vigilant is a must; monitoring continues; map by @eu_echo #ERCC pic.twitter.com/H066yfSy9a

— ApostolosNikolaidis (@ap_nikolaidis) January 14, 2016And when it comes to Ebola, the virus also has an undeniable scare factor, conjuring images of people bleeding from their eyes and pores -- even if that happens only in a minority of cases -- that diverts attention away from public health measures that would guard against the disease and toward finding a cure or a vaccine.

“It is a very vivid and physically frightening disease,” said Dorie Clark, a marketing strategy consultant and the author of Stand Out. As a result, it appears “more urgent, to many people, than other diseases that may be insidious but not quite so visually arresting,” Clark said.

Diseases that similarly expose flaws in healthcare systems, like malaria, lower respiratory infections and diarrheal diseases, which together accounted for 39 percent of deaths in Liberia in 2010, attract less attention.

Years before the Ebola outbreak, Keith Martin, a physician who is now executive director of the Consortium of Universities for Global Health, in Washington, D.C., was in a rural part of Sierra Leone. Pharmacies had expired medications, he recalled, and when he stopped off at a clinic, the nurse there was sick.

“All she had were some rusty scissors, a concrete table and no running water,” Martin remembered. The clinic also lacked electricity. It was in this type of environment that the Ebola epidemic flourished -- and yet what continues to draw the most attention is the disease itself.

“As horrible and tragic as the Ebola crisis was, in West Africa, many more people died of non-Ebola causes while the outbreak was taking place," Martin said. "But no one talks about that."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.