How Worried Should You Be About Coronavirus Variants? A Virologist Explains His Concerns

Spring has sprung, and there is a sense of relief in the air. After one year of lockdowns and social distancing, more than 171 million COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered in the U.S. and about 19.4% of the population is fully vaccinated. But there is something else in the air: ominous SARS-CoV-2 variants.

I am a virologist and vaccinologist, which means that I spend my days studying viruses and designing and testing vaccine strategies against viral diseases. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, this work has taken on greater urgency. We, humans, are in a race to become immune against this cagey virus, whose ability to mutate and adapt seems to be a step ahead of our capacity to gain herd immunity. Because of the variants that are emerging, it could be a race to the wire.

Five variants to watch

RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 constantly mutate as they make more copies of themselves. Most of these mutations end up being disadvantageous to the virus and therefore disappear through natural selection.

Occasionally, though, they offer a benefit to the mutated or so-called genetic-variant virus. An example would be a mutation that improves the ability of the virus to attach more tightly to human cells, thus enhancing viral replication. Another would be a mutation that allows the virus to spread more easily from person to person, thus increasing transmissibility.

None of this is surprising for a virus that is a fresh arrival in the human population and still adapting to humans as hosts. While viruses don’t think, they are governed by the same evolutionary drive that all organisms are – their first order of business is to perpetuate themselves.

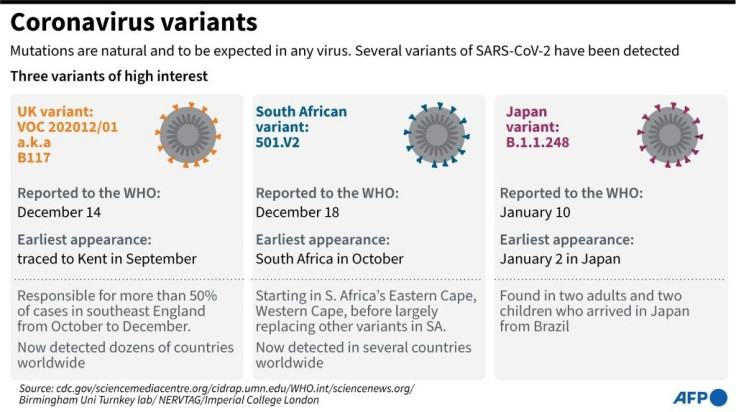

These mutations have resulted in several new SARS-CoV-2 variants, leading to outbreak clusters, and in some cases, global spread. They are broadly classified as variants of interest, concern or high consequence.

Currently there are five variants of concern circulating in the U.S.: the B.1.1.7, which originated in the U.K.; the B.1.351., of South African origin; the P.1., first seen in Brazil; and the B.1.427 and B.1.429, both originating in California.

Each of these variants has a number of mutations, and some of these are key mutations in critical regions of the viral genome. Because the spike protein is required for the virus to attach to human cells, it carries a number of these key mutations. In addition, antibodies that neutralize the virus typically bind to the spike protein, thus making the spike sequence or protein a key component of COVID-19 vaccines.

India and California have recently detected “double mutant” variants that, although not yet classified, have gained international interest. They have one key mutation in the spike protein similar to one found in the Brazilian and South African variants, and another already found in the B.1.427 and B.1.429 California variants. As of today, no variant has been classified as of high consequence, although the concern is that this could change as new variants emerge and we learn more about the variants already circulating.

More transmission and worse disease

These variants are worrisome for several reasons. First, the SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern generally spread from person to person at least 20% to 50% more easily. This allows them to infect more people and to spread more quickly and widely, eventually becoming the predominant strain.

For example, the B.1.1.7 U.K. variant that was first detected in the U.S. in December 2020 is now the prevalent circulating strain in the U.S., accounting for an estimated 27.2% of all cases by mid-March. Likewise, the P.1 variant first detected in travelers from Brazil in January is now wreaking havoc in Brazil, where it is causing a collapse of the health care system and led to at least 60,000 deaths in the month of March.

Second, SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern can also lead to more severe disease and increased hospitalizations and deaths. In other words, they may have enhanced virulence. Indeed, a recent study in England suggests that the B.1.1.7 variant causes more severe illness and mortality.

Another concern is that these new variants can escape the immunity elicited by natural infection or our current vaccination efforts. For example, antibodies from people who recovered after infection or who have received a vaccine may not be able to bind as efficiently to a new variant virus, resulting in reduced neutralization of that variant virus. This could lead to reinfections and lower the effectiveness of current monoclonal antibody treatments and vaccines.

Researchers are intensely investigating whether there will be reduced vaccine efficacy against these variants. While most vaccines seem to remain effective against the U.K. variant, one recent study showed that the AstraZeneca vaccine lacks efficacy in preventing mild to moderate COVID-19 due to the B.1.351 South African variant.

On the other hand, Pfizer recently announced data from a subset of volunteers in South Africa that supports high efficacy of its mRNA vaccine against the B.1.351 variant. Other encouraging news is that T-cell immune responses elicited by natural SARS-CoV-2 infection or mRNA vaccination recognize all three U.K., South Africa, and Brazil variants. This suggests that even with reduced neutralizing antibody activity, T-cell responses stimulated by vaccination or natural infection will provide a degree of protection against such variants.

Stay vigilant, and get vaccinated

What does this all mean? While current vaccines may not prevent mild symptomatic COVID-19 caused by these variants, they will likely prevent moderate and severe disease, and in particular hospitalizations and deaths. That is the good news.

However, it is imperative to assume that current SARS-CoV-2 variants will likely continue to evolve and adapt. In a recent survey of 77 epidemiologists from 28 countries, the majority believed that within a year current vaccines could need to be updated to better handle new variants, and that low vaccine coverage will likely facilitate the emergence of such variants.

What do we need to do? We need to keep doing what we have been doing: using masks, avoiding poorly ventilated areas, and practicing social distancing techniques to slow transmission and avert further waves driven by these new variants. We also need to vaccinate as many people in as many places and as soon as possible to reduce the number of cases and the likelihood for the virus to generate new variants and escape mutants. And for that, it is vital that public health officials, governments and non-governmental organizations address vaccine hesitancy and equity both locally and globally.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.

Paulo Verardi is an Associate Professor of Virology and Vaccinology at the University of Connecticut.