Huge Challenges Await Nigeria's New Military Chiefs

Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari's sudden replacement of his top military commanders may be a welcome change in a country frustrated over a decade-long insurgency, but on the ground, soldiers face a complex mix of conflicts.

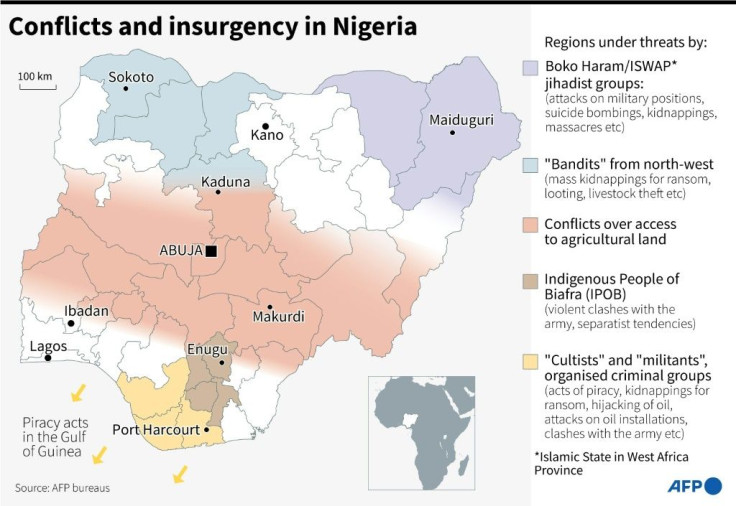

Often described as overstretched and underfunded, Nigeria's military is fighting jihadists in the northeast and armed gangs in the northwest as well as dealing with communal conflicts in central regions, separatist tensions in the southeast and piracy in the nearby Gulf of Guinea.

"Nigeria is in a precarious situation," Ikemesit Effiong, head of research at SBM Intelligence, a geopolitical consultancy firm, told AFP. "Every part of the country is dealing with a near-existential security challenge."

Nigeria has ongoing military operations in 35 out of the country's 36 states, he said.

After years of pressure, even from some allies, Buhari on Tuesday appointed a new chief of defence staff and new army, navy and airforce commanders in what experts said was a bid to breathe new life into the top military ranks.

For Bulama Bukarti, Africa analyst at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, the overhaul won't bring overnight change but is a key first step.

"We've seen troops losing confidence in their leadership, and we know Nigerians have lost confidence... and in a war, morale and public support are as important as the actual war on the ground."

In Maiduguri, the northeastern city at the heart of the insurgency, many residents greeted the news with renewed hope for change.

"It is a day of celebration in Maiduguri, everyone is happy about the new development," Kyari Sherif, a businessman in the city told AFP.

At least 36,000 people have died since the insurgency began and many residents in the city have witnessed the violence first hand.

Boko Haram and the Islamic state affiliate ISWAP control large rural areas and roads in the region, where they kidnap and kill soldiers, civilians and NGO workers.

"There needs to be a complete review of the counter-insurgency strategy," said Idayat Hassan of the Abuja-based think tank, the Centre for Democracy and Development.

In 2019, the army launched its "super camps strategy", reducing the number of smaller bases and fortifying larger ones in an attempt to limit exposure of troops on the ground.

"They were trying to reduce military fatalities but it gave insurgents more freedom of movement," said Bukarti.

"If that doesn't change, the insurgents will continue to wreak havoc in rural areas and mount checkpoints on roads."

The northeast is far from the only challenge the new commanders face.

In the northwest, criminal gangs known locally as "bandits" have terrorised communities for years, kidnapping, raping and pillaging.

In a security embarrassment last month, gunmen abducted 340 school students in Buhari's own home state of northwest Katsina, while he was visiting the area. The students were later released but the incident sparked outrage.

In the central Middle Belt region, long-standing rivalry over land between Muslim herders and Christian farmers continues to fuel intercommunal conflict.

And in the southeast, separatists militias appear to be regaining momentum, sparking tensions between the local population and government forces in an area with a history of attempts to carve out independence for the Igbo people.

In the nearby oil-rich Niger Delta, a mix of poverty and corruption led to the emergence of militant groups two decades ago demanding a greater share of petroleum wealth.

More recently, some have turned to piracy, launching attacks on commercial vessels in the Gulf of Guinea, kidnapping sailors and holding them for ransom in camps in the Niger Delta.

Last year, the Gulf of Guinea accounted for 95 percent of all hostages taken in 22 separate attacks on vessels, according to the International Maritime Bureau's Piracy Reporting Centre.

"Nigeria will be required to make some fairly significant strategic choices around where its priorities lie," Munro Anderson, partner at Dryad Global, a maritime security risk management firm, told AFP.

"With 80 percent of Nigerian trade conducted in the maritime domain, Nigeria, at both a political and security level, faces a tough choice between the securitisation of its vital trade routes or the securitisation of the northern political heartland."

Among the new appointments are Major-General Leo Irabor as chief of defence staff and Major-General Ibrahim Attahiru as army chief, both seen as experienced field commanders.

Their successes or failures could have wide-reaching consequences: insecurity across Nigeria means that businesses are highly concentrated in Lagos, the economic hub, further deepening inequality.

Most people have no choice but to live in areas that are unsafe.

"People can't farm, can't work their crops, and that has implication on poverty rates," said SBM Intelligence analyst Effiong. "Insecurity has a wider social and political cost."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.