Human Jaw Evolution Traced To Extinct Armored Fish Found In China

While the understanding that all life on Earth originated in water is commonplace, a lot of the details of evolution of specific anatomical features from primitive to modern are still not well understood. But the study of the fossil of a fish that lived about 423 million years ago may dramatically improve our knowledge of the evolution of at least one important body part: the jaw.

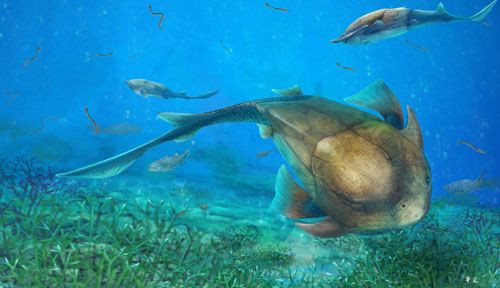

Qilinyu rostrate was an armored bottom-dwelling fish that lived in the Silurian period, from about 444 million years ago to about 419 million years ago. A fossil of the primordial fish was recovered from the Silurian Kuanti formation of Qujing, Yunnan province, China. It is a member of an extinct group of fish called placoderms whose heads and bodies were mostly covered in armor, with jaws that had bony plates, called gnathal plates, which acted like teeth.

Placoderms were also the first vertebrates to have jaws, but they still had no teeth, which appeared in later fish. Before placoderms, fish had sucker-like mouths. Vertebrae themselves only appeared over half a billion years ago, all life before then being invertebrate.

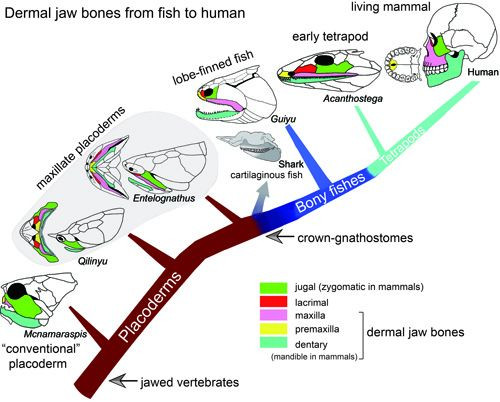

The jaw present in most modern vertebrates (sharks and rays are two notable exceptions) have some common features, in terms of bone structure. These are the maxillary, premaxillary and dentary bones. The first two are in the upper jaw while the third is in the lower.

Qilinyu and Entelognathus — another placoderm from the same period found in 2013 in the same region — exhibit the first instance of distinct maxillary, premaxillary and dentary bones. Through other physical features, they also show a connection between jawless fish and placoderms, which were previously considered unrelated.

The study of the placoderms further reveals that elements of the modern jaw first appeared in them.

Professor Per E. Ahlberg of Uppsala University in Sweden, who co-authored the study, said in a statement: “The simplest interpretation of the observed pattern is that our own jaw bones are the old gnathal plates of placoderms, lightly remodeled.”

The study, carried out by a team of researchers from China and Sweden, was published Thursday under the title “A Silurian maxillate placoderm illuminates jaw evolution” in the journal Science.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.