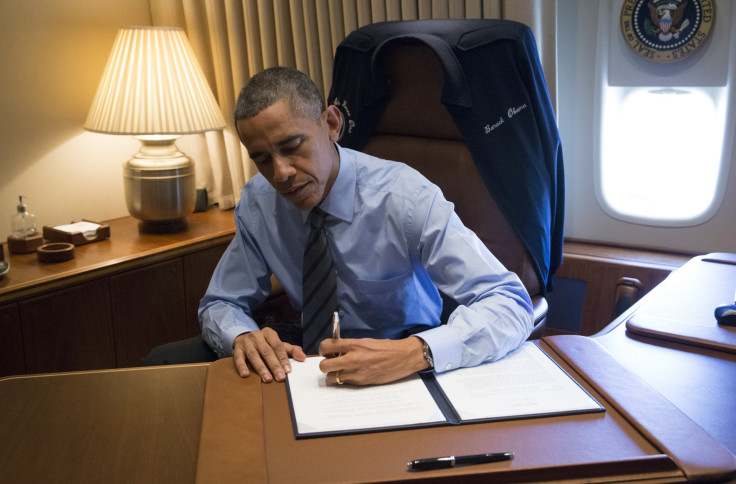

Immigration Reform 2014: Will Obama's New Immigration Enforcement Plan Fix Secure Communities' Problems?

President Obama’s executive action on immigration will likely dramatically alter the lives of some 5 million people who will soon be eligible for temporary deportation relief. But for nearly 7 million undocumented immigrants who won’t qualify for protection, their fate will lie largely in the hands of the administration’s new enforcement scheme, the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP).

Deportation relief remains the most far-reaching and politically sensitive part of Obama’s executive action package unveiled last week. But the end of Secure Communities, the widely criticized federal immigration enforcement program tasked with rooting out deportable criminals, and the emergence of PEP, is at the heart of what Obama said was a focus on deporting “felons, not families” and “criminals, not children.” While analysts say it will take time to see if PEP rectifies the problems Secure Communities presented, there is tentative hopefulness about the new program.

“This is the most significant step forward [in immigration enforcement] on trying to focus on real threats to communities that I’ve seen during the entire Obama administration,” said Ben Johnson, executive director of the American Immigration Council. “I’m cautiously optimistic that there’s a commitment to focus their resources on real criminals, that they’re finally getting it.” While part of the new program is based on branding, he said, “a lot of it is substance.”

Under Secure Communities, which became deeply unpopular during its six-year run, local law enforcement shared fingerprint data of people booked in local jails with the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency, which would in turn use that information to locate and deport immigrants with criminal violations. But over the years, the program became known for sweeping up immigrants with low-level offenses, such as traffic violations, as well as those never charged with any crimes, into deportation proceedings. The result, immigration advocates said, was a collapse of trust between communities and law enforcement.

Local mayors and governors also soured on the program: Over the past year nearly 300 jurisdictions across the country have passed laws limiting their cooperation with ICE and requiring that local law enforcement only turn over immigrants with serious criminal convictions or a judge-issued warrant to ICE authorities.

Department of Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson has himself admitted Secure Communities’ shortcomings. “The reality is the program has attracted a great deal of criticism, is widely misunderstood and is embroiled in litigation; its very name has become a symbol for general hostility toward the enforcement of our immigration laws,” he wrote in a memo detailing the end of the program last week.

PEP will continue to allow local police and ICE to share fingerprint data of immigrants booked in jail, but under the new scheme, only those with actual criminal convictions can be targeted for deportation. “By moving to a post-conviction model, it takes one of the encouragements of racial profiling out of [the program],” said Mark Fleming, national litigation coordinator for the National Immigrant Justice Center. The focus on convicted criminals could slash the number of immigrants transferred over to ICE custody by as much as 50 percent, he said.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that PEP will focus only on deporting serious, violent criminals. One of the priority categories for deportation laid out by the Department of Homeland Security includes immigrants convicted of an “aggravated felony,” a broad class of crimes under federal immigration law. While the term originally covered murder, federal drug trafficking and trafficking of specific types of arms, over the years it has enveloped lesser crimes such as petty theft, perjury, forgery and tax evasion.

“Unfortunately, immigration law continues to be a huge problem in focusing on really bad actors because the definitions under immigration law have been expanded so dramatically,” Johnson said. “In the interest of focusing on the worst of the worst, you’re going to continue to run into the ridiculously broad definitions under immigration law until Congress changes it.”

Former ICE director John Morton issued a series of memos in 2011 directing agents to exercise discretion in deciding which immigrants to target for deportation, taking threats to public safety and community ties in the U.S. into consideration. But it's still largely up to ICE agents to utilize that discretion.

While Homeland Security’s plans look promising on paper, Fleming said, ensuring that ICE agents adhere to the new rules will perhaps be the most crucial step in fixing Secure Communities’ problems. “The reality is that ICE has established over the last decade a certain culture, which is that removals are the priority and the only priority, period. And people that get the most removals get promoted,” he said. “How they change the culture of the place is almost going to be more important than the exact details [of the program].”

Meanwhile, Department of Homeland Security is also tackling another controversial aspect of the enforcement scheme: immigration detainers. When ICE targets someone for deportation, it sends a detainer request to local law enforcement asking it to hold the person in jail for up to 48 hours to be transferred into ICE custody. But in practice, many immigrants have been held for days or weeks past their release dates, provoking lawsuits and court rulings that have held the county itself liable for damages. According to Secretary Johnson’s memo released last week, ICE will now replace detention requests with requests for notification when a particular immigrant is about to be released from jail. Only in “special circumstances” will ICE send a detention request -- but the department hasn’t yet specified what those circumstances might look like.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.