India Disaster Highlights Pressure On Asia's Great Rivers

A glacial burst that triggered a deadly flash flood in the Indian Himalayas at the weekend was a disaster waiting to happen, and one likely to be repeated in a region transformed by climate change and unchecked infrastructure development, experts warn.

Asia is home to some of the world's biggest waterways, from the Ganges and the Indus in India to the Yangtze and Mekong originating in China, that snake for thousands of kilometres.

They support the livelihoods of vast numbers of farmers and fishermen, and supply drinking water to billions of people, but have come under unprecedented pressure in recent years.

Higher temperatures are causing glaciers that feed the rivers to shrink, threatening water supplies and also increasing the chances of landslides and floods, while critics blame dam building and pollution for damaging fragile ecosystems.

"Rivers are really at risk from development projects, dumping of solid waste and liquid waste, sand mining and stone mining," Himanshu Thakkar, from the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People, told AFP.

"Climate change is a longer-term process that has already set in. The impacts are already happening.

"So in every respect, rivers are under greater threat."

The disaster in India was apparently triggered by a glacial burst, that unleashed a wall of water which barrelled down a valley in Uttarakhand state, destroying bridges and roads and hitting two hydroelectric power plants.

Dozens have been killed and more than 170 others are missing after the accident on the Dhauliganga river, which feeds into the Ganges.

It is not yet clear what damaged the glacier and triggered the accident, but there are suspicions that construction of hydro-power projects -- in an area that is highly seismically active -- may have contributed.

"This area is prone to vulnerability, it is not appropriate for this kind of bumper-to-bumper hydro-power development," Himanshu said.

"Proper planning, impact assessment, proper geological assessment -- this has not happened here."

Patricia Adams, executive director from Canada-based environmental NGO Probe International, said dam building in such an area was simply too dangerous, as it makes hillsides unstable and causes landslides.

Some have also pointed to rising temperatures as a contributing factor.

A major study in 2019 suggested Himalayan glaciers had melted twice as fast since the turn of the century as in the 25 preceding years.

"The impacts of climate change in the Himalayas are real," said Benjamin P. Horton, director of the Earth Observatory of Singapore.

As well as greater danger of accidents, glacier loss in the Himalayas deprives local communities of water to drink and for agriculture, he said.

There have been other flooding disasters in the region in recent years. In 2013, some 6,000 people died when flash floods and landslides swept away entire villages in Uttarakhand as rivers swollen by monsoon rains overflowed.

In neighbouring China, flooding has also worsened on major rivers.

Last year the Yangtze, Asia's longest waterway, suffered record deluges that killed hundreds of people and submerged thousands of homes, with environmentalists saying it indicated climate change impacts were growing.

China has also built a vast dam network, although authorities insist this infrastructure helps mitigate flooding rather than adding to the problem.

Like in India, this has proved controversial, with some blaming the structures for contributing to earthquakes and landslips.

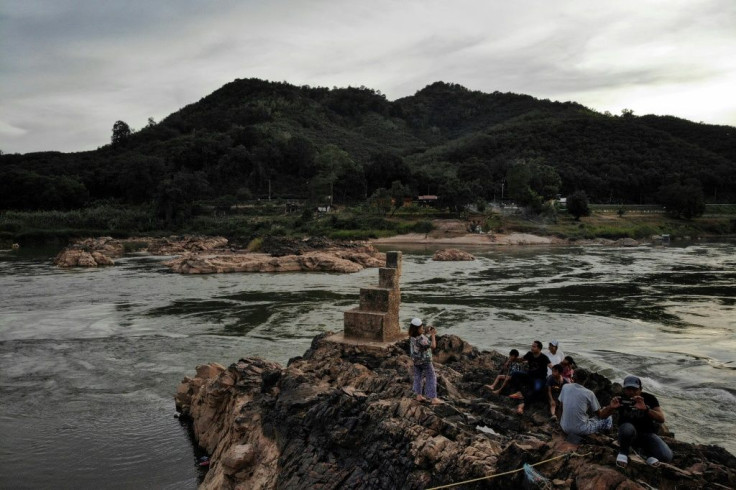

Beijing's dam building has faced criticism outside the country particularly on the Mekong River, which begins on the Tibetan Plateau in China and winds through Southeast Asia.

Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam all battled severe drought in 2019, as the tide of the river fell to record lows.

While some pointed to climate change, there were also calls for China to be more transparent about its dam operations -- Beijing has constructed 11 dams on its section of the river.

In downstream countries, dozens of hydro-power dams have been built or are planned -- many funded by Chinese-backed companies -- sparking concerns about environmental damage.

Some see sinister motives in Beijing's Mekong dam building.

The Chinese Communist Party "now control some of the mightiest rivers in the world on which millions and millions of people in downstream neighbouring countries depend for their food, their agriculture, and shipping, and their security", said Adams from Probe International.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.