Iran: Sixty Years After The 1953 CIA Coup That Toppled Democracy

The election of a moderate new president in Iran, Hassan Rouhani, who has promised to enact reforms, including the release of political prisoners, comes almost exactly 60 years after a cataclysmic episode that continues to define geopolitical relations in the Middle East and profoundly influence the image of the United States in the region.

It was a complex drama that involved Iran, Britain the U.S. and the Soviet Union -- and created an intractable dilemma that shapes international relations to the present day.

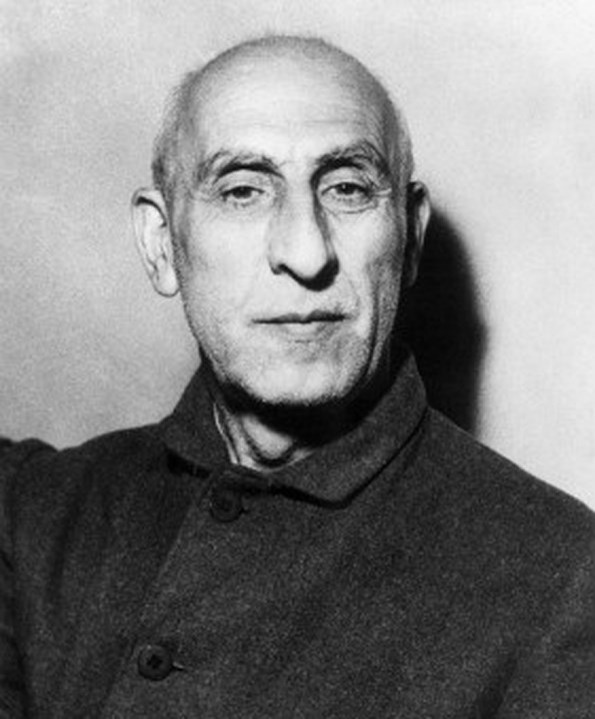

In August 1953, through the auspices of the U.S. CIA and British intelligence, in cooperation with forces loyal to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, the popularly elected prime minister of Iran, a man named Mohammad Mosaddegh was forcibly removed from power.

Following clashes between the police, military and pro-monarchy elements on one side and Mossadegh supporters on the other, which killed hundreds of people, Mossadegh was placed under arrest. In his place, retired General Fazlollah Zahedi, blessed with the endorsement of the Shah, named himself the new prime minister.

U.S. and UK intelligence officers had their fingerprints all over this forced “regime change” in Iran.

Mossadegh's “crime” had been to support the nationalization of Iran's key petroleum industry -- a grave affront to British oil company interests. The 1953 coup not only ended Iran's attempt to control its own hugely lucrative energy sector, but likely also killed any chances for Iran developing into a democratic society at that time.

Twenty-six years later, the outraged Iranian people would overthrow the Shah himself -- with the bitter memories of 1953 prominently on the minds of his determined opponents.

What occurred in 1953 planted the seeds of anti-American hatred in Iran and across the Middle East.

Initially, Mossadegh was himself appointed by the Shah and may have been viewed as a strong bulwark against a communist takeover of Iran (which might have been launched by Tudeh, Iran's communist party, which was in league with Moscow).

Britain, in particular, had a heavy presence in Iran, having occupied the country during the Second World War in order to control the oil routes going to Russia (then an ally) and to prevent the German Nazis from seizing the oil. Indeed, the British and Russians conspired to remove Reza Shah in 1941 out of fear that he sympathized with the Germans and replaced him with his son, the more malleable Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi.

After the war, Britain controlled Iranian oilfields through its ownership of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company -- the predecessor of British Petroleum (NYSE: BP). By 1951, when Iran’s parliament and Mossadegh sought to nationalize the oil industry, British intelligence concocted a plan to oust Mossadegh. The UK also imposed a global boycott on Iranian oil in order to economically pressure the country (a tactic that would be used decades later, but for other reasons).

In tandem with U.S. intelligence, the Western powers selected General Zahedi to engineer the coup, apparently with the support of a reluctant and indecisive new shah. (Ironically, Zahedi had been imprisoned in the 1940s by the British for his attempts to establish a pro-Nazi government in Iran.)

Mossadegh, who 30 years before the coup opposed the ascension to the throne of the shah’s father, was arrested for treason, spent three years in prison and remained under house arrest until his death in 1967.

Historian Ervand Abrahamian has written: “If Mosaddegh had succeeded in nationalizing the British oil industry in Iran, that would have set an example and was seen at that time by the Americans as a threat to U.S. oil interests throughout the world, because other countries would do the same.”

While Mossadegh was a highly eccentric and somewhat controversial figure on his own, his removal from power created in Iran a suspicion of the West -- particularly the United States -- that has never really abated.

The Shah of Iran moved from being a constitutional monarch with limited powers to an authoritarian ruler dependent on heavy financial and military support from the U.S. The CIA even trained Savak, the shah’s brutal secret police force.

The coup could be viewed as a temporary success, because it guaranteed the British and Americans easy access to Iran’s gigantic oil reserves for decades and it prevented Iran from falling under the influence (and possible control) of its looming communist neighbor, the Soviet Union.

But longer term, as illustrated by the coup against the shah in 1979 and the continued enmity between Tehran and Washington, the 1953 overthrow of Mossadegh created a much larger and more dangerous problem: the hostility of Iranians (and much of the Middle East) to the United States that concurrently led to the spread of Islamic militancy.

Former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright once regretted the coup and its aftermath. “The Eisenhower administration believed its actions were justified for strategic reasons,” she said. “But the coup was clearly a setback for Iran's political development. And it is easy to see now why many Iranians continue to resent this intervention by America in their internal affairs.”

In a book called “All the Shah’s Men,” author Stephen Kinzer wrote: “It is not farfetched to draw a line from [the 1953 coup] through the shah's repressive regime and the Islamic Revolution to the fireballs that engulfed the World Trade Center in New York.”

It was not until 2009 when the president of the United States explicitly referred to the American government’s complicity in the 1953 coup.

Speaking in Cairo, Egypt, Barack Obama declared: “In the middle of the Cold War, the United States played a role in the overthrow of a democratically elected Iranian government. ... For many years, Iran has defined itself in part by its opposition to my country, and there is indeed a tumultuous history between us.”

In a conciliatory gesture to Tehran, Obama added: “Since the Islamic Revolution, Iran has played a role in acts of hostage-taking and violence against U.S. troops and civilians. This history is well-known. Rather than remain trapped in the past, I have made it clear to Iran's leaders and people that my country is prepared to move forward.”

Now, six decades after the tumultuous events of the 1953 coup, the U.S. likely hopes that Rouhani opens a new peaceful and conciliatory chapter in Washington-Tehran relations.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.