James Webb Space Telescope: NASA Says It’s Close To Identifying Source Of Dec. 3 Anomaly, Vibration Tests To Resume Soon

In December, while conducting a “vibration test” on the James Webb Space Telescope — Hubble’s bigger and better successor that is to be launched late next year — engineers at NASA detected some anomalous readings. This prompted NASA to put further tests on hold until the cause of the unexpected response had been determined.

On Tuesday, NASA announced that it had since carried out three low-level vibration tests of the telescope — currently housed in a clean room at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland — and was now close to determining the cause of the anomaly.

“Currently, the team is continuing their analyses with the goal of having a review of their findings, conclusions and plans for resuming vibration testing in January,” Eric Smith, the program director for NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said in a statement.

Vibration tests — one of the many tests space-bound instruments are subjected to — are performed to ensure that spacecraft fit enough to tolerate the often hostile conditions they would have to face in space. These tests, along with acoustic tests, are also needed to ensure that hardware functionality is not impaired during severe launch and landing events.

During one such routine test on Dec. 3, accelerometers attached to the James Webb telescope detected unexpected responses, and the test shut itself down to protect the hardware.

“The Webb telescope is the most dynamically complex test article ever tested at Goddard, so the responses were a bit different than expected,” Paul Geithner, deputy project manager – technical, for the Webb telescope at the Goddard Space Flight Center, said in the statement. “This is why we test — to know how things really are, as opposed to how we think they are.”

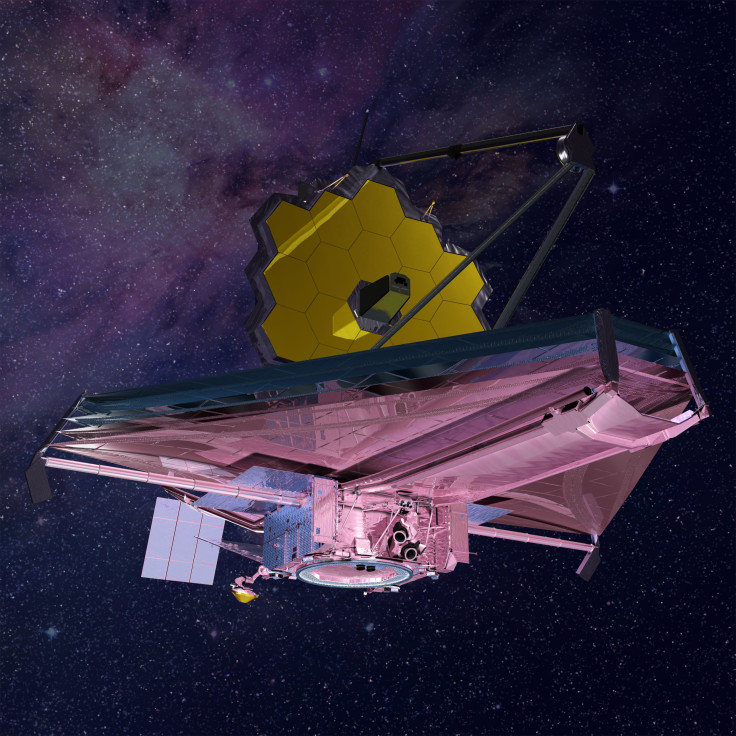

The James Webb Space Telescope, whose construction was completed in November — 20 years after work on the project began — is the most powerful space telescope ever built by humans. Once in orbit, the telescope, whose primary mirror has a diameter of 6.5 meters, will replace the hardy Hubble, which has been in service since 1990.

“As the premier observatory for the next decade, the Webb telescope will be stationed 1 million miles (1.5 million km) from Earth – some four times farther away from us than the moon,” NASA said in a statement released in 2014. “[It] will be able to detect the light from the first galaxies ever formed and explore planets around distant stars. It will study every phase of our universe's history, ranging from the first luminous glows after the Big Bang, to the formation of planetary systems capable of supporting life on planets like Earth, to the evolution of our own solar system.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.