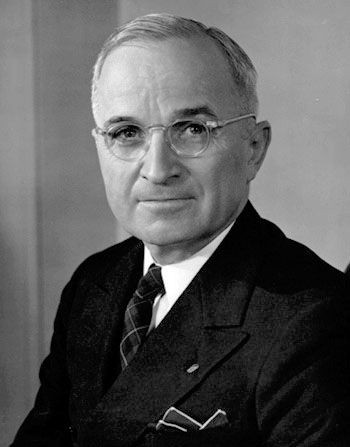

JFK Assassination: One Month After JFK’s Murder, Former President Harry Truman Called For Abolishing The CIA

Analysis

One month to the day after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, former President Harry Truman recommended that the U.S. abolish the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

In an op-ed column published in the Washington Post on Dec. 22, 1963, Truman never linked the CIA to President Kennedy’s murder, but the timing of the explicit and strongly worded column and complaint implied a connection.

“For some time I have been disturbed by the way the CIA has been diverted from its original assignment,” Truman wrote. “It has become an operational and at times a policy-making arm of the Government. This has led to trouble and may have compounded our difficulties in several explosive areas.”

Truman continued:

“This quiet intelligence arm of the President has been so removed from its intended role that it is being interpreted as a symbol of sinister and mysterious foreign intrigue -- and subject for cold war enemy propaganda,” the former president wrote.

Truman: No Distant Observer

Truman was no distant, uninformed public policy professional when it came to the CIA: In July 1947, then-President Truman signed into law the legislation that created the agency, which replaced the former U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

In 1944, William J. Donovan, the OSS’ creator, suggested to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that the nation should create a new, centralized organization/agency directly supervised by the president -- "which will procure intelligence both by overt and covert methods and will at the same time provide intelligence guidance, determine national intelligence objectives, and correlate the intelligence material collected by all government agencies."

Donovan also proposed that the new agency should have authority to conduct “subversive operations abroad.”

In December 1963, Truman articulated in no uncertain terms what he thought of the CIA’s covert operations dimension:

Truman said they should “be terminated.”

Later, in 1964, Truman would reiterate his call for removing covert operations from the CIA in a letter to Look magazine -- underscoring that he never intended the CIA to get involved in “strange activities” when he signed the legislation creating the institution.

Further, Truman is not the only high-profile U.S. public official to call for the abolition of the CIA’s operational activities. Former U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, D-N.Y., wanted to abolish the agency and transfer its intelligence functions to appropriate existing U.S. government departments. For example, weapons intelligence would be under the U.S. Department of Defense, political intelligence under the State Department and non-public economic intelligence under the Commerce Department.

What’s more, placing intelligence gathering and covert operations in separate government institutions helps prevent the government’s covert operations wing from influencing or distorting the intelligence-gathering wing’s reports to support its own goals. This separation addresses the inherent or at least potential conflict-of-interest problem that occurs when one institution is home to both research and operations functions.

Equally significant, placing the covert operations function in the U.S. Department of Defense would give the president more direct oversight of those operations than if they remain with the CIA. In other words, covert operations as part of the U.S. DOD -- whose secretary of defense regularly speaks with the president -- would improve their visibility and accountability via more-frequent policy reviews. It would also make it harder for an improvisational or rogue/unauthorized group in the department to create a “shadow operation” -- literally, an unauthorized covert foreign policy or para-military policy.

Truman: An Agency For Intelligence-Gathering Only

The risk of the potential creation of covert operations and para-military policies not authorized by and hidden from the U.S. president is at the core of Truman’s Dec. 1963 complaint about the CIA: By that point, the CIA had created numerous covert operations, missions and projects -- the sort of “strange activities” in which Truman never intended the CIA to get involved.

In other words, to Truman in Dec. 1963, the CIA was an agency that had run amok, and although the former president could have called for the end of the CIA’s operational duties at any time, the fact that he timed his complaint to be published one month after the JFK assassination is significant. At minimum, Truman’s column is an expression of his concern about a CIA that had strayed far from its creators’ intent. At maximum, Truman’s column -- published when a stunned nation was still grieving and exhibiting shock and confusion over JFK’s death, and as suspicions of a plot reverberated across America -- is one of the earliest expressions of doubt concerning the government's official narrative that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone and unaided to assassinate President Kennedy.

Further, the year-later release of the Warren Commission’s report on the JFK assassination -- which concluded that Oswald had acted alone in killing Kennedy with three rifle shots, and that Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby had acted alone in killing Oswald two days after Oswald’s arrest -- did little to dispel public concern that the report was implausible and unconvincing. In the months and immediate years that followed, assassination researchers would rebuke the Warren Commission for its grossly slipshod investigation procedures -- particularly for failing to collect 100 percent of the evidence, and for failing to analyze evidence it had collected -- and for other serious violations of basic protocols for criminal investigations.

Those doubts by the American people and by assassination researchers about the lone-gunman conclusion would increase in 1978, when a second investigation, the U.S. House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA), concluded that President Kennedy was very likely assassinated as a result of a plot/conspiracy. However, the committee was unable to identify the other gunmen or the extent of the conspiracy.

Making Public JFK Assassination Files Held By The CIA Would Clarify Much

Further, as noted, Truman’s complaint is not an indictment of the CIA in the aftermath of the tragedy that occurred in Dealey Plaza on Nov. 22, 1963 -- one of the darkest and most ignominious days in the nation’s history -- a day that changed the trajectory of both U.S. domestic and foreign policy.

That said, the U.S. intelligence community in general, and the Central Intelligence Agency specifically, could resolve many of the questions/anomalies that form the mystery at the center of this case -- and fill in the dozens of gaps left by the Warren Commission -- by making public more than 1,100 classified files related to the JFK assassination.

In particular, when made public, the classified files -- of CIA Officer George Joannides; CIA Officer David Atlee Philips, who was involved in pre-assassination surveillance of Oswald; Birch D O’Neal, who as counter-intelligence head of the CIA, opened a file on defector Oswald; and the files of CIA Officers Howard Hunt, William King Harvey, Anne Goodpasture, and David Sanchez Morales -- will help the nation determine what really happened in Dallas, who Oswald was and how the CIA handled Oswald’s file.

However, the CIA says the Joannides’ files and the files of the CIA officers -- which the Agency said are “not believed relevant” to the JFK assassination -- must remain classified until at least 2017, and perhaps longer, due to U.S. national security. But the CIA’s national security claim has never been independently verified, according to JFKFacts.org Moderator Jefferson Morley.

Morley v. CIA – An Attempt To Obtain The Full Truth

Morley is the plaintiff in the ongoing Morley v. CIA suit, which seeks to make public Joannides’ classified files.

In Morley’s suit, his attorney has responded to the CIA’s latest brief, on the issue of court fees. Having won on appeal twice, Morley argued that the standard practice of the U.S government paying court fees for a successful appeal should apply. The CIA countered that the litigation has not generated any significant new information, and therefore the government should not have to pay the court fees. The issue is now in the hands of U.S. Judge Richard Leon.

It must be underscored that, to date, there is no smoking gun or incontrovertible evidence of a plot or conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy, but there is a pattern of suspicious activity, along with a series of anomalies and a commonality of interests among key parties, that compel additional research and the release of non-public documents.

Further, the CIA probably is not covering up some tectonic, systemic crisis-triggering secret about the assassination of President Kennedy, or even evidence of a colossal Agency operational failure that would prompt the American people to call for a dismantling of the national security state apparatus.

However, until all of the JFK assassination files are made public, the pattern of suspicious activity, anomalies, and commonality of interests, along with the observations of the investigators and public officials -- including former President Harry Truman's Dec. 1963 call for the elimination of the CIA’s operational duties -- form a preponderance of evidence that strongly suggest that -- at minimum -- the American people do not know the full truth regarding the assassination of President Kennedy, and that the Agency is hiding something.

--

See Also:

4 JFK Assassination Files The CIA Must Make Public

In Dealey Plaza, It Is Always November 22, 1963

The CIA And Lee Harvey Oswald - Questions Remain

Just Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald?

First JFK Assassination Conspiracy Theory Was Paid For By The CIA

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.