Keystone XL And The Alaska Pipeline: Environmentalists Vs. Oil Industry; What Obama Can Learn From Nixon

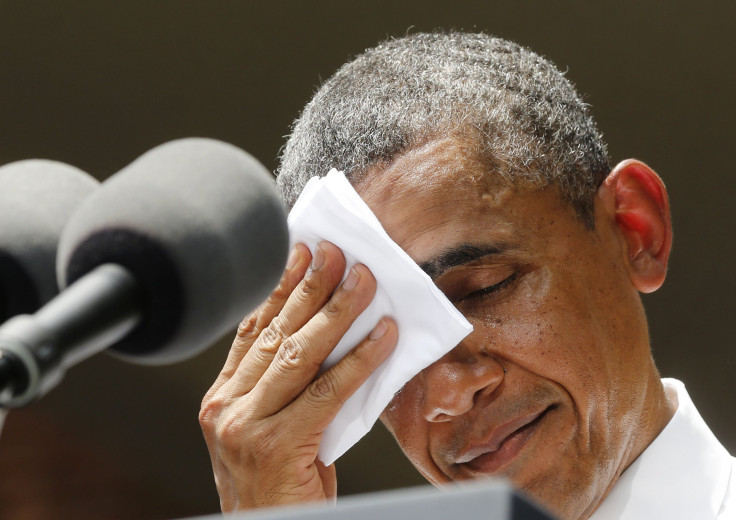

In his much-anticipated climate change speech in June, President Obama’s description of planet Earth was eloquent: “Beautiful; breathtaking; a glowing marble of blue oceans, and green forests, and brown mountains brushed with white clouds, rising over the surface of the moon.”

The imagery was as lovely and evocative as a desktop wallpaper photo from NASA, and in fact, Obama was describing an image taken by Apollo 8 astronauts on Christmas Eve 1968, during the first human orbit of the moon. That photo, the president noted, “would change the way we see and think about our world.” Astronaut James Lovell himself said of the image, “It makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth.”

The first view of the planet from outer space was, as the speechwriters say, Obama’s hook – the attractive lure to get his audience on board. Yet the context of the president’s speech was anything but tranquil and removed, coming as it did during one of the most intense and rancorous debates over energy and the environment in U.S. history. Down there amid those swaths of blue, green and brown, the debate has grown increasingly ugly, and Obama is clearly destined to have a hard time finding comfortable common ground with his opponents.

Pivotal to the debate is a controversial proposal to build a pipeline from Canada to the Midwestern town of Cushing, Okla., the busiest pipeline junction in the U.S. Among opponents and proponents of the Keystone XL pipeline, the question is whether the president was using his climate change speech to lay the groundwork for killing the project – something that he alone could do – or for letting it go through while putting in place other measures to placate environmental groups.

Obama has left everyone guessing on that. His climate change speech was all about finding a balance between exploiting strategic and lucrative commodities and ensuring that the environment is protected, if not left in a pristine state. Though he remains cagey about his plans for Keystone XL, history illuminates such matters; one need only look back 40 years to see the outcome of a similar debate over the then-controversial Trans-Alaska pipeline, begun in 1974 and completed in 1977. Environmental groups had every reason to believe they would prevail in halting the Alaska pipeline project, including court rulings in their favor. But in the end, politics won out. For Keystone opponents, it may be the ultimate cautionary tale.

Watch this clip to see how Obama channels Nixon on the environment: Both presidents have had difficulties in finding a policy on how best to protect the environment while tapping into energy resources.

If built, Keystone XL will span 1,179 miles and transport two types of crude oil from Alberta, Canada, and from North Dakota and Montana, to refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast, passing through the country’s pipeline hub in Cushing along the way. TransCanada, the Canadian energy company tasked with the construction, is waiting for the go-ahead from Obama, who has the authority to issue presidential approval and who has so far delegated to the State Department to determine whether building the pipeline is in U.S. national interests. Presidential approval is required because the project crosses an international boundary.

The primary controversy surrounding the pipeline stems from the environmental impacts associated with the extraction of oil sands in Alberta. Also referred to as tar sands, oil sands are permeated with bitumen, a form of petroleum in solid or semi-solid form that is blended in clay, sand and water. Environmental groups say the extraction method is more carbon-intensive than that of conventional crude, and the National Resources Defense Council claims that if the pipeline is approved it will add 1.2 billion metric tons of carbon pollution to the atmosphere during its 50-year lifespan.

Also of concern, as with the Alaska pipeline, are potential impacts on sensitive ecosystems along the pipeline route, as well as the possibility of pipeline accidents and oil spills. Lois Epstein, an engineer and pipeline safety expert and Arctic program director in the Alaska regional offices for The Wilderness Society, said there are unknown variables involving oil derived from tar sands, which have different viscosity than conventional crude. “There are some questions associated with what happens if you do have a spill -- what kinds of environmental differences are there with the cleanup,” she noted.

Not surprisingly, proponents say that the benefits of building the pipeline outweigh the environmental risks by reducing dependence on foreign oil from countries that do not have U.S. interests in mind.

The project will also create 20,000 jobs, according to TransCanada, which expects to spend $7 billion in the U.S. to build it.

Others say both sides have a point. “The local pollution coming from spills are real, and any time you build a new pipeline, you obviously increase the risk of a spill,” noted Christopher Knittel, professor of energy economics at the Sloan School of Management at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Experts like Knittel say that extracting oil sands is more energy-intensive and will lead to more greenhouse gas emissions per barrel of oil. But if the pipeline is not built, a commensurate volume of oil from other sources will take its place to meet the demand, Knittel said. The real question to be addressed, then, is how dirty Canadian tar sands are compared to other sources.

“There is good reason to believe that the oil that would replace [Canadian oil sands] would be Venezuela heavy oil, which is actually dirtier than Canadian tar sand oil,” Knittel said. Added to that, he said, is the risk of relying on Venezuela, whose current leadership is not exactly friendly toward the U.S. and could use oil exports as leverage against the country.

Proponents argue that as time passes, absent Keystone XL, TransCanada will look elsewhere to transport the tar sands oil; already, the company has received approval for an eastward-bound pipeline to transport crude from western Canada to eastern Canadian refineries and export terminals. The project, known as the Energy East pipeline, will be able to deliver more barrels of oil per day than the proposed Keystone XL pipeline.

All of which begs the question: What are the odds that Keystone XL will go through? That’s where several precedents set by the Alaska pipeline come into play.

The Trans-Alaska pipeline was the most controversial oil pipeline in U.S. history. Completed after years of debate in 1977, it enabled the extraction and transporting of oil from the icy, remote North Slope of Alaska to the port of Valdez. Beginning in 1968, environmentalists and proponents debated the project, primarily focusing on its impacts on the sensitive region that it would pass through. Also contentious was its effect on Native American tribes across whose lands it would pass.

In 1968, oil had been struck at Prudhoe Bay on the North Slope, the largest oil field ever discovered in North America. The question then became how to get the 10 billion barrels of oil out of Alaska and onto the market. By 1969, oil companies were making plans to build a pipeline through Alaska’s wilderness with a projected completion date in 1972.

However, it would take more than five years for the pipeline to be built because of environmental groups delaying the process.

The Wilderness Society, Friends of the Earth and the Environmental Defense Fund all joined in the fight against the construction of the pipeline, saying it would devastate the Alaska environment and associated fish and wildlife, disrupt migratory routes for caribou, and hold potential for serious oil spills, all while ignoring the needs of Native Alaskan tribes who controlled lands along the route.

In addition to crossing the Yukon River, about 75 percent of the terrain along the pipeline route is what is known as permafrost, which never thaws, requiring that the pipeline be built above ground or heavily insulated and/or buried in refrigerated ditches. Oil passing through the pipeline is hot and has the potential to melt the unstable permafrost, which could result in environmental damage as well as physical movement of the pipeline.

One of the tools that environmental groups used to fight the construction was the National Environmental Policy Act, commonly known as NEPA, which, in an ironic twist, was enacted by President Richard Nixon, who supported the construction of the pipeline.

On March 5, 1970, five Native villages in Alaska filed suit against oil companies and the U.S. Department of the Interior and its secretary, Walter Hickel, to stop the construction until Alaska Natives gave their consent.

In what seemed to be a two-pronged attack, 11 days later on March 26, the Wilderness Society, Friends of the Earth and the Environmental Defense Fund sued both oil companies and the Department of the Interior on grounds that the proposed pipeline violated both the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 and NEPA.

For companies building on federal land, which was the case in the Alaska pipeline, Interior needed to grant permits, and the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 restricted the width of rights of way for pipeline projects. The proposed Alaska pipeline exceeded the allowable width.

NEPA also required the creation of an Environmental Impact Statement for a proposed pipeline, and for considering alternatives that would reduce the environmental impacts. A limited EIS was done for the Alaska pipeline, which environmentalists said was not adequate.

Armed with these laws, environmental groups won an injunction against the entire pipeline project a month later. At the end of 1971 Nixon signed into law the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, which gave the right to select 44 million acres of land as well as a cash settlement of nearly $1 billion to Natives, eliminating that part of the debate.

On March 20, 1972, the DOI released the final EIS, which grew from an original 256 pages to a nine-volume comprehensive study on the environmental and economic impact of the pipeline. The release of the EIS was followed by a 45-day review period in which environmental groups went over before any decisions were made.

Then on May 11 in 1972, Rogers C. B. Morton, the new Interior secretary, granted rights of way for the pipeline, after which the case went back to a federal district court, where Judge George L. Hart ruled that Interior had complied with all the necessary regulations and construction could proceed.

Congress cleared the way for the project notwithstanding the court's conclusion that NEPA had not been satisfied.

On Feb. 9, 1973, an appeals court overturned the ruling, saying the first court had no jurisdiction over the right of way limits in the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920. Congress responded by revising the law itself, and on July 17, in a close vote of 50 to 49, the Senate narrowly passed an amendment declaring that Interior had fulfilled the requirements of NEPA. Spiro Agnew, vice president under Nixon, was the deciding vote.

The momentum for further opposition – legal or otherwise -- dwindled during the resulting Arab oil embargo, instituted on Oct.17, as a result of the Yom Kippur War. On Nov. 16, when Nixon signed into law the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act, the precedent was set: America could set aside environmental debate in the interest of energy independence.

“We stopped it, and then they [the government] ran around us,” Doug Scott, a 45-year veteran of the Wilderness Society, which fought against the construction of the pipeline, explained.

While environmental groups and Alaska Natives were unable to stop the pipeline, they were able to influence how it was built, and along they way they created a template for fighting other environmentally damaging projects, including Keystone XL.

The environmental success helped give NEPA some teeth, Scott said. Previously, NEPA had seemed a symbolic gesture, but now environmental groups recognized that they could force Interior to create environmental impact statements, and that they had legal power. In addition, environmental groups forced the elevation of the above-ground portions of the 800-mile pipeline to enable migratory caribou to pass through.

“One of the legacies of the Alaskan pipeline was making the environmental laws in the United States, notably the National Environmental Policy Act, infinitely stronger than anybody thought it was going to be,” Scott said.

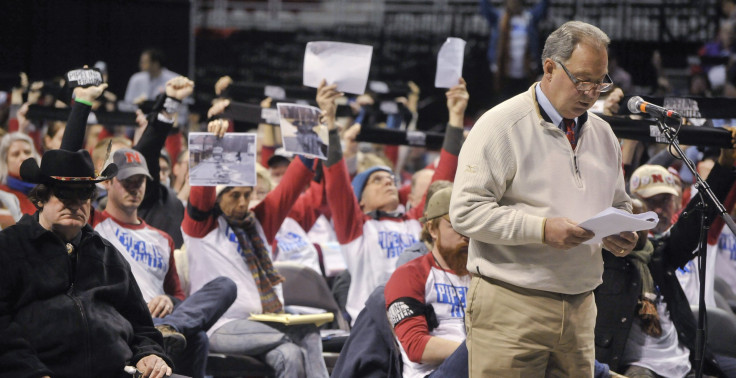

In many ways, the lobbying efforts, media campaigns and legal cases in the arsenal of Keystone opponents hark back to the Alaska pipeline controversy of the 1970s. In fact, the same groups fighting the Alaska pipeline in the '70s are now fighting Keystone. The new generation is using the same tools previous activists used, including invoking NEPA, and have so far succeeded – as their forbears did – in expanding the debate, delaying construction and forcing changes in the proposed route.

The one crucial area where Keystone diverges is the issue of greenhouse gas emissions. Though fossil-fuel pollution was beginning to be a concern at the time of the Alaska pipeline debate, climate change was not a part of the equation, and so Keystone XL has a slightly different cast.

Its construction is more directly linked to big – almost existential -- questions, which leave opponents little room for negotiation. How, after all, can the environmental impact of pumping and transporting tar sands be reduced? What is the fallback position, the compromise, for those who oppose the very use of the Canadian crude?

Because Keystone will cross the U.S.-Canada border, the U.S. State Department conducted the pipeline’s environmental impact statement in 2011, and the study concluded that there would be minimal environmental damage and that its construction was the “preferred alternative.”

Homeowners and environmentalists joined forces in the run-up to a decision on the pipeline to oppose the Keystone’s route in Nebraska, arguing that the route would run through the Sandhills region of Nebraska, under which flows a giant, shallow freshwater aquifer. In January 2012, President Obama acknowledged those concerns and rejected TransCanada’s application for a presidential permit; the company created a new route through Nebraska that satisfied the governor, Dave Heineman, who approved the change, and TransCanada reapplied for a presidential permit.

Obama, still under pressure from environmentalists concerning the intense process of extracting Canadian oil sands and other possible environmental impacts, delayed his final decision. TransCanada expected Obama to make a decision by this summer, but Obama instead focused on his Climate Change Action Plan, which crushed hopes that the project would begin by the second half of 2015. The State Department, meanwhile, continues to work on making a determination about whether the Keystone pipeline is in the national interest.

In his climate change speech, Obama said that his decision would be based on whether Keystone would contribute to producing more carbon emissions if it were built. Extracting tar sands is more energy-intensive because it involves a solid rather than liquid material.

“The net effects of the pipeline’s impact on our climate will be absolutely critical to determining whether this project is allowed to go forward. It’s relevant,” Obama said.

The State Department, which is required to delegate an environmental review to an independent third party, selected Environmental Resources Management (ERM). The conclusions by the State Department upon completion of ERM’s study said that Keystone would not significantly exacerbate carbon emissions and that if the pipeline was not built it was likely to be moved elsewhere.

Whether or not the Keystone pipeline is built, the Canadian crude will find its way out to the open markets.

“Keystone is not the driver of whether Canadian oil sands will be produced,” said TransCanada head Russ Girling. “They will be produced anyway.”

Like the debate surrounding the Alaska pipeline, where the U.S. as a whole was starting to address the need for protecting the environment, the Keystone pipeline is really the first step in addressing climate change, Anthony Swift, an attorney for Natural Resources Defense Council, said.

Others argue that Keystone XL is inevitable, regardless of what opposition groups say or do, and that in the end, the same was true of the Alaska pipeline.

The overarching question is how the pipeline fits into Obama’s climate change agenda, and his decision is fraught with political perils, as was Nixon’s on the Alaska pipeline, which pitted the nation’s nascent environment movement against fears about the Arab oil embargo. Nixon, despite his support for the Alaska pipeline and his significant political transgressions, managed to secure a place in history as an environmentally sensitive president.

“[Nixon] is correctly remembered as really one of the greatest environmental presidents, and that is not a very long list," Scott said. “Nixon properly deserves to be in that pantheon of environmental presidents.”

Obama’s legacy – as an environmentalist and otherwise – is still being formulated, and Keystone will likely be a factor. Environmental groups have delayed construction of Keystone primarily by exerting pressure on Obama, who will have to find a similarly complex route through sensitive political terrain. Many experts concede the odds of his killing the project are slim. Like Nixon, Obama will have to weigh whether the pipeline is in America’s national interest or not.

But as Obama delayed making a decision, and during his formulation of a climate change plan, Friends of the Earth revealed in July that ERM, the London-based consultant that the State Department hired to review the project, had lied on its disclosure form that it had no ties to entities with an interest in its completion. According to Friends of the Earth, ERM has worked with TransCanada as well as ExxonMobil, Shell and Chevron, all companies that would profit from the Keystone XL construction. That revelation has the potential to influence the politics of Obama’s decision and to raise questions about the credibility of the environmental study.

An investigation by the State Department’s inspector general into the conflict of interests and failure to follow screening guidelines has delayed the approval process for the pipeline until at least January. Meanwhile, TransCanada last week won a state appeals court ruling in Texas allowing it to lay the Keystone Gulf Coast pipeline, the second half of the Keystone XL pipeline that will bring oil down from Cushing.

Scott acknowledged that while environmentalists tends to be “incurably romantic” and idealistically believe they can stop Keystone, as they believed they could stop the Alaska pipeline, the odds are that the best they will be able to do is influence how it is built. And unlike the Alaska pipeline, how it is built may be less significant than the fact that it is built.

Swift, with the Natural Resources Defense Council, said the main issue behind the construction of Keystone XL is “whether it makes sense knowing what we know about climate change to permit a project that would significantly increase our carbon imprint.” Acknowledging what happened with the Tran-Alaska pipeline, he said, “past performances are not indicators of future results. I think there is a difference.” At issue now is climate change itself, he said, adding, “The campaign against Keystone XL is in a large way focused on beginning to address that.”

And in that way, Keystone could be an environmental bellwether, as the Alaska pipeline was before it -- causing significant changes in the way that we, as Obama noted, “see and think about our world.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.