Killing Charlie: The Attacks That Heralded France's Year Of Terror

"Nothing will ever be as before", predicted Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo after two gunmen massacred cartoonists at the Charlie Hebdo satirical magazine in Paris five years ago.

The attack on the weekly -- with its long history of mocking Islam and other religions -- was the first in a series of assaults that have claimed more than 250 lives since January 7, 2015, mostly at the hands of young French-born jihadists.

It sent shockwaves through France, exposing divisions in the multicultural modern Republic and sparking an intense debate about Muslim integration and press freedom.

The Kouachi brothers who killed 12 people in their strike on Charlie Hebdo claimed to be avenging the magazine's publication of cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed deemed offensive by many Muslims.

"We avenged the Prophet Mohammed. We killed Charlie Hebdo!", they shouted triumphantly as they ran through the streets.

Within three days, the death toll in the rampage of the al-Qaeda-affiliated siblings and accomplice Amedy Coulibaly had risen to 17, including four people at a kosher supermarket and three police officers.

The Kouachis failed in their bid to "kill" Charlie Hebdo; despite losing its top talent the magazine remained afloat thanks to an outpouring of solidarity.

"I wanted the paper to continue to exist. For me it couldn't just stop like that because of what happened," said Pierrick Juin, a cartoonist who joined the magazine just months after the attack.

This week the magazine published a defiant anniversary issue remembering the attack and also denouncing what it said was a new kind of politically correct censorship by those who "believe themselves to be the kings of the world behind their keyboard and smartphone."

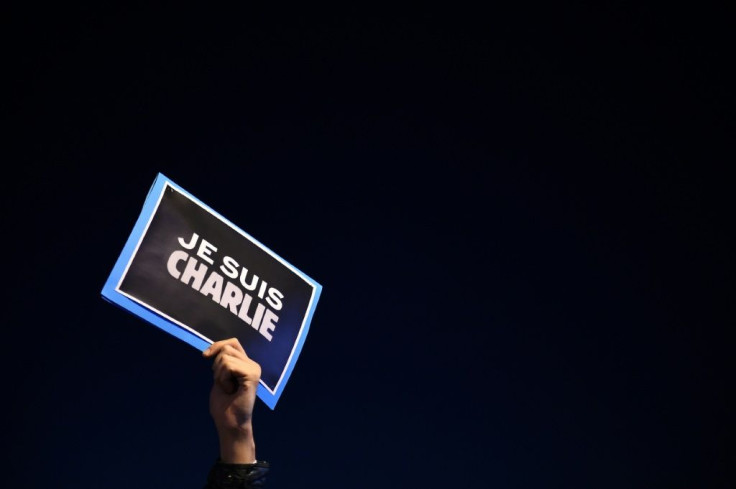

But the attacks did expose deep divisions in France: even a nationwide minute of silence observed by four million people under the slogan "Je suis Charlie" (I am Charlie) could not project a nation united in mourning.

Students at around 200 schools, many of them in neighbourhoods with big immigrant populations, boycotted the tribute, accusing Charlie Hebdo of Muslim-baiting.

Then prime minister Manuel Valls drew widespread criticism by linking the rise of extremism to France's "geographical, social and ethnic apartheid".

President Emmanuel Macron reprised the theme during his 2017 election campaign.

But despite his talk of ending the "house arrest" of young people trapped in high-rise suburban housing projects, the breeding grounds of several of the jihadists who have attacked France since 2015, their conditions remain largely unchanged.

A major Odoxa survey in November showed a majority of residents in housing projects still feeling abandoned by the state and discriminated against by employers.

The three days of attacks in January 2015 culminated in a deadly hostage-taking by Coulibaly at the Jewish supermarket, confirming fears that French Jews had become a top target for homegrown Islamist radicals.

Coming three years after an Islamist gunman shot dead a teacher and three children at a Jewish school in Toulouse, the attack compounded the feeling that "everywhere, at any time, we were a target," France's chief rabbi Haim Korsia told AFP.

For Korsia it marked "a sort of loss of innocence" in the 500,000-strong French Jewish community, Europe's largest, which had until then seen the biggest threat as being from the far right.

Jewish emigration to Israel hit a peak in 2014-15, years which also saw an exodus from the multi-ethnic French suburbs where Jews of north African origin had lived alongside Muslims for decades.

As the year wore on the attacks grew broader in scope, randomly targeting French people in November 2015, when Islamic State bombers and gunmen slaughtered 130 people in Paris.

But although departures for Israel have since declined, anti-Semitism is still on the rise, as the desecration of more than 100 graves at a Jewish cemetery in Alsace showed last month.

In the aftermath of the January 2015 attacks, then president Francois Hollande sent troops into the streets to guard vulnerable sites and patrol tourist hotspots.

Over the past five years, troops from the Sentinelle anti-terrorism operation have become part of the landscape in French cities.

The military presence was stepped up after the bloodshed of November 2015 and remains at a high level, with around 10,000 troops deployed.

France remains on its second-highest alert level, with sporadic attacks by individuals accused of having become radicalised continuing to claim lives.

In the latest deadly incident, a 22-year-old convert to Islam with psychological problems went on a stabbing rampage in a park near Paris on January 3, killing one man and injuring two women.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.