Lab-Grown Human Embryo Breakthrough Rekindles Debate Over 14-Day Research Limit

For the first time ever, researchers have been able to grow a human embryo outside the uterus for 13 days — a significant improvement over the previous record of nine days and a development that opens a new window into the hitherto little understood stages of human ontogenesis. However, the accomplishment puts research involving in vitro human embryos on a “collision course” with international regulations that places a 14-day limit on laboratory studies of embryos.

“This is about much more than just understanding the biology of implantation embryo development. Knowledge of these processes could help improve the chances of success of IVF [In Vitro Fertilization], of which only around one in four attempts are successful,” Simon Fishel, founder and president of the U.K.’s CARE Fertility Group, said in a statement.

Fishel is the co-author of one of the two studies published Wednesday, which describe the findings of the research.

One of the key findings of the study was the surprising discovery that the reorganization of the human embryo that normally takes place after it has implanted itself into the uterus can be achieved even in laboratory cultures.

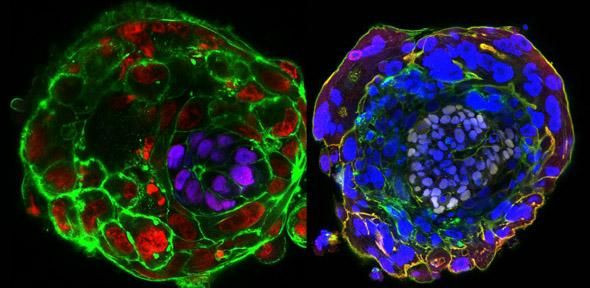

“Embryo development is an extremely complex process and while our system may not be able to fully reproduce every aspect of this process, it has allowed us to reveal a remarkable self-organising capacity of human blastocysts that was previously unknown,” Marta Shahbazi, a researcher at the University of Cambridge who co-authored one of the studies, said in a statement.

A blastocyst is a ball of cells that forms about three days after an egg has been fertilized by a sperm. This clump of cells then differentiates into tissues that later develop into organs.

Although the blastocyst stage of human embryos has been extensively studied and documented, what happens beyond the seventh day of fertilization — when the embryo must implant itself into the uterus to survive — still remains shrouded in mystery.

“Implantation is a milestone in human development as it is from this stage onwards that the embryo really begins to take shape and the overall body plans are decided. It is also the stage of pregnancy at which many developmental defects can become acquired. But until now, it has been impossible to study this in human embryos,” Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz from the University of Cambridge, who co-authored both the papers, said in the statement.

In addition to providing invaluable insights into the earliest stages of human development, the study also rekindles debate over the internationally-accepted rule, proposed in 1979 and adopted in the U.K. in 1984, that limits in vitro human embryo research to up to 14 days after fertilization.

“The 14-day rule was never intended to be a bright line denoting the onset of moral status in human embryos. Rather, it is a public-policy tool designed to carve out a space for scientific inquiry and simultaneously show respect for the diverse views on human-embryo research,” researchers, not involved in the study wrote, in a commentary for the journal Nature. “Some might conclude from such developments that policymakers redefine boundaries expediently when the limits become inconvenient for science. If restrictions such as the 14-day rule are viewed as moral truths, such cynicism would be warranted. But when they are understood to be tools designed to strike a balance between enabling research and maintaining public trust, it becomes clear that, as circumstances and attitudes evolve, limits can be legitimately recalibrated.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.