Life Under ISIS Siege, Syrian Regime Airstrikes: The Battle For Survival In Palmyra

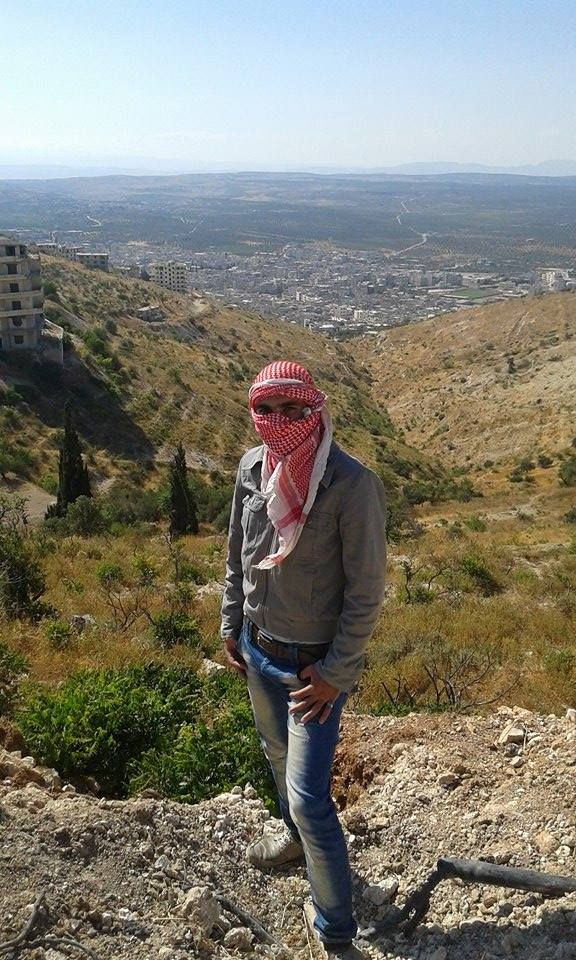

At a Syrian rebel base in the Idlib countryside, Mohammed Hassan al-Homsi has no way of knowing whether his siblings are still alive. Last week, he fearfully watched the Islamic State group's latest execution video, scanning the lineup on the steps of Palmyra's ancient ruins for faces he knew. His siblings were not among the victims, but he felt no relief at their absence. Al-Homsi knew the Syrian regime's retaliation for losing control of his hometown was imminent. The coming airstrikes would destroy much of the 3,000-year-old city and likely kill many of its residents. All he had left of Palmyra was the image of its blood-smeared ancient ruins, now defaced with the militant group's black-and-white flag.

"I cried from the intensity of my grief," al-Homsi, whose name has been changed for security reasons, told International Business Times. "I have had no contact with my siblings. They are now likely to be killed or injured because of the aerial bombing."

When al-Homsi saw the Syrian regime aircraft drop dozens of bombs on the UNESCO World Heritage site this week, he immediately tried to contact his family, without success. Located in the central Syrian province of Homs, the city was a popular tourist destination until the civil war began in 2011. In May, the militant group formerly known as either ISIL or ISIS took over, and the city has since been on lockdown. Al-Homsi's brother and two sisters, as well as thousands of civilians, are still there, with many so terrified of the Syrian regime's bombing that submitting to the Islamic State group is their only option for survival.

"I do not want my siblings to stay in Palmyra. I fear the warplanes, and I'm afraid they will have to join Daesh," al-Homsi said, using the Arabic term for the Islamic State group. "Civilians in Palmyra are only afraid for the bombing of the regime. People do not like Daesh, but they see it as better than the regime."

Civilians in Syria, even those who support the opposition, know that pushing pro-regime ground forces out of a city is nearly never an easy victory. A militant or rebel gain almost always means the regime will strike with heavy revenge attacks from the air. This week, Syrian warplanes carried out the most intense attacks in Palmyra since the regime lost control of the city, with more than 90 air raids on residential areas.

"Dozens of families have fled the town and headed to Raqqa, Deir Ezzor and other areas under IS control in the Syrian desert," Rami Abdel Rahman, the head of the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights based in the U.K., told Agence France-Presse.

Those who remain in Palmyra are living without essentials, including clean water, electricity and outside contact, even with family. The Syrian regime cut off most of Palmyra's telecommunication services when it fell to the Islamic State group. Subsequent airstrikes have damaged power stations that provided electricity to residents, as well as the city's water pipes. Under the militant group's control, all satellite communication is banned with the exception of its own headquarters.

The Islamic State group usually attempts to provide some public services to civilians living under its rule, but this has yet to happen in Palmyra, according to al-Homsi. Instead of providing food and electricity, the militant group's fighters have been focused on seizing nearby towns and the neighboring Jazal oil field.

Before the 2011 uprising, al-Homsi was studying law, while relatives worked in Syria's burgeoning tourism industry. Today, his family is split between different fighting factions in Syria. He is a proud Syrian rebel, his parents tacitly worked for the Syrian regime, and his siblings could now fall into the Islamic State group's hands. After more than four years of fighting, loyalty to opposing factions is a common trait among Syrian families who have managed to maintain a semblance of normal life.

Al-Homsi's parents, like many other residents of Palmyra, lost their jobs when the Syrian Civil War began. They took the only jobs available in government-run institutions, later fleeing when the Islamic State group seized the city, fearing retaliation over their association with the regime.

Al-Homsi is now considering leaving his rebel brigade and getting a job so that he can purchase a home. He still believes the opposition will "triumph," he said, but his main mission is saving his remaining family members from the smoking ruins of Palmyra.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.