Mary Akrami, Fighting To Keep Afghan Women's Shelters Open

Gathered around a tandoori oven in the kitchen of a small Kabul restaurant, a group of Afghan women prepare naan for their lunchtime customers.

They are all survivors of domestic violence, and many will never be able to return to their families.

Mary Akrami, the founder of the shelter where they sleep and the restaurant where they work, fears these lifelines will be lost with the departure of foreign forces, who had pledged to restore women's rights in war-weary Afghanistan.

"The international community encouraged us, supported us, funded us... now they ignore us," said the 45-year-old, who is also director of the Afghan Women's Network, an alliance of NGOs.

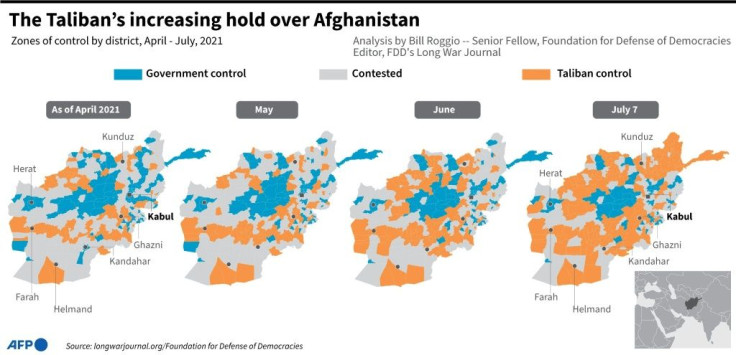

US and international troops have all but gone from Afghanistan, as the Taliban seizes control of large swathes of the country, leaving Afghan forces in crisis.

Akrami fears for her safety and that of the women at her shelters. One site has already closed because of clashes in the provinces.

"A woman who is running away from home has no place to go," she said, adding that many girls and women end up on the streets.

"We received cases of women tortured, sexually abused, physically abused," she added.

Having spent the Taliban's 1996-2001 rule in Pakistan, Akrami returned after the Islamist group was toppled by the US-led invasion.

With the help of some European NGOs in 2002, she opened Afghanistan's first shelter for women fleeing family violence.

More than 20,000 women have passed through Akrami's network of more than two dozen shelters since then.

In Afghanistan, a country of 35 million, the vast majority of women are estimated by the United Nations to have experienced physical, sexual or psychological violence, and the culture remains unforgiving to those who part with their husbands.

In some parts of the country, women are still given as brides to settle debts or feuds, and subjected to so-called "honour killings".

Since the ousting of the Taliban, which denied girls and women education and employment, there have been some hard-won gains -- women are now judges, police officials and legislators, and schools have reopened.

The government passed a law on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, although the provisions are unreliably enforced.

At the shelter in Kabul, some women study for exams or go to work, returning at night to sleep.

Others raise their children within its walls.

For those who have no opportunity to leave, Akrami has opened the restaurant.

Hassanat, who was married off as a peace offering, fled her husband when he strangled her, leaving her permanently hoarse.

The 26-year-old found her way to the capital's shelter and has since mastered cooking.

"I learned to read and I can make kebabs for 100 people. I can be independent," said Hassanat, who used a pseudonym to protect her identity.

At the restaurant, male customers are only welcome if escorted by women, flipping the conservative tradition where women have to be chaperoned to leave the house.

After pouring her life into the shelters, Akrami said she felt "betrayed" to discover Washington had failed to make any demands over women's rights in the landmark withdrawal deal with the Taliban last year.

At peace talks between the warring Afghan government and Taliban, the militants have made only vague commitments to protecting women's rights in line with Islamic values.

Meanwhile, high-profile women including media workers, judges and activists are among more than 180 people who have been assassinated since September -- killings the US and Afghan government blame on the militants.

While some activists have been able to flee the country, most ordinary women face no option but to watch the chaos unfold.

"Being a woman in Afghanistan is not easy," Akrami said.

"I'm tired of fighting continuously and I'm on the verge of losing everything," she said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.