Mind's Eye: Vision-restoring Brain Implants Spell Breakthrough

Scientists are a step closer to restoring vision for the blind, after building an implant that bypasses the eyes and allows monkeys to perceive artificially induced patterns in their brains.

The technology, developed by a team at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience (NIN), was described in the journal Science on Thursday.

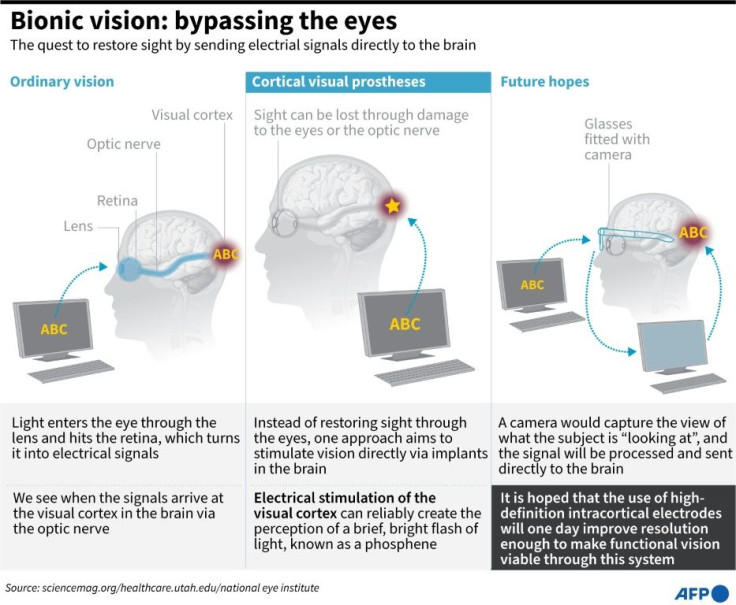

It builds on an idea first conceived decades ago: electrically stimulating the brain so it "sees" lit dots known as phosphenes, akin to pixels on a computer screen.

But the concept had never realized its full potential because of technical limitations.

A team led by NIN director Pieter Roelfsema developed implants consisting of 1,024 electrodes wired into the visual cortex of two sighted monkeys, resulting in a much higher resolution than has previously been achieved.

The visual cortex is located at the back of the brain and many of its features are common to humans and other primates.

"The number of electrodes that we have implanted in the visual cortex, and the number of artificial pixels that we can generate to produce high-resolution artificial images, is unprecedented," said Roelfsema.

This allowed the pair of monkeys to make out shapes like letters of the alphabet, lines and moving dots, which they'd previously been trained to respond to by moving their eyes in a particular direction to win a reward.

The monochrome patterns are still crude compared to real vision, but represent a major leap over previous implants, which allowed human users to only determine vague areas of light and dark.

Roelfsema likened it to a highway matrix board, and said his team now had a "proof of principle" that laid the foundation for a neuro-prosthetic device for the world's 40 million blind people.

This might consist of a camera that the user wears or a pair of glasses, which uses artificial intelligence to convert what it sees into a pattern it can send to the user's brain.

Similar technology has appeared in works of science fiction, such as the visor device worn by Geordi La Forge on "Star Trek: The Next Generation."

In a written commentary, Michael Beauchamp and Daniel Yoshor of the University of Pennsylvania hailed the breakthrough as a "technical tour de force."

The NIN team benefited from advances in miniaturization, and also devised a system to make sure their input currents were big enough to create noticeable dots, but not so great that the pixels grew too large.

They achieved this by placing some electrodes at a more advanced stage of the visual cortex, to monitor how much signal was coming through and then adjust the input.

Roelfsema said his team hopes to make similar devices for humans in about three years.

But the electrodes the team used require silicon needles that work for about a year before tissue builds up around the needles and they no longer function.

"So we want to create new types of electrodes that are better accepted by the body," he said.

Ultimately, a wireless solution would be best, as it would mean the user wouldn't need to wear an implant on the back of their skull, which requires scientists to operate and puts the user at risk of infection.

Fortunately, wireless devices that interface with the brain are advancing rapidly.

The prosthetics would only be suitable for people who once had sight and then lost it owing to disease or injury.

The brains of people who are born blind dedicate the visual cortex to other functions. But in people whose eyes stop working, the brain region remains idle, waiting for an input that never comes.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.