Mullah On The March: Pakistan Cleric Takes On Imran Khan

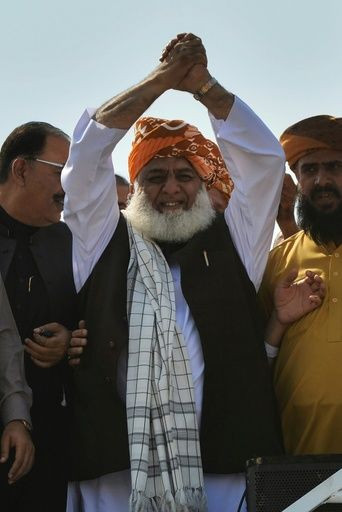

Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan faces the first major challenge to his leadership this week as a grey-bearded, orange-turbaned rival he calls "Maulana Diesel" marches to Islamabad with thousands of Islamists hoping to bring down the government.

Maulana Fazlur Rehman -- one of the country's most seasoned political operators -- has dominated the airwaves in recent days with his calls to unseat his old adversary Khan.

The prime minister, he says, did not win last year's election, but was "selected" by the powerful security establishment -- a suggestion denied by Khan, but spread widely by Pakistan's opposition since even before the July 2018 election.

"This movement will continue until the end of this government," Rehman told reporters ahead of the march.

"There is no other way... to bring Pakistan back on the democratic path."

Rehman, who heads the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI-F) -- one of the country's largest Islamist parties -- has been leading supporters from across Pakistan for days on a "Azadi (Freedom) March" towards Islamabad, with tens of thousands expected to converge on the capital.

Rehman was in Lahore Wednesday and set to arrive in Islamabad late Thursday, but so far has refused to clarify what happens next.

It is a scenario Khan himself is familiar with. As opposition leader in 2014 he organised months of mass protests in Islamabad that failed in a bid to bring down the government.

With the ability to mobilise tens of thousands of madrassa students, JUI-F protests have a history of stirring unrest, and authorities are sealing off the capital's diplomatic enclave with shipping containers.

A violent crackdown risks sparking a wider backlash in the Muslim-majority country, where mainstream politicians have long tried to keep the conservative right on side.

Bad blood

Rehman's bad blood with Khan runs deep.

Khan ran on an anti-corruption agenda in 2018 and called out "Maulana Diesel", as he dubbed him, for his alleged participation in graft involving fuel licenses.

Rehman, in turn, refers to the former World Cup-winning cricketer as "the Jew" -- citing his first marriage to Jemima Goldsmith, along with incoherent anti-Semitic conspiracies.

Rehman, a maulana (cleric) whose orange turban sports a traditional pattern from his northwest hometown, lost his parliamentary seat in 2018 to a candidate from Khan's Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) party.

Still smarting from that loss, Rehman has chosen this moment carefully.

Khan's government has been under pressure for months as anger simmers over the dire state of the economy.

Unemployment, double-digit inflation, and rising utility costs have hit ordinary Pakistanis hard -- issues other opposition parties have also railed against -- and Rehman has been eager to exploit the unhappiness during the march.

As the protest moved toward the capital this week, traders across the country launched a two-day strike, piling further pressure on Khan.

Salve for ego

The cleric insists that Khan needs to be removed from office, and a new "free and fair" election held.

But he remains vague about how he aims to achieve their goals.

That lack of substance has led some observers to suggest Rehman's protest is more a salve for his ego after the humiliating election drubbing.

"He's been left out of a game and he thinks he's been cheated out of his rightful place," said columnist Arifa Noor.

"The (economy) is more of a stick to beat the government with."

Rehman has rotated in and out of successive governments for decades, forging alliances with both Islamist and secular parties while enjoying occasional support from the military establishment.

He was once a hardline Islamist and anti-American firebrand, calling for the implementation of Shariah law publically backing the Afghan Taliban, but more recently has tried to rebrand as a moderate.

That has not stopped him from dismissing the attack on Nobel prize laureate Malala Yousafzai in 2012 as a fabricated conspiracy, and protesting the exoneration of Asia Bibi -- a Christian woman at the centre of Pakistan's most high-profile blasphemy case.

Whether the march ends in violence or not, it has undeniably thrust Rehman back into the spotlight after suggestions he was increasingly becoming irrelevant.

"When was the last time the maulana dominated the news agenda this much?" asked Noor.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.